The mines across the tickle: Newfoundland’s Bell Island

When I first moved to St. John’s, I heard about Bell Island almost every morning on the radio. If the traffic report said the ferry is moving well on the tickle (a narrow straight in Newfoundland English), that meant commuters to and from what is essentially a bedroom community for the nearby provincial capital had escaped the common delays of rough seas, bad weather, or mechanical breakdown — at least for one day. Eventually, I took my two boys out to Bell Island as they got a bit older, but not so old they would not find the ferry ride a big adventure. Bell Island is not a big place (about 34 km2), but between picking wild cranberries, eating the best fish and chips in the St. John’s area (at Dicks’, right by the ferry terminal), and hanging out at the lighthouse, there was no shortage of things to do.

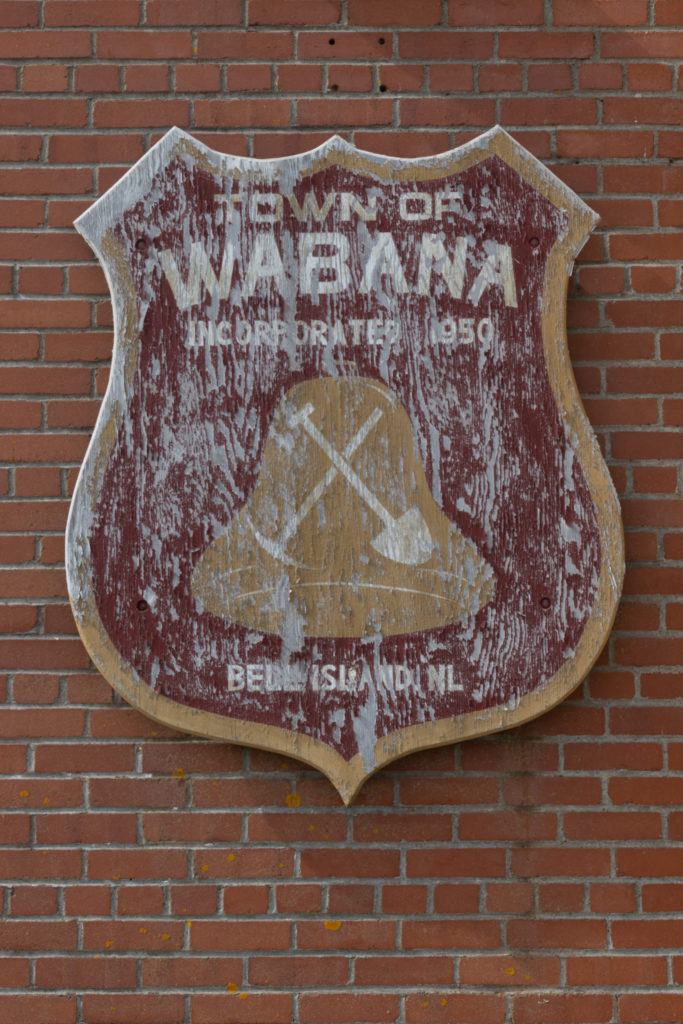

One of the biggest thrills of all was visiting the “No. 2 Mine Tour and Museum” near the main town of Wabana. Here, we learned that the mine had begun in 1895 as a small open pit (surface) iron operation, but an American industrialist, Henry Melville Whitney, purchased some of the Bell Island holdings in 1899 as a source of iron for his new Dominion Iron and Steel Company steel mill in Sydney, Nova Scotia (the remainder of the Bell Island claims were owned by the Scotia Company, who operated a smaller steel mill in Sydney). By 1902, Dominion Iron and Steel and Scotia had depleted the surface deposits at Bell Island and began to push tunnels out under the sea, using room and pillar mining to extract the iron ore. Before the mine closed in 1966, miners had produced nearly 80 million tonnes of ore, 25% of the iron used in Canadian steel production while the mines remained open. The Bell Island mines had doubled its annual ore production between 1935 and 1965, peaking at nearly two million long tonnes of ore annually, but the surface mines of the newly developed Labrador and Quebec iron mining complex were cheaper to operate than the complex sub-seabed mines of Bell Island and yielded a higher-grade ore. The last of the Bell Island mines (No. 3) closed in 1966. The island’s population dwindled from 12,000 to roughly 2,000 people today. As if to drive home this point, at the end of our tour the guide whirled a light toward the end of a tunnel, revealing how seawater had reclaimed much of the former mine.

