The Reefton restoration project

World-class rehabilitation in action at OceanaGold’s New Zealand site

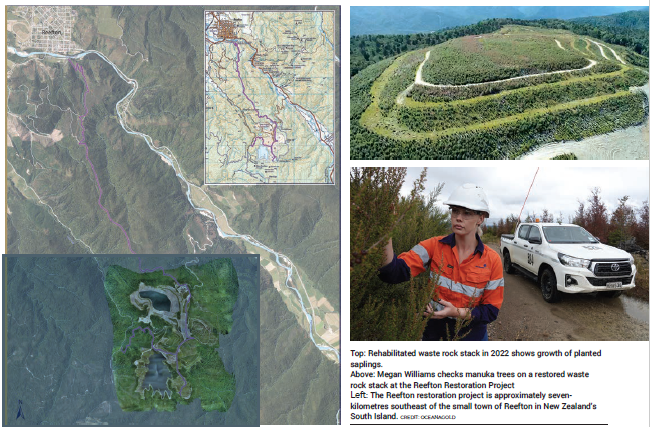

New Zealand’s South Island, OceanaGold is entering the final stages of rehabilitation of its Globe Progress mine. The mine closed in 2016, and the site subsequently became known as “the Reefton restoration project.” It is now approaching return to New Zealand’s Department of Conservation, which is expected in late 2024. Over the past eight years, OceanaGold has been progressively rehabilitating the site, using leading closure practices, and pioneering a passive water treatment system to ensure ongoing water quality for the site’s contact water.

Globe Progress mine

The modern Globe Progress mine was an open pit mine that was operated by OceanaGold for almost 10 years between 2007 and 2016. During that time, it produced 70,000 to 80,000 oz. of gold per year, totalling over 610,000 oz. over its life.

The site is situated seven-kilometres southeast of the small town of Reefton in the Victoria Forest Park, New Zealand’s largest conservation area at 1,800 km2. Reefton was home to New Zealand’s 1860’s gold rush, and as a result, it was the first town in the Southern Hemisphere to have a public supply of electricity.

The modern Globe Progress site is over 5.4 km2 in its entirety; however, only 2.6 km2 were disturbed for the mining use. The site hosts the historic Globe Progress mine (closed in 1926) in addition to the General Gordon, Empress, and Souvenir mining areas.

Closure planning

Globe Progress is the first modern large-scale gold mine in the South Island to move into closure. OceanaGold’s responsibilities under its resource consent (permitting) conditions include restoring and rehabilitating the Globe Progress site to environmental standards and conditions specified in its Access Agreement with the Department of Conservation. This includes rehabilitation of landforms, establishing plantings of native trees and shrubs, meeting water quality standards, and infrastructure removal. Megan Williams, environmental advisor at the Reefton restoration project, explains, “When OceanaGold began operating the Globe Progress mine in 2007, it was done so with the condition that the company would rehabilitate the area, re-establishing the ecosystem with native plants, after mining was completed. The goal is to leave a safe and sustainable site that we have restored as best we can with the most up-to-date technology. This means, among other things, that the trees we have planted can produce seedlings, and that the water leaving site meets all the water quality standards.”

Megan Saussey, OceanaGold’s chief sustainability officer, explains that closure was considered even before mining started at Globe Progress: “Our team looked at the entire mining life cycle and applied an elevated level of governance to planning and executing the closure of Globe Progress. We considered the environmental, social, cultural, and economic issues around closure at the initial stages of Globe Progress’ development. Through progressive closure planning, we sought to return disturbed land to a safe and stable condition, consistent with a final land use that complied with regulatory requirements and minimized our impact on the natural environment. Closure underpins the final legacy we leave in host communities and is a critical aspect in the maintenance of our promise to be a good neighbour.”

Williams agrees, “I want the work here to reflect that we did not take any shortcuts and that OceanaGold takes the environmental side of gold mining seriously. Productive mines can move into closure, and it is possible to have a mine that contributes to subsequent sustainable land use.”

Integrated reclamation in action

Concurrent restoration work, also known as parallel reclamation, was an integral part of OceanaGold’s operations throughout the working life of the mine. Williams says this has been vital to the success of the mine’s closure, “Integrated closure at Globe Progress has been a dynamic and iterative process, developed throughout the life of the mine.”

She says that earlier efforts to plant southern rata and broadleaf were discontinued because of deer browse. Deer have no natural predators in New Zealand and can damage native forests by feeding on plants, trees, and seedlings, potentially threatening ecosystems. OceanaGold now prioritizes early successional species, such as manuka and red, silver, and mountain beech.

The site’s waste rock areas have been contoured to the shape of natural landforms in the area, covered with weathered rock and topsoil and replanted. Their shape and plant cover mirror the surrounding topography, vegetation, and animal life. Tree stumps and logs help reduce erosion during rainfall events and create micro habitats.

“The woody material we have placed around the restoration area also provides little microclimates for other species we would not have planted ourselves,” says Williams. These encourage the nesting of birds, which disperse the seeds of a range of native plant species, further promoting ecological succession.

To date, approximately one million seedlings have been planted across an area of over 1.6 km2 (that is about 2.5 times the size of Disneyland). “The trees which have been planted will encourage the development of a natural forest,” Williams says. Ecosystems of indigenous tree species have been established across the site, populated by a variety of beech, and complemented by native conifers, including rimu, miro, and totara. Seeds were eco-sourced to mirror the surrounding forest and assist plant survival. “We had a four-person team each planting 900 to 1,100 seedlings a day. That is 12,000 a week, ramping up to 18,000 a week as the planting season progressed,” Williams explains.

