Canada to ban thermal coal exports by 2030

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said Canada will stop exporting thermal coal by 2030 at the latest as part of the country’s plans to support the global phase-out of the fossil fuel in favour of cleaner alternatives.

The ban would follow action already taken, including speeding out the transition from coal-fired electricity to gas and renewables, as well as putting in place investments of more than $185 million to support coal workers and their communities.

“Climate action can’t wait,” Trudeau said at COP26 summit in Glasgow, Scotland. “Since 2015, Canada has been a committed partner in the fight against climate change, and as we move to a net-zero future, we will continue to do our part to cut pollution and build a cleaner future for everyone.”

Fulfilling such promise won’t come without major challenges. Currently, the vast majority of thermal coal mined in Canada is burned domestically. Thermal coal exports, however, have increased over the past couple years and may grow further as new plants open up in parts of Asia. As a result, peak demand may result in a plateau rather than a gradual decline.

Based on figure by Ember, an independent climate and energy think tank, Canadian ports shipped between 11 million and 13 million tonnes of thermal coal between 2018 and 2020. Much of this coal was mined in the US and just exported through ports in British Columbia.

Canada produced less than 1% of global thermal coal in 2020, according to the International Energy Association (IEA). It forecasts production will shrink 0.7% by 2025, even considering the rise of coal use in Asia.

According to the IEA, global coal consumption, including both metallurgical and thermal, already peaked in 2013 and will decline as countries accelerate their shift to renewables.

But coal is experiencing a revival, particularly in the US, where natural gas production dropped last year as crashing oil prices forced shale operators to idle rigs and cut planned spending on drilling.

The jump of natural gas prices, an outcome of fewer supply, has enticed power generators to burn more cheap coal.

The upswing in coal use is expected to be short-lived. If global climate policy tightens in line with ambitions to hit net zero emissions, the IEA expects total global coal consumption to fall 55% by 2030 and 90% by 2050.

Trudeau also announced that Canada, which is among the world's biggest oil and gas producers, would move to cap and reduce pollution from the oil and gas industry to net zero by 2050.

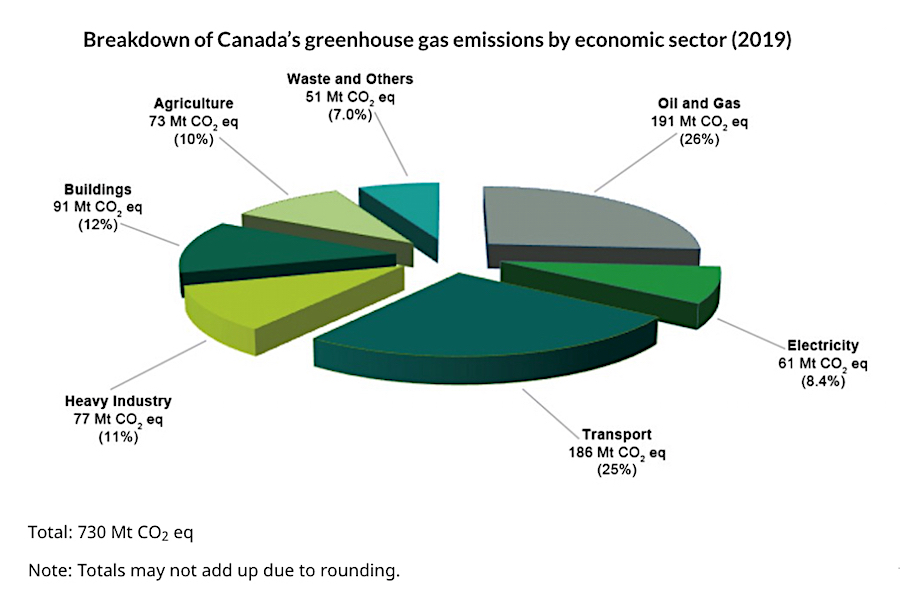

In 2019, the country's oil and gas sector accounted for 191 megatonnes of greenhouse gas emissions — 26% of the nation’s total emissions. Its second largest source of emissions is the transport sector, which generated 186 megatonnes.

Since 1990, emissions from the oil and gas industry have nearly doubled — an increase largely attributed to a dramatic expansion of the oilsands sector.

In addition, the Prime Minister asked the attending world leaders to have 60% of global greenhouse gas emissions covered by a price on pollution in 2030.

“What a strong carbon price does, when it's properly designed, is actually drive those price signals to the private sector, transform the economy and support citizens in encouraging them to make better choices," Trudeau said on Tuesday, his second and final day at the annual climate negotiations.

Canada's carbon price started in 2019 at $20 a tonne and is set to rise to $170 a tonne by 2030. The current price of $40 a tonne adds about 8.8 cents a litre to gasoline, or about $3.50 more every time a person fills a car with 40 litres.

Rebate cheques are included with tax returns to make the program revenue neutral, the government has said.

The idea is that a carbon price shouldn't leave families with less money, but provide an incentive to find ways to cut down on fossil fuel use by making it cost more.

This article first appeared on www.Mining.com.

Comments