A mine is always much more than the ore it produces, and Bell Island seems to have more than its fair share of colourful characters. In her popular book, “The Miners of Wabana,” local historian Gail Weir documented the quirky beliefs and habits of the Bell Island miners. Some, for instance, invoked taboos against calling on men who had slept through their shift because it meant certain death for the latecomer. Experienced miners often played pranks on the newbies, sending them to the shop for a fictitious “skyhook” or asking them to fill a wheelbarrow with smoke. Folk beliefs permeated the cultural life of the mines. Miners and their family members often claimed they had seen the ghosts of those killed in accidents, chilling late-night sightings of miners underground or on the surface who left no footprints. Others claimed to have seen, and even spent time with, diminutive faeries, encountering them in the mine and on the surface. Perhaps more tangibly, miners also maintained close relationships with animals, caring for the horses that worked in the mines and sometimes adopting individual rats that lived underground as pets. Of course, work at the Bell Island mines was primarily devoted to drilling, blasting, mucking, and hauling, the same as miners anywhere else in the world. But Weir’s account of Bell Island is a good reminder of the unique cultural practices that may develop in tandem with a mine.

Bell Island is also exceptional as one of the few places in North America to come under direct German attack during World War Two. Newfoundlanders were aware of the threat from German U-Boats, as news of torpedo attacks on North Atlantic shipping convoys featured prominently in local newspapers. In March 1942, three explosions rocked the south side of St. John’s Harbour as a German submarine bounced torpedoes harmlessly off the rock. But on September 5, 1942, Bell Island iron ore became a target as the submarine U-513 followed a coal boat into Conception Bay and settled on the ocean floor at 20 metres depth close to the ore carrier loading docks. The next day, U-513 sank two ore carriers, the SS Lord Strathcona and the and the SS Saganaga, killing 29 crew members. Although military censors kept news of the attack out of the press, word of mouth accounts of the tragedy spread, and Canadian navy commanders beefed up anti-submarine patrols around Bell Island.

Even so, another attack occurred on November 2, 1942, as U-518 arrived with the explicit mission of attacking iron ore carriers headed for Sydney. Weir interviewed one Bell Island resident, Joe Pynn, who claimed he saw the submarine in the days leading up to the attack and tried to warn the Canadian navy, but nobody believed him. The U-boat aimed its first torpedo at the SS Anna T., but missed, hitting the pier, resulting in a loud explosion that alerted Bell Islanders to the attack. U-518 then sunk the SS Rose Castle, killing 28 crew, and then a Free French ship from North Africa, PLM 27, killing 12 crew. These two attacks compounded other tragedies that had occurred that fall, most notably the sinking of the Caribou on October 14, a passenger ferry on route from Sydney to Port-aux-Basque, with 167 people lost at sea. At Bell Island, the Canadian Navy managed to prevent further U-boat attacks by installing protective steel netting around the pier, but the heavy toll of U-boat attacks had brought the war home to Newfoundlanders in a terrible way.

As with so many places where a mine has shut down, Bell Island has harnessed its mining history to re-brand itself as a tourist destination. In addition to the mine tour, the No. 2 Museum displays a collection of remarkable photographs by famous photographer Yousuf Karsh, who visited Bell Island in 1953 to document the working life of the miners for Maclean’s Magazine. In 1990, a group of Wabana residents organized a mural project to commemorate the town’s mining heritage and attract visitors. Scuba diving tours of the shipwrecks are popular, while in 2016 the Royal Canadian Geographic Society funded a diving expedition into the old mining tunnels. From 1997 to 1999, a theatre group produced a play, “Place of First Light: The Bell Island Experience,” based on the lives of historical figures who worked in the mines. In 1988, the Canadian government designated the mine workings of Bell Island as a site of national historical significance, recognizing its contribution to the Atlantic steel industry and its status as Newfoundland’s most important mine.

John Sandlos is a professor in the History Department at Memorial University of Newfoundland and the co-author (with Arn Keeling) of “Mining Country: A History of Canada’s Mines and Miners,” published by James Lorimer and Co. in 2021. His new book, “The Price of Gold: Mining, Pollution and Resistance in Yellowknife” (also co-authored by Arn Keeling), will be released with McGill-Queen’s University Press in 2025.

3 Comments

Gar

I believe it freshwater in the mine. I did the tour a while back. The tour guide told us it was fresh water we were seeing

Dianne

Very enlightening history. I was trying to send the link to others but couldn’t see a share. Tks so much for posting this article. Is Gail Weir’s book ? Tks Dianne

Heather Chafe

Thank you for sharing your experience and history of Bell Island. We look forward to seeing you again in the future.