What does ESG mean for the mining industry?

ESG (environmental, social, and governance) and the issues it embraces will not be new to the mining industry even though the term might be unfamiliar to some, despite ESG issues being first mentioned in the 2006 United Nation’s Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) report. At that time, 63 investment companies composed of asset owners, asset managers and service providers signed with US$6.5 trillion in assets under management (AUM) incorporating ESG issues. As of June 2019, there were 2450 signatories representing over US$80 trillion in AUM and growing, with a significant jump in AUM for ESG-centric products, particularly in the past two years of the COVID-19 pandemic. The roots of ESG go back further to the 1960s when socially responsible investing (SRI) was originally introduced because of those who were opposed to the Vietnam War.

Miners have long grappled with matters related to the “green” or sustainability agenda, but ESG now brings together all these themes in a comprehensive framework that can help a mining company or the supporters and investors in mining projects navigate and balance the benefits to the planet, people, and profit successfully.

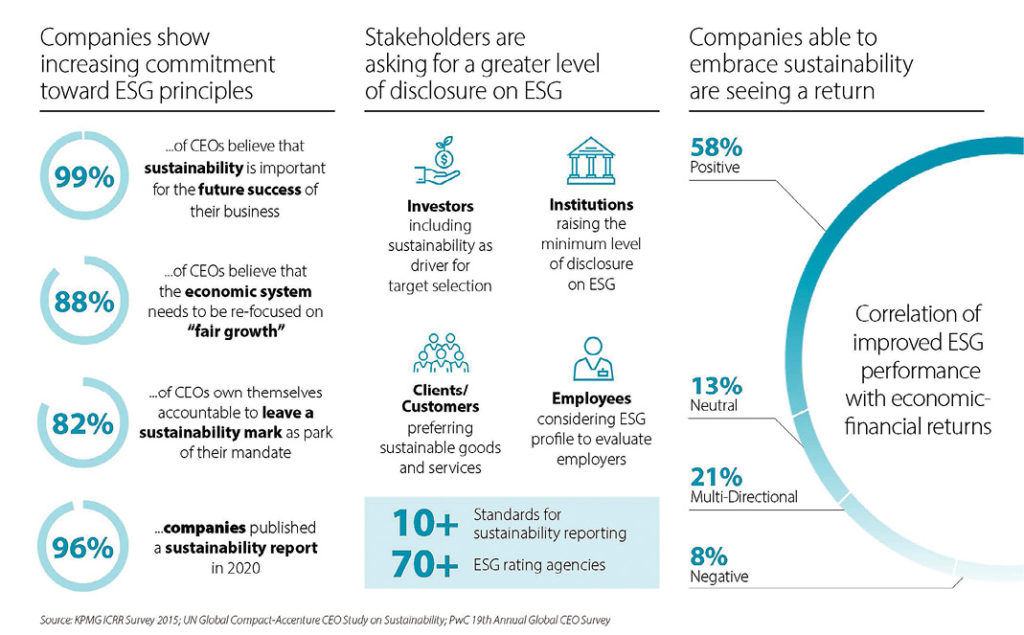

ESG initially came to the forefront primarily through socially conscious and institutional investors demanding increased attention on environmental, social and governance-related matters and data. Investors have been interested in the ESG performance of companies (not only mining companies) for some time. This focus has increased in recent years as ESG is seen as a way of mitigating risks and identifying new opportunities. This has been somewhat catalyzed because of the Covid-19 pandemic. For example, Morgan Stanley reports that there has been a 14% increase in investor interest in sustainability strategies in just the last four years. Companies looking for investment are seeing the benefit of good sustainability ratings in that they can attract more investment. In 2021, The Economist Intelligence Unit surveyed 450 institutional investors in North America, Europe and Asia-Pacific to gauge whether the ship is finally beginning to turn. “Three-quarters of investors agreed that the pandemic has accelerated their interest in ESG and, unsurprisingly, inflows into sustainable investments are expected to continue gathering pace,” stated Suni Harford president, UBS Asset Management, in a foreword to “UBS Asset Management’s Resetting the Agenda. How ESG is shaping our future.” Investments are expected to continue gathering pace in the next three to five years.

Investors are increasingly looking beyond financial statements and now want to consider the ethics, competitive advantage, and culture of a mining organization. They are increasingly integrating ESG factors when investing and proposing new standards and frameworks against which mining investments should be measured.

ESG attempts to reconcile the inescapable and inconvenient truth that mining and metals are pivotally important to our modern lives. It becomes more so as we drive the agenda of greening our lives and tackle the very real issue of global climate change and the legacy of harm done to the planet in the name of technological advances made since man first discovered that metal tools were far more effective than stone tools. Green technologies depend on industrial and rare earth elements used in batteries, turbines, and electric vehicles (EVs) to name but a few.

