Progress or peril? First Nations in the Ring of Fire divided on infrastructure – and the mining development it would attract

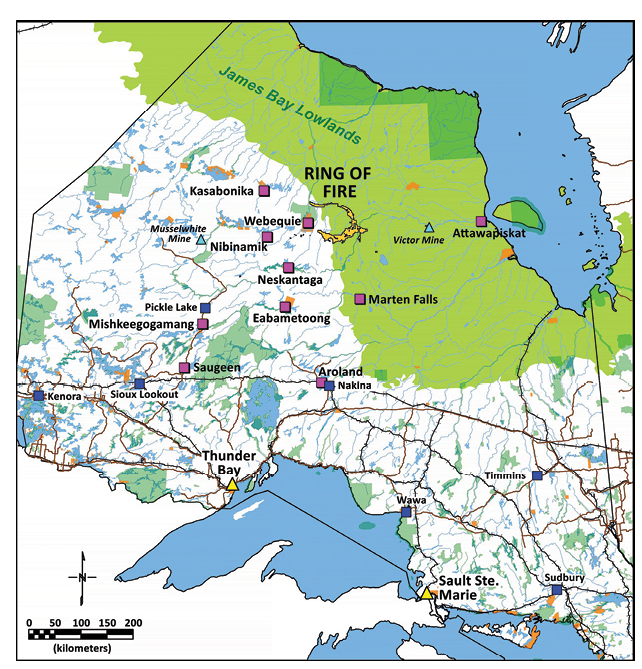

