Sparking up the Ring of Fire

Noront Resources’ camp. Credit: Noront Resources

Once there were many. Now there are just two. The discovery in 2008 of vast deposits of nickel, copper, chromite, platinum and palladium in the Ring of Fire, in Ontario’s remote Far North, fuelled dreams of fabulous wealth and unleashed a predictable stampede to stake claims.

More than 35 junior mining companies laid claim to a piece of this crescent-shaped, mineral-rich formation, which, by some estimates, spans 5,000 sq. km. Even once mighty Cliffs Natural Resources of Cleveland jumped in with grand plans to invest $3.3 billion to a build a mine, a processing facility and a transportation corridor of 300-plus km to the CN rail line at Nakina.

But Cliffs was later forced to file for bankruptcy protection. Exploration money dried up. The dreams of future wealth evaporated as the prospects of production receded ever further into the future. And one by one, all those juniors exited, leaving just two Toronto-based companies still standing – Noront Resources and KWG Resources.

“We looked at this strategically,” says Noront president and chief executive officer Allan Coutts. “We thought we could buy everyone out for pennies on the dollar and that’s what we did. We’ve got about 26 deposits under our flag. Nine of them have 43-101 resource-compliant files and two have had full feasibilities completed.”

The Eagle’s Nest nickel, copper, platinum and palladium project is one of those two and the most advanced in the Noront portfolio. Coutts says the company plans to ship nickel concentrate that resembles moist, black beach sand to smelters in Sudbury for further processing. Crushed chromite ore will be shipped to a ferrochrome smelter, which the company hopes to build in Sault Ste. Marie, and the ferrochrome will be shipped to customers in the U.S.

Noront’s fortunes took a big turn for the better last December when Wyloo Metals, one of Australia’s largest private investment groups, bought the debt and equity previously held by Resource Capital Funds, giving it a 23% stake in the company.

“They love the exploration upside,” said Coutts in late April. “They’re willing to be there the whole way, including financing mine development.”

Indeed, Wyloo liked the upside so much that at presstime in May, it had just announced its intent to make an offer to acquire Noront for $133 million. In response, Noront noted that Wyloo hadn’t actually made an offer yet and recommended shareholders hold tight until there was an offer to consider.

KWG’s stake in the region is narrower, but also promising. The junior, which has a market cap of under $20 million, holds a 30% interest in Noront’s Big Daddy chromite deposit and 50% of the Black Horse chromite deposit. It is that strategically important mineral that excites the dreams of KWG president and chief executive officer Frank Smeenk.

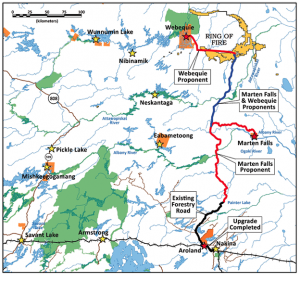

Map of proposed road development and communities in the Ring of Fire. Credit: Noront Resources

Chromite, he notes, is an essential component of stainless steel and demand for that product is growing by 7-8% annually. Currently, though, most of the world’s chromite is produced in a handful of countries – South Africa, Zimbabwe, Turkey, Pakistan and Iran, among others. That means North American and European steel makers must compete for supply with China.

“The Western Hemisphere, with one small exception in Brazil, has never had a source of chromite until we discovered, in the Ring of Fire, the most humungous orebody of its kind in recorded history,” says Smeenk. “This thing is 14 kilometres long and 130 metres wide and we’ve only scratched the surface with the little drilling we’ve done.”

The Ring of Fire holds vast potential to generate wealth for investors and tax revenues for governments, as well as badly needed jobs and economic development for many impoverished First Nation communities in the province’s Far North, but several major hurdles must be surmounted before any mining takes place.

