It’s tough enough to have an economy dependent on commodity cycles, but doubly so in the small economies of Canada’s three territories, where the opening or closing of a single mine can make the difference between a growing or shrinking gross domestic product. That’s one of the lessons gleaned from the new Conference Board of Canada report, “Territorial Outlook: Economic Forecast” by Elise Martin and Marie-Christine Bernard. The report is available for purchase at

conferenceboard.ca.

According to the Conference Board’s data, the three territories are on quite different paths economically, even as the wider Canadian and U.S. economies show weak to modest growth. Noting that the “public sector will help the territorial economies over the near-term by investing in infrastructure,” the authors suggest that the financing conditions for mining will gradually improve for the territories, “mainly early in the 2020s.”

The Conference Board estimates that taken together, the three territories will see real economic growth averaging 1.8% over the 2016–2020 period on the back of the following mineral projects: De Beers and Mountain Province Diamonds’ new Gahcho Kué diamond mine in the Northwest Territories; continued development of Agnico Eagle Mines’ Meliadine and Amaruq gold projects in Nunavut; TMAC Resources’ Hope Bay gold project in Nunavut; and Goldcorp’s newly acquired Coffee gold project in the Yukon.

Of the three territories, Nunavut is best positioned to have its economy grow in the next five years, according to the report, even if its economy shrinks 2.1% as projected this year. The Conference Board expects the Nunavut economy to roar ahead by 4.9% in 2017 as metal mining makes a comeback, bolstered by infrastructure investments.

Over the long-term, the report states that “Nunavut can expect to see solid real GDP growth for the majority of the 2020s following the start of production at Meliadine.”

On the downside, mineral exploration expenses on the territory are well down from peaks achieved in the early 2010s, and the Nunavut Impact Review Board’s rejection of Sabina Gold & Silver’s Back River project has sent another chill through the mining industry when it comes to investing in early stage work.

The Northwest Territories’ economy “is on neutral this year,” the authors state, after De Beers closed its Snap Lake diamond mine in the territory in December 2015, with GDP expected to gain only 0.3% in 2016.

But with Gahcho Kué set to produce 5.3 million carats in 2017, this will “bring the economy into higher gear next year,” with 15.6% growth in real GDP, even if the “pick up in rough diamond prices is still fragile and in the early stages.”

Down the road in the 2023–2030 period, the Conference Board cautions that the territory may see “little growth” as the diamond industry matures.

And then we come to the Yukon.

To quote the authors: “Of all the provinces and territories [of Canada], Yukon’s economy is facing the bleakest near-term outlook.”

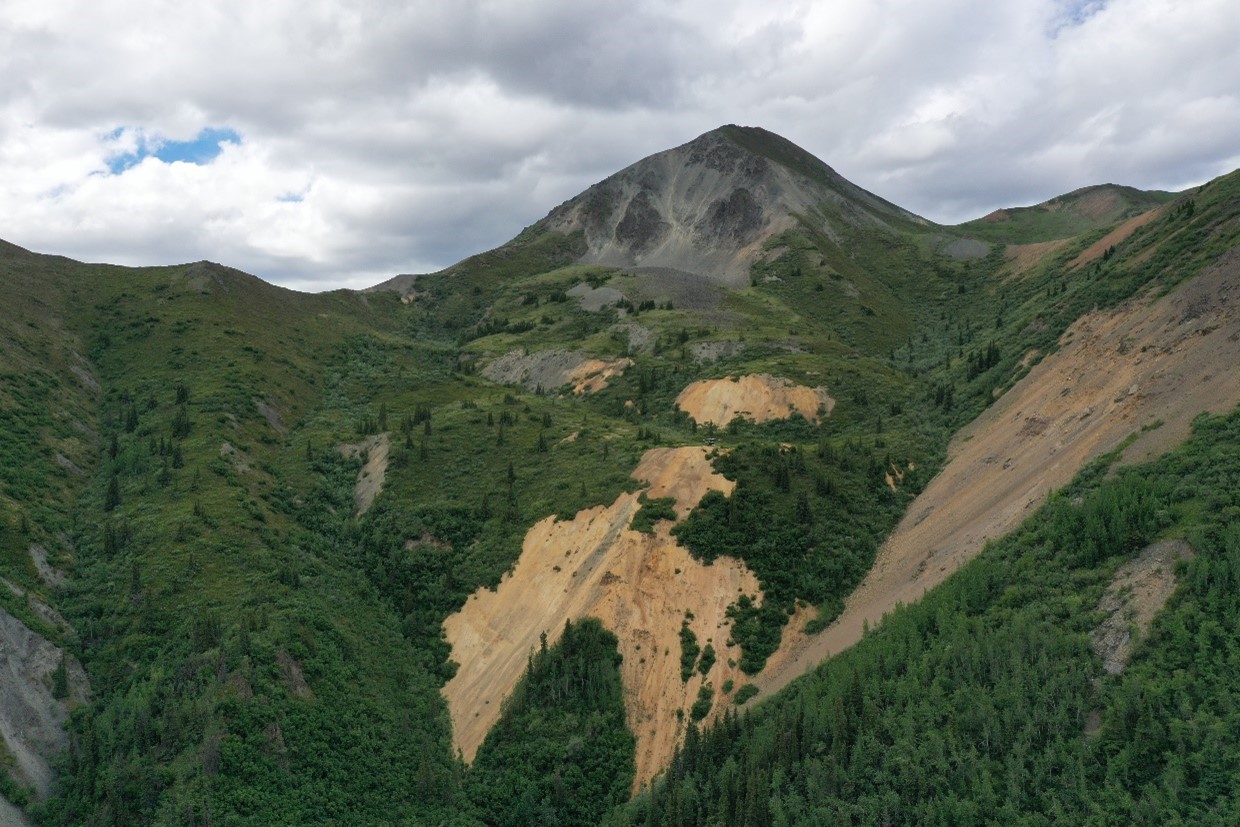

Capstone’s Minto copper mine is operating but the company has said it will stop actively mining, and process stockpiles until the mine closes, leaving the territory without a large-scale mining operation by mid-2017.

The Conference Board calculates that this will result in the territory’s GDP rising 3.6% in 2016 but contracting 7.7% in 2017, and a further 3.3% in 2018. But longer-term the picture brightens, with projects such as Coffee, Eagle and Casino in the pipeline that could help GDP grow 10% annually between 2024 and 2028.

There’s plenty more food for thought in the report, which also delves into the territories’ mixed economies, including the public sector, fisheries, construction, labour markets, education and demographics.

Comments