Modern industry relies on raw materials, so if it is not grown, it must be mined, the question remains how to undertake the task in as socially responsible and environmentally sustainable way that addresses the demands of the industry today and ensures a transition benefitting generations to come.

As technologies have advanced, we are now using a much broader suite of metals than even a few decades ago: there are now approximately 60 elements (two thirds of the periodic table) that are vital to modern society. While great advances in cleaner technologies and approaches to mining have had positive effect to minimizing harm and adding societal value in recent times, there remains a real disconnect in society about where metals come from and their intrinsic value to a greener world along the strides taken in making it a safer, cleaner and greener activity.

Against this background, it can be difficult for mining companies to navigate what is important and how it should be reported. For each mine this may vary, and a first step will always be to identify the most salient risks and opportunities. To illustrate, the following core subjects are covered by the ESG agenda for the mining industry:

> Environment: tackles questions like do we understand our exposure to climate change related transition; are we capturing all the operational improvements related to a low carbon transition; do we understand the risks or opportunities to biodiversity, ecosystem services, water, mine waste and/or tailings, air, noise, energy and make to use of a natural capital framework to enhance opportunities impacting our effects on climate change (carbon footprint, greenhouse gas), hazardous substances, or mine closure.

> Social: asks whether we have considered our risks through a human rights lens; or are we contributing to shared value and measuring our positive impacts on people and planet; and how can we improve labour and working conditions? These together impact plans to address human rights, land use, resettlement, make provision for vulnerable people, gender, labour practices, worker and/or community health and safety, and security, makes room for competing interest of artisanal miners, or address mine closure and the attendant after use potential.

> Governance: asks do we have appropriate governance, oversight and manage systems in place to tackle legal compliance, ethics, anti-bribery and corruption (ABC), and transparency; it asks whether we are exposed to supply chain risks; and challenges whether we have business ethics policies that support diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI).

Within this, mining companies need to consider whether there are environmental, social or governance risks that may affect their ability to: raise capital; obtain permits; work with communities, regulators, and NGOs; and/or protect their assets from impairments.

With reference to the destruction of the 46,000-year-old Juukan Gorge cave site in Western Australia, it is clear that this reputational, cultural and social performance disaster came about through a colossal failure of governance. It is arguably to ESG as significant a source of wake-up calls and lessons as Bre-X was to resource and reserve reporting in the 1990s and the Brumadinho tailings dam disaster was in 2019 for tailings facilities. There were hard lessons for mine companies to learn around trust and living up to their own policies and standards, rather than just falling back on doing the minimum that is legal.

ESG, with its roots founded in sustainability and corporate social responsibility, is not new and has been around for decades now. Environmental, social and governance issues seldomly fall exclusively into one bucket. They are interconnected much like a cable or intertwined rope to demonstrate with interconnectedness between the disciplines.

Fortunately, ESG solutions do not have to be complicated, but they do need to be right for a business and its objectives, and once set out and agreed with stakeholders, follow through is crucial, and it must be implemented and be auditable.

Many mining and minerals businesses are already taking active steps on their ESG agenda, identifying their priorities and measuring their performance. In our experience, the real benefits come when you move beyond measurement and take action to improve.

However, with growth in the interest in ESG, there is a growing recognition that there is a lack of accessible data to inform opinions and decisions. The need is for more data that is accessible at the right level of detail. Investors can only reward solid ESG performance if there is access to the right information to inform those assessments. It is not helped by the plethora of sustainability reporting frameworks that attempt to address the disparities.

The frameworks are many and often daunting, add to which these are voluntary frameworks that do not always ask the right questions lending themselves a risk of “green washing” performance. Fortunately, organizations like the MAC, ICMM, CRIRSCO, and others are challenging approaches and what constitutes sensible guidance and those competent to advise on issues.

No matter where one is on the ESG journey, a pragmatic business-focused approach is needed to quickly identify value and impact and develop programs that both exceed stakeholder expectations and drive quantifiable returns. This includes recognizing and unlocking the ESG value already present within an organization. Focus is on primary risks and most accessible opportunities first, then work with a company’s own team to build an ESG strategy and program tailor-made for that business.

A tiered approach works best to understanding the assets that are most critical to a business and to identify their exposure to the physical risks associated with a changing climate, for example, and where the key transition risks and opportunities lie. Then leverage technical expertise to propose practical strategies and actions to mitigate those risks, and to align reporting to the investor recognized frameworks. This will include those like the CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project) or the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and upcoming reporting requirements and best recognized voluntary frameworks like the newly launched Taskforce on Nature Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD).

David Walker is a technical director and responsible for SLR’s global mining & minerals business.

Comments