The Globe open pit, which began naturally filling with water when mining stopped, has 0.03 km2 of native species planted on benches and roads with beech and manuka where accessible. Three hundred thousand square metres of pit wall and benches have been hydroseeded with a mixture of native grass seed and eco-sourced manuka. The small Souvenir open pit has also been rehabilitated. It was filled, capped, and planted with beech species and manuka.

To monitor the progress of the forest regeneration and the success criteria developed in collaboration with professor David Norton at the University of Canterbury and the Department of Conservation, monitoring plots were established (10 metre by 10 metre). These ensured the correct density of saplings were being planted and seedling growth was on track to maturation.

Importance of wetland areas

The establishment of a functioning wetland created within the previous tailings’ storage facility has been a highlight of the Reefton project to date, as flora and fauna have thrived.

The Fossickers tailings area was partially capped, contoured, and planted. It is now a shallow water body, known as Fossickers Lake, that has attracted waterfowl and gulls. The engineered wetland has been fully planted with around 25,000 plants, while 0.3 km2 of littoral zone, the sloped space where water meets land, has been planted with around 62,000 plants. The littoral zone is often the most fertile and complex part of a waterbody. It helps support a healthy aquatic ecosystem and beneficial organisms that serve a critical role in the foundation of the food web.

“The wetland plants have done better than we originally thought and in a shorter time frame,” explains Williams. “It has been amazing to see the return of native species to make this their home.”

Pioneering passive water treatment at Reefton

Steph Hayton, previously senior environmental advisor at the Reefton project, attributes OceanaGold’s success at Reefton to its innovative approach to closure, one that is grounded in science but pragmatic in nature. Hayton says that working on Reefton was a hugely rewarding experience. “Working on a project like this required an adaptive management style where research and trial work informed decisions on all aspects of closure. This included restoration trials determining rehabilitation methods at the beginning of the operation, all the way through to the establishment of passive treatment trials for long-term management of onsite water when we first went into closure,” Hayton added. She also says that this approach has meant innovative techniques have created some great long-term solutions.

One of those solutions was the development of a passive water treatment system to manage water quality from the site long after the site is passed back to the Department of Conservation. Water modelling results indicated that some site water would have elevated levels of certain contaminates in the long term. An options study was undertaken which identified a potential treatment system, but it was unfeasible in the area available.

Hayton started to look at Sulfate-Reducing Bioreactors (SRB) and a Vertical Flow Reactor (VFR) as part of a master’s thesis project. An SRB is an anaerobic system, which provides carbon as an energy source for bacteria to remove sulfate and other metals, from solution. A VFR is an aerobic system. Water is oxygenated prior to entering the VFR, which precipitates iron out from the water, turning it into a reddish-brown colour. Iron naturally attracts other free-floating metals in the water, forming a sediment layer which acts as a filter capturing more contaminates from the water. The concept was developed at Cardiff University and then adapted by the OceanaGold team with the help of the Verum Group and Mine Waste Management.

Hayton explains that trials using the two systems were set up at Reefton in 2018, “The trials ran over a two-year period, and it became evident that the VFR worked exceedingly well — there was a noticeable difference in the hydraulic residence times (the time it takes for the water to move through the system), when compared to the SRBs. It showed removal rates of metals were high at low-residence times, and the captured solids proved to be more stable. Our solution using the VFR removes suspended metals from the water with little running cost, using gravity flows, and no added water treatment chemicals. It has been trialled extensively, with the final design developed to exceed compliance requirements and run as passively as possible.”

At Reefton, the iron particulate gently settles on a gravel filter bed at the bottom of collection ponds. The water then continues its gravity-fed course through the gravel bed and exits the system into the nearby creek. The solids are left behind in the collection pond, then removed and stored safely in a controlled storage area. Over time, the metals will eventually be exhausted from the site’s leachable rock, and the ponds will continue to naturally spill into the creek.

Design of the VFR to full scale was required to consider topographical constraints and the integration of other site elements, such as spillways. Hayton explains that the system being the first of its kind designed to full scale made it complex; however, the installation and implementation of the system was successful, and it is operating as designed with exceptional results. “The system is removing around 98% of iron and 96% of arsenic,” she says.

Community aspects of closure

Saussey says that the community aspects of closure are just as important as getting the environmental aspects right. “From the beginning we wanted to make sure that our team worked alongside the Reefton community to make sure we listened to their views on how we could leave the site in a way that would continue to contribute to the economy of the town and the wider region,” she added.

An integral part of the Reefton project has been reinstating recreational opportunities to the site and the development of a range of visitor experiences. The company has been working with the Department of Conservation, regional councils, local Māori, and members of the community to develop access and activities that are both safe and sustainable in the long term.

A multidisciplinary working group was formed in 2021 with OceanaGold, the Department of Conservation, local Māori representatives, and the local community board to work on practical options. Linkages to existing hiking trails and the provision of a 12-kilometre multi-purpose trail making it possible to access the site from Reefton town by mountain bike are currently being constructed. Lookouts and rest areas, and interpretive panels detailing the social, cultural, and technological history of the area have been developed and will soon be installed, replacing the area previously occupied by the mine process plant.

Saussey says that the goal is to establish a sustainable visitor opportunity to benefit the Reefton community at the Globe Progress mine site which aligns with the obligations in the company’s Access Arrangement.

Handover to the Department of Conservation is planned for the end of 2024 by which time the site will be ready to cater for the visiting public as part of the Globe Progress Visitor Experience Project.

Comments