Restoration: Harnessing technology to improve revegetation outcomes

By 2030, it will be necessary to revegetate at least one billion hectares of land worldwide to reach the United Nation’s sustainable development goals. Canada has set an ambitious goal to conserve and revegetate 30% of the country’s land mass by 2030. As global leaders in sustainable resource development, the Canadian mining sector has a unique opportunity to contribute to these shared goals.

The goal of revegetation is to recreate a functional and diverse ecosystem that resembles the original pre-industrial conditions as closely as possible. Plant communities can be established through sowing seed, planting seedlings, or allowing the area to be recolonized slowly over time. Planting seedlings is often impractical for larger sites due to the higher cost of plant materials, labour, and shipping. Allowing areas to recolonize naturally can be prohibitively slow, is often not in-line with compliance requirements, can inadvertently give invasive species an opportunity to dominate open sites, and may simply not be successful in sites with a long history of industrial use. Sowing native seed, termed seed-based restoration, is often the only practical option for revegetation of larger sites. Seed-based restoration refers to the practice of sowing seed of varieties native or endemic to an area with the goal of recreating a functional and diverse ecosystem that resembles the original pre-industrial conditions.

Although nine out of 10 revegetation projects in Canada utilize non-native grass seed mixtures, the benefits of employing native species are undeniable.

- Native plants have adapted to their local conditions over thousands of years and have the best chance of long-term survival, especially on challenging sites.

- Native plant species help to increase biodiversity as insects, small mammals, and birds all have a relationship with native plants. They rely on them for food and shelter, and many require the presence of one or a handful of native plants for survival.

- A site revegetated with natives can act as a seed bank assisting in the colonization and increasing the biodiversity of surrounding sites.

- Many native grasses have been shown to help ward off the spread of invasive plant species, which is especially relevant for degraded sites which are more susceptible to invasives.

- The deep and fibrous roots of native grasses, wildflowers, and shrubs are the best natural tool against soil erosion and sedimentation.

- Native plants, with their robust root networks, can remove pollutants from the soil before they reach larger water bodies.

- Native grasslands are excellent carbon sinks and can sequester an average of 100 tonnes of carbon per acre.

It is encouraging to see a trend towards native seeds being increasingly prescribed as part of mining, construction, landscaping, and restoration projects. Unfortunately, low seedling germination rates, especially on sites with a long history of industrial use, present a major challenge for restoration practitioners. The typical conditions of mining or industrial sites are inhospitable to seed survival. These sites are often characterized by acidic or basic conditions, low or absent organic matter, a soil layer that lacks nursery species and compacted soil, high soil erosion, and hot and dry microclimates at the soil layer. Fortunately, there are several technologies that can help to increase germination success, especially on difficult sites. One such technology is the process of seed enhancement, which involves using innovative techniques and products to maximize germination rates and seedling survival.

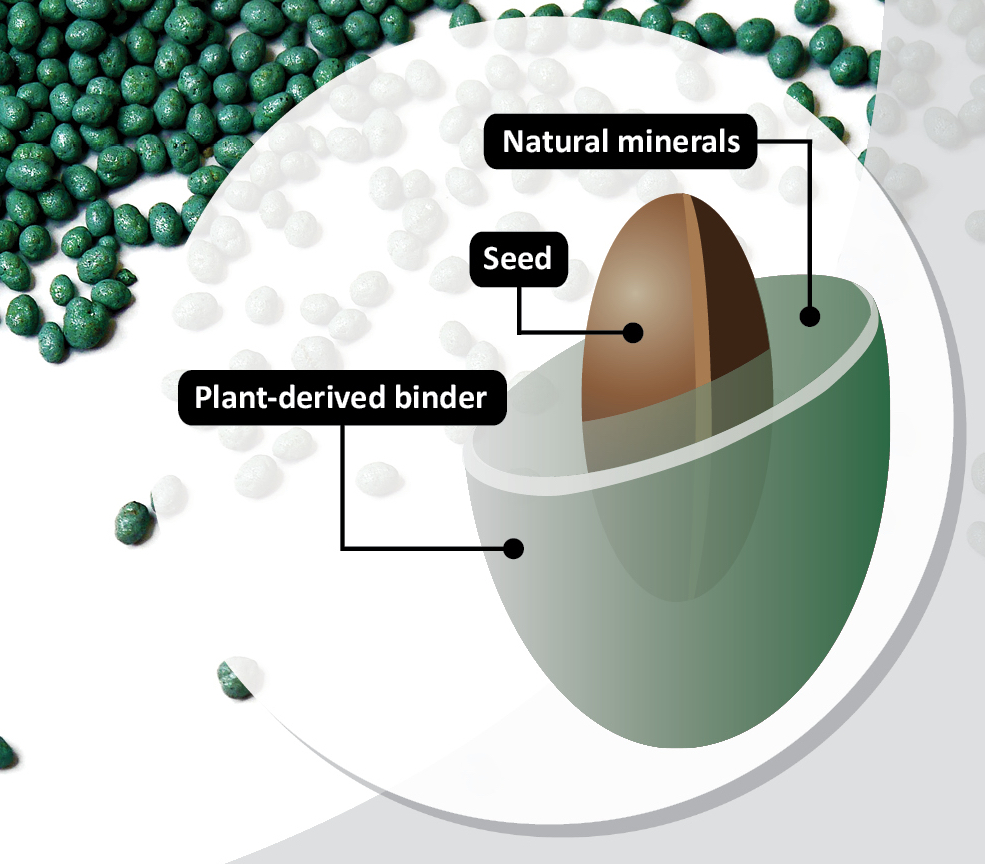

Seed coating is a type of seed enhancement that holds a lot of promise for the restoration sector. Seed coating, in its simplest form, is the process of applying additional materials to the surface of the natural seed coat. This practice can be used to modify the physical properties of seed and/or for the delivery of active ingredients. Seed coating is administered to increase germination, survival, and make application easier. Coating seeds has also been shown to decrease predation, as the coating serves to confuse predators as the seed no longer looks or smells like a seed. The physical modification of seed aims to improve seed handling and flowability when seed is broadcasted by standardizing seed weight and size. In the case of many native species which often have small, high-value, difficult to source, or morphologically uneven seeds, seed coating is particularly advantageous.

Credit: Dwight Chorney (Erocon Environmental Group, Gogama, Ont.)

Seed enhancements have gotten a bit of a bad reputation due to the public’s association of seed technology with large agrochemical companies and the assumption that coatings will contain chemicals that are harmful to the environment. Although this can be the case for many of the more conventional coatings on the market, which are applied to commercial seed crops like cereals, corn, pulses, and soy, this was not traditionally how seed coatings were used. In fact, for over 100 years, farmers have been coating their own seed to increase yields and shelf-life and improve handling, using natural minerals like clay or lime.

The restoration community is taking a different, more mindful trajectory, in its use of seed enhancements. In this space, both industry and the international research community are creating seed enhancements that are environmentally minded and specifically tailored for application in habitat restoration. One such example is the completely biodegradable, environmentally friendly, and microplastic free proprietary seed coating recipes that were developed for the restoration sector at Northern Wildflowers (Sudbury, Ont.). The standard recipe utilizes a mixture of seven natural minerals and a plant-based binder, making it completely natural and safe for the environment. The coating is designed to have a tough outer coating, which will withstand the mechanical force of broadcasting. However, once the seed is sown, the coating will quickly dissolve during a rain event, leaving behind a pocket of rich natural minerals that will support germination.

There are several naturally derived products that can be used to coat seeds to ensure better survival, these can include simple products like chilli pepper powder, lime, various minerals, nutrients, and natural fungicides. Several more sophisticated, natural products can also be applied to seed coatings. Natural plant hormones like gibberellic acid (GA3) can be incorporated to trigger germination or promote faster growth, or the plant hormone kinetin can be applied to help increase seed emergence in high salt environments. Other examples include the application of natural acids to break down tough seed coats, or the application of alginate, which is derived from seaweed and acts a hydrogel, attracting and absorbing water, thereby increasing seedling success in dry environments.

A specific seed coating recipe of minerals and compounds can be developed to address the unique challenges of a specific site and project. For example, a client might be looking to seed on a five-hectare orphaned mine site in northern Saskatchewan. The site has challenging conditions with high winds, acidic soil and due to project constraints, the client is seeding in the spring. Additionally, although spring seeding is common, fall is the ideal time to sow native seed. Most native species have seed with a built-in dormancy mechanism that prevents them from germinating until the winter has passed. This means most seed sown in the spring will remain dormant until the following spring, making them susceptible to predation, disease, erosion, and rot in the meantime, which further reduces germination success. For this project, a customized seed coating recipe can be developed to optimize success on site. The coating recipe might include the following:

- lime, which is a natural mineral with the ability to buffer acidic conditions;

- gibberellic acid, which is a natural plant growth hormone that will encourage seeds to break dormancy and germinate soon after spring application;

- and a thick, heavy encrusting layer of natural minerals which will make the seed heavier, making them less likely to be blown away, which will also increase the ease of handling and broadcasting.

Credit: Chase Beaudoin (Northern Wildflowers, Sudbury, Ont.)

A seed second coating technique termed conglomeration can also be applied to small seeds, where several seeds are formed into a larger ball, which is held together by a binder and clay. The group of seed “conglomerated” together actually have been shown to have higher germination rates compared to smaller seeds germinated individually. Tiny seeds often struggle to germinate against the crusty layer that can form on dry or degraded soil. Conglomeration is particularly beneficial when applied to native goldenrods, and asters, which are key restoration species but are challenging to establish due to their tiny seed and naturally low germination rates.

There is a remarkable opportunity

for the Canadian mining sector to

actively participate and lead in sustainability efforts.

In conclusion, Canada and the world have embarked on an ambitious journey towards revegetation, recognizing the crucial role of restoring and preserving our natural ecosystems. This presents a remarkable opportunity for the Canadian mining sector to actively participate and lead in sustainability efforts. Fortunately, there are numerous promising seed technologies available that can simplify and enhance the revegetation process. By embracing seed-based restoration and leveraging these advancements, the Canadian mining sector can display its commitment to environmental stewardship and fulfill its social responsibilities, while simultaneously fostering a greener and more sustainable future for all.

Jenny Fortier is a biologist with over 15 years of experience in habitat restoration and is the founder and CEO of Northern Wildflowers Inc., a native seed grower and supplier based in Sudbury, Ont.

Comments