What have you done today that did not involve a mineral?

Digging deeper: Mining a minerals’ message (Part 2)

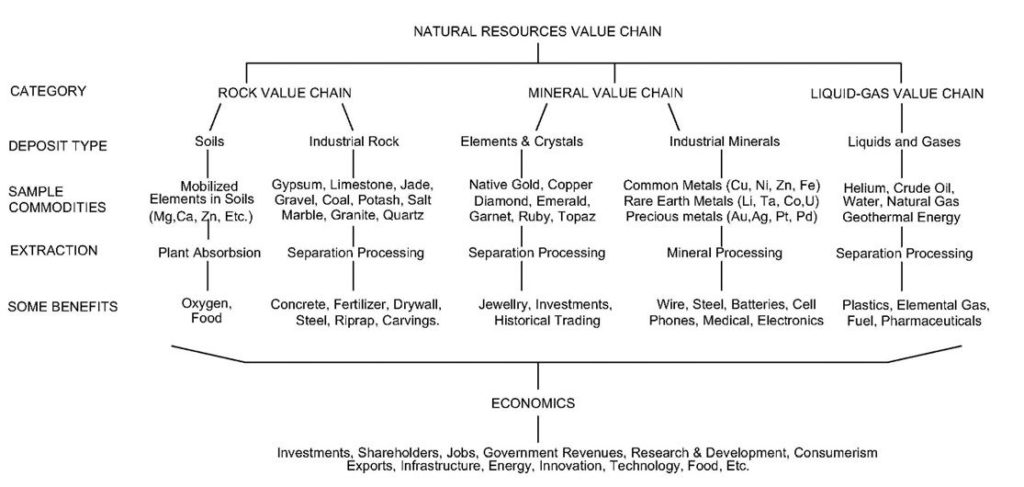

If people use any mineral in any form, that mineral holds value. In this article, we define the “natural resources value chain,” wherein natural resources can be categorized by their value as solids (including rock and minerals), liquids, or gases. Generally, all commodities require some form of industrial processing to increase their value beyond their natural state, even if it is as simple as sorting gravel by size. Humans benefit from various types of natural resource deposits.

In the “rock value chain,” mineral(s) are used in their natural rock form, directly as extracted from nature with minimal processing that maintains the material’s natural state (e.g., cutting and polishing granite for countertops, screening gravel, or carving jade). Soil is an important component in the rock value chain, as they contain mineral particles derived from the weathering of rocks. These minerals, when subject to geochemical weathering, dissolve and release elements such as calcium, magnesium, and iron, which serve as essential plant nutrients. Plants require these nutrients for growth, and in return, they absorb carbon dioxide and produce oxygen through photosynthesis. The plants help offset some of the carbon dioxide released by human processes, such as making cement from limestone.

The “mineral value chain” benefits us when nature compiles visible quantities of elements and crystals in one place (e.g., native gold and copper, diamonds, and gems) or in large enough quantities at lower grades, making industrial processes necessary for extraction, mineral processing, and refining to create final products (e.g., cell phones).

The “liquid-gas value chain” also provides valuable resources in liquid or gas form. Each link in these chains benefits different stakeholders: sellers through sales, processors through refining, and customers through the utility of the final product.

All minerals are composed of various elements from the periodic table in different proportions. Occasionally, the Earth provides pure elements, like gold nuggets or native copper, which are both minerals and metals, consisting of just one element. Some minerals, prized for their rarity and appearance, are considered precious and are used in jewelry or as investments (e.g., topaz, emerald, and sapphire). Less flashy minerals are more common and are used for industrial purposes, such as building construction. In the “mine-to-market value chain,” elements like gold or copper are extracted and refined so they can be used in manufacturing various products. Nature provides access to minerals through various deposit types, allowing a commodity like gold to hold value both in its native form and through processing of lower-grade mineral deposits.

