COMMENT: Mining industry talent forecast

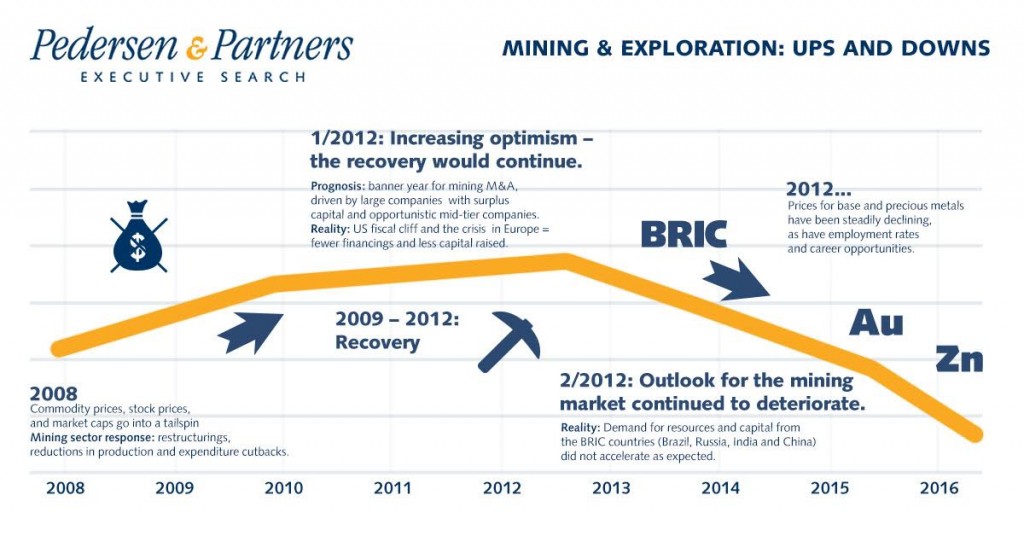

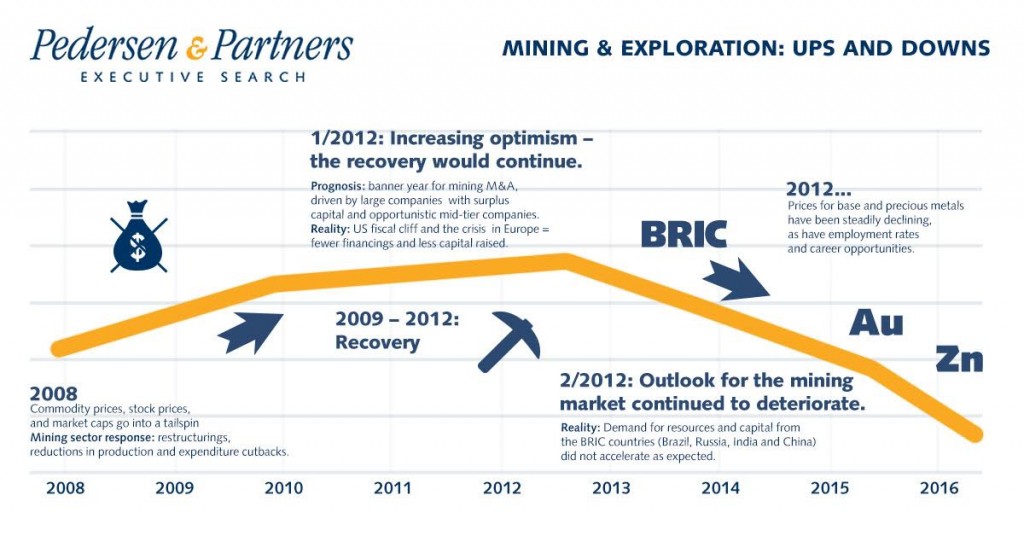

TORONTO – The cyclical nature of the mining sector means that there is frequently a gap between supply and demand for talent, […]

Many companies now think that it is relatively easy to find skilled professionals, but the shortage of technical skilled labour is still one of the most pressing concerns in the sector. For example, metallurgists are always hard to source. Many of the university programs that have been cut involved metallurgy and metallurgical engineering, and students do not necessarily choose the subject as a specialisation when it is offered within mining engineering programs. With regard to project management, there are few qualified candidates with experience handling large scale mining projects, so it is frequently necessary to complete a global search to fill this type of role. There will always be a shortage of skilled technical candidates unless we build more programs to educate them.

There is already a missing generation in the mining sector, with most employees over 50 or under 35. The rather small contingent of Generation Xers is largely due to the fact that the mining industry was going through a protracted downturn during the time when most of that group was graduating. The sector is at risk of creating the very same scenario with the youngest Millennials and the following generation failing to find positions in the mining sector.