A transportation corridor must be built across an inhospitable terrain of peat bogs and swamps, traversed by dozens of rivers and lesser waterways. Then there is the growing coalition of environmental groups and individuals demanding a moratorium on all development until a whole host of conditions are met. In addition, concerned about potential impacts on regional wetlands and watersheds several First Nations are opposed, including Neskantaga, located southeast of the Ring of Fire, and Attawapiskat, Kashechewan and Fort Albany, which are located hundreds of kilometres east of the Ring on the James Bay coast. Finally, federal and provincial environmental assessments must be completed before any permits are issued.

Greg Rickford, Ontario Ministry of Energy, Mines, Northern Development and Indigenous Affairs

Infrastructure plans

KWG is pushing a rail corridor that extends from Nakina some 330 km north to McFaulds Lake where the first mines would likely be developed. The company is studying an innovative system developed by Sudbury, Ont.-based Rail-Veyor Technologies Global. The Rail-Veyor system is electrically powered, fully autonomous and moves ore along light rail tracks in cars that are 30 to 48 inches wide and form a continuous U-shaped trough.

However, Ontario’s Minister of Energy, Mines, Northern Development and Indigenous Affairs Greg Rickford says that any transportation corridor must be more than just a conduit for moving minerals to world markets. He sees it as a “corridor to prosperity” for the remote First Nations living in the Far North.

“This is not about building a road to get a mine,” Rickford says. “This is about building a network of roads so that Indigenous communities have better access to health, social services, broadband and a clean alternative to diesel-generated electricity.”

To that end, the government has provided $50 million funding for First Nations-led environmental assessments for two sections of road. Marten Falls First Nation has retained Aecon Group to conduct the assessment of a 200-km southern segment that would run from Aroland to Ogoki. Webequie First Nation, the closest Indigenous community to the Ring of Fire, is leading the assessment of a 160-km road that would link the community to any future mines and the band has hired SNC Lavalin.

These two stretches would form part of an eventual Northern Road Link, but there remains a gap of some 200 km between Ogoki and Webequie. “There have been some preliminary discussions and interest shown by world class infrastructure companies to partner with Indigenous communities on the development of that corridor,” Rickford says.

However, Rickford says such a project must await the outcome of provincial environmental reviews as well as a regional assessment under the auspices of the federal government’s newly formed Impact Assessment Agency.

Calls for Indigenous-led regional assessment

Environmental groups, allied with First Nations demanding a moratorium on development, are clamoring for a review that considers a broad array of impacts on Indigenous communities close by and far removed from any future mines.

A coalition of three First Nations, Attawapiskat, Fort Albany and Neskantaga, insists that the regional assessment must be an equal partnership between the federal government, Ontario and an “Indigenous governing body,” although the composition of such a body is far from settled. The coalition also insists that the terms of reference must be set in collaboration with the First Nations and that the assessment must be Indigenous-led.

“This moratorium will be enforced by our First Nations, our Mother Earth and our lawyers in Canadian courts,” according to a joint statement released by the coalition in early April. “The risks are too great to allow the Crown to steamroll over our Mother Earth, our rights and our future.”

In short, the path to production in the Ring of Fire will be long and arduous, but Chris Hodgson, president of the Ontario Mining Association, believes that both Indigenous communities and environmentalists can be persuaded of the net benefits.

Mining brings jobs, service contracts and economic development to remote, isolated and often impoverished First Nations. “Ontario mining companies employ more Indigenous Canadians than any other sector of the economy,” says Hodgson, adding that 11.2% of the industry’s workforce is Indigenous.

As for climate, the Ring of Fire hosts several minerals critical for the transition to a green economy. “Even ardent environmentalists are looking at the role mining plays in the greening of the world,” says Hodgson. “Smart people who care about climate change realize we need more minerals coming from jurisdictions like Canada.”

Comments

Bruce

Perhaps someone should talk to Elon Musk. Cut the red tape out of the equation….worlds best planner on mega projects, environmentalist and is bad need of nickel. You might be surprised he may build a tunnel instead of an above ground railroad.