The Canadian Minerals and Metals Plan, released by Natural Resources Canada in March 2019, has marked a significant moment in Canada’s minerals history, as evidenced by a surge in discussions on “critical minerals” in the media. However, we argue that focusing on popularity using this terminology overlooks other important minerals. Perhaps the phrases “technology minerals” or “strategic minerals” would be more representative of their need, while not diminishing the importance of other minerals. According to the document, Canada produces around 63 minerals and metals while only 34 have been identified as “critical.” While it is encouraging to see minerals gaining mainstream attention, we contend that this number is quite limiting. A more comprehensive quantification would enhance public understanding and education about the full spectrum of minerals.

Have you ever driven on the Trans-Canada Highway through Thunder Bay? It is a lovely scenic route and worth the drive. Just off the road are amethyst mines that are often overlooked when considering the “broader natural resources value chain” in Canada. These mines, like many other mineral resources, hold intrinsic value that should be recognized. Should we evaluate the mineral value chain solely in terms of “industrial” dollars? This narrow focus, particularly in overarching categories like gemstones, might contribute to why many Canadians do not fully recognize how mining impacts their daily lives. From farming and gardening to everyday use, metal tools and equipment are integral. We envision a future where everyone acknowledges the inherent value of all resources the Earth provides, whether directly or indirectly, broadly and within a given country such as Canada.

We need a definitive metric for what is considered a mineral with value. We argue that commodities should be recognized once they enter a financial transaction within an organized market. A cool looking pebble a child finds and gives to a friend has not been part of a financial transaction within an organized market. If a farmer sells field stone to a landscaper, that stone would become part of the value chain. To be considered a commodity in the economic sense, it generally needs to be part of a structured market where it is bought, sold, or traded, with transactions that are recorded and taxed. While informal transactions (like children’s trading rocks) may not involve taxes, commodities that are part of formal trade and business activities are subject to taxes and regulations. Until pet rocks start powering our devices like a battery, they might just stay outside the value chain — no taxes required!

We encourage the Canadian federal government, Mining Association of Canada (MAC), and industry stakeholders to create a readily accessible and comprehensive list of all mineral commodities produced throughout Canada’s history. While we appreciate that MAC identifies a broad range of 77 minerals in their “Facts and Figures” report (row 2 of Table 1 is based on the 2022 report), we have sought to expand the Canadian list of minerals by incorporating commodities identified within the Historical Canadian Mines HUB. This number reported by MAC is already greater than the F\federal government’s reported number of approximately 63.

In its critical minerals document, the federal government lists rare earth elements (RRE) as one critical mineral, when there are up to 17 different elements captured as RRE. The same applies to the platinum group metals (PGMs), which can be further differentiated into six different PGMs. Does this mean there are 34 or 57 critical minerals, or somewhere in between? If minerals are critical, should not they be specified by name?

We built a list using more specific geological information (Table 1), based on the commodities listed in the Canadian Historical Mines HUB (row 3 of the table). This list compiled from geologists across the country more than doubles the lists from rows 1 and 2. On the HUB’s expanded list, gemstones, RREs, and PGMs are categorized separately. Additionally, we must account for various names for construction and synonyms for certain minerals. Should items like cement and lime be on the MAC and HUB’s list, and brick be on the HUB’s list, given that they are manufactured products? We do not know. That is for debate.

We invite those working with minerals to provide information on any unique geological resources that may be missing, so we can incorporate these minerals into a comprehensive list for Canada. Then, minerals could be categorized into metallic, non-metallic, industrial, fuels, or other relevant categories. Please review both our flow chart and these lists and let us know if they are complete. With regards to the minerals list, which names should be used for duplicates, and which items should be removed? Additionally, we need to consider whether minerals that are no longer produced should be included in a historical list, while currently produced minerals should be listed as active. Minerals are like books — each one holds the potential for countless stories. By helping us build a comprehensive list of these invaluable resources, we can create an educational tool that highlights the significance of the minerals we rely on. Once this foundation is in place, the stories can truly begin to unfold.

Connections within the mining industry can expand our knowledge. Donna Beneteau is an associate professor in geological engineering at the University of Saskatchewan. Bruce Downing is a geoscientist consultant living in Langley, B.C.

Comments