In the last five to seven years, there has been a growth of interest in mining careers among Millennials, as they see the field as lucrative and highly technical. Unfortunately, while increasing numbers of students are entering and graduating from engineering and geological programs related to the mining industry, the industry is experiencing a growing dearth of opportunities for summer students and new graduates. The mining industry was rallying well when the current crop of students entered their programs, but as we have seen, the situation has changed drastically over the last four years. With a lack of opportunities in the sector, new graduates are increasingly seeking work in other sectors to make ends meet and entering graduate programs focused on entirely different industries.

Without a strong strategy for employee management, mining companies are facing significant challenges in terms of manpower, including the loss of senior and experienced personnel from the sector, and the prospect of a need to quickly mentor and train the younger talent during the next upturn.

The Mining Industry Human Resources Council report “Canadian Engineers for Tomorrow – Trends in Engineering Enrolment and Degrees Awarded 2009-2013” shows that across Canada, mining and minerals engineering programs are the fastest growing engineering disciplines. Enrolment has increased by 56% from fewer than 900 enrolments in 2009 to more than 1,300 in 2013. Essentially, this means that students graduating between 2011 and 2016 (and probably 2017) are or will be experiencing difficulty in procuring entry level jobs and internships within the sector.

The mining sector must work hard in a joint effort with academic institutions to address this situation before it leads to another “lost generation” in the industry. According to industry experts, one of the simplest solutions is for larger companies to offer internship programs with numbers maintained throughout the peaks and nadirs of the mining economic cycle. These programs are not costly, and they can provide new graduates with a basic level of experience in the field. This however is an option that is open mostly to larger companies and it’s also clear that students frequently take matters into their own hands by enrolling in graduate programs to try to ride out the low end of a cycle. However, a protracted downturn may mean that they come out with advanced degrees, only to find that entry level positions (for which they may even be overqualified) are still non-existent. This can also backfire on the industry, when large numbers of students opt for MBAs or other programs leading to careers in entirely different industries.

How can the industry avoid another skills shortage when the sector enters into its inevitable recovery and upswing? A concerted effort to address this issue between academic institutions, government bodies, and industry leaders is imperative to iron out the issue of recurrent talent shortages in the mining sector.

Many companies now think that it is relatively easy to find skilled professionals, but the shortage of technical skilled labour is still one of the most pressing concerns in the sector. For example, metallurgists are always hard to source. Many of the university programs that have been cut involved metallurgy and metallurgical engineering, and students do not necessarily choose the subject as a specialisation when it is offered within mining engineering programs. With regard to project management, there are few qualified candidates with experience handling large scale mining projects, so it is frequently necessary to complete a global search to fill this type of role. There will always be a shortage of skilled technical candidates unless we build more programs to educate them.

There is already a missing generation in the mining sector, with most employees over 50 or under 35. The rather small contingent of Generation Xers is largely due to the fact that the mining industry was going through a protracted downturn during the time when most of that group was graduating. The sector is at risk of creating the very same scenario with the youngest Millennials and the following generation failing to find positions in the mining sector.

In the last five to seven years, there has been a growth of interest in mining careers among Millennials, as they see the field as lucrative and highly technical. Unfortunately, while increasing numbers of students are entering and graduating from engineering and geological programs related to the mining industry, the industry is experiencing a growing dearth of opportunities for summer students and new graduates. The mining industry was rallying well when the current crop of students entered their programs, but as we have seen, the situation has changed drastically over the last four years. With a lack of opportunities in the sector, new graduates are increasingly seeking work in other sectors to make ends meet and entering graduate programs focused on entirely different industries.

Without a strong strategy for employee management, mining companies are facing significant challenges in terms of manpower, including the loss of senior and experienced personnel from the sector, and the prospect of a need to quickly mentor and train the younger talent during the next upturn.

The Mining Industry Human Resources Council report “Canadian Engineers for Tomorrow – Trends in Engineering Enrolment and Degrees Awarded 2009-2013” shows that across Canada, mining and minerals engineering programs are the fastest growing engineering disciplines. Enrolment has increased by 56% from fewer than 900 enrolments in 2009 to more than 1,300 in 2013. Essentially, this means that students graduating between 2011 and 2016 (and probably 2017) are or will be experiencing difficulty in procuring entry level jobs and internships within the sector.

The mining sector must work hard in a joint effort with academic institutions to address this situation before it leads to another “lost generation” in the industry. According to industry experts, one of the simplest solutions is for larger companies to offer internship programs with numbers maintained throughout the peaks and nadirs of the mining economic cycle. These programs are not costly, and they can provide new graduates with a basic level of experience in the field. This however is an option that is open mostly to larger companies and it’s also clear that students frequently take matters into their own hands by enrolling in graduate programs to try to ride out the low end of a cycle. However, a protracted downturn may mean that they come out with advanced degrees, only to find that entry level positions (for which they may even be overqualified) are still non-existent. This can also backfire on the industry, when large numbers of students opt for MBAs or other programs leading to careers in entirely different industries.

How can the industry avoid another skills shortage when the sector enters into its inevitable recovery and upswing? A concerted effort to address this issue between academic institutions, government bodies, and industry leaders is imperative to iron out the issue of recurrent talent shortages in the mining sector.

Comments