Remembering the Hillcrest mining disaster

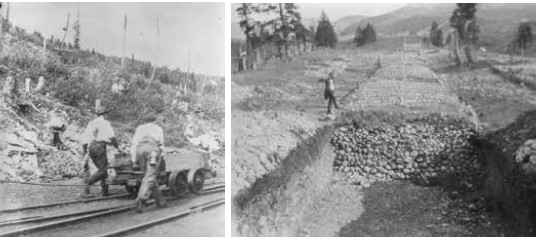

Underground coal mining has been synonymous with danger for much of its history. While coal miners faced dangers found in all underground mines (falling rock, collapsing stopes, or a tumble down a shaft), the chemical makeup of coal presented its own unique perils. Chief among these is the fact that coal seams emit highly flammable methane (often called firedamp) that could be ignited from improperly placed explosives, a faulty gas lamp, or even a small spark from an electrical wire. Coal dust is flammable too, and though it was much harder to ignite than methane, even a small gas explosion might detonate dust in the air or clinging to walls and timbers. Miners fortunate enough to avoid an underground explosion still faced grave danger from the dreaded afterdamp, a mix of carbon monoxide and other toxic gases that typically spread far and wide in the mine after an explosion.

Colliery explosions were especially common in the 19th and early 20th century, when coal was mined at a furious pace to meet the energy demands of industrial expansion in Europe and North America. Canada’s coal producing regions remained small by global standards, so the number of fatalities never reached the shocking total of 3,242 miners killed in just one year (1907) in the United States. Even so, 2,584 miners died in Nova Scotia between 1838 and 1992, the vast majority in coal mines; while in Alberta, 773 miners died between 1906 and 1930, most of these in the burgeoning coal mining regions at Lethbridge and in the Crowsnest Pass. Major coal mining explosions occurred at Nanaimo, B.C., in 1887 (150 dead); Springhill, N.S., in 1891 (125 dead); and Coal Creek, B.C., (128 dead). But the worst of all Canada’s coal disasters occurred at the Hillcrest mine on the Alberta side of the Crowsnest Pass.

On the morning of June 19, 1914, the morning shift of miners entered the Hillcrest mine, which had just re-opened after low seasonal demand for coal had shuttered the mine for two days. At about 9:30 a.m., a powerful explosion ripped through section number 2 of the mine, causing parts of the mine to cave in and afterdamp to spread throughout its inner workings. The mine’s general manager, John Brown, rushed to re-start a fan at the section’s entrance, pushing oxygen back into the mine, saving at least some lives. Tragically, however, there were not that many lives left to save. Of the 237 men working in the mine, only 48 escaped alive. Rescue efforts were complicated by the total collapse of one of the mine’s two entrances, and impromptu rescue teams had to pick away rubble at the other entrance to gain access to the underground. These initial rescuers had no protective equipment, and three had to be brought back to the surface because of exposure to the afterdamp. By the afternoon, rescuers from other coal communities came equipped with gas masks that enabled a more thorough search of the mine. For the most part, they found only the bodies of the dead, eventually bringing all but three of the 189 deceased miners to the surface.

In the days that followed, newspapers reported a scene of crippling grief among Hillcrest mining families. The District Ledger of the United Mineworkers noted the “many sorrowing and tear-stained faces” in the community, and other press outlets reported on the overwhelming sorrow in the miner’s hall as rescue crews laid out the dead for identification and burial preparations. The Winnipeg Free Press described multiple stories of tragedy: the death of David Murray and two of his sons had left ten surviving children without a father; a restaurant owner, Mrs. Petrie, lost all three of her sons; Charles Murray had bravely and recklessly run into the mine to search for his two boys, but none of them came out alive; superintendent Thomas Corkill died on his last day at work, never realizing his dream to move to property he owned near Nelson, B.C.

In the aftermath of the disaster, there were widespread calls for a public inquiry (including The Canadian Mining Journal’s appeal for a “rigorous” investigation in its July 1st issue). A commission of inquiry, led by Judge Arthur A. Carpenter, began hearing evidence on July 2nd. Almost immediately, Carpenter ruled out some potential sources of ignition, noting that open flame lamps were prohibited in the mine and the employee responsible for firing explosives had not yet set up blasting equipment on the morning of the explosion. On the crucial question of explosive gas, however, Carpenter had difficulty reconstructing air flows in the mine because the only two employees who understood the ventilation system had been killed and the ventilation plan destroyed. One miner suggested that air being expelled from the mine often mixed with incoming air, compromising the system’s ability to remove underground gases. Carpenter was bewildered by the testimony of William Adler, the examiner responsible for monitoring underground gas, who claimed that some areas were “full of gas” but later testified that there was no “undue amount of gas” in the mine. The evidence on dust was contradictory as well: some witnesses testified that coal dust was everywhere in the mine while others suggested it was not at all dusty compared to other mines.

In the end, Carpenter was able to make only the most obvious conclusion: The disaster was caused by a gas explosion, likely augmented by coal dust. The crucial questions of what ignited the gas, and what systemic failures allowed gas to remain in the mine, remained unanswered. Carpenter made a few recommendations, including better monitoring of fans, removal of workers from the mine while dynamite was being fired, vigorous searches of employees for pipes or cigarettes, and storage of vital mine planning documents off-site from the mine.

The lessons learned at Hillcrest and other mine disasters did lead to some safety improvements, including new provincial regulations mandating controls for coal dust and funding for the proper training and equipping of mine rescue teams. Nonetheless, another explosion at Hillcrest killed two more miners in 1926. Not until the company closed the mine in 1949 was the risk of mining Hillcrest finally removed.

The casualty rates experienced by coal miners are not nearly those Canadian soldiers would experience with the outbreak of World War I, just a few weeks after the Hillcrest disaster. But the sacrifices of workers who built the mining industry in Canada are no less important to memorialize than those of soldiers who died in Belgium and France. A monument at the Hillcrest site captures this idea with its dedication “to the underground coal miners and their families whose hard work and sacrifices helped to establish our communities and our country. They will not be forgotten.”

John Sandlos is a professor in the History Department at Memorial University of Newfoundland and the co-author (with Arn Keeling) of “Mining Country: A History of Canada’s Mines and Miners,” published by James Lorimer and Co. in 2021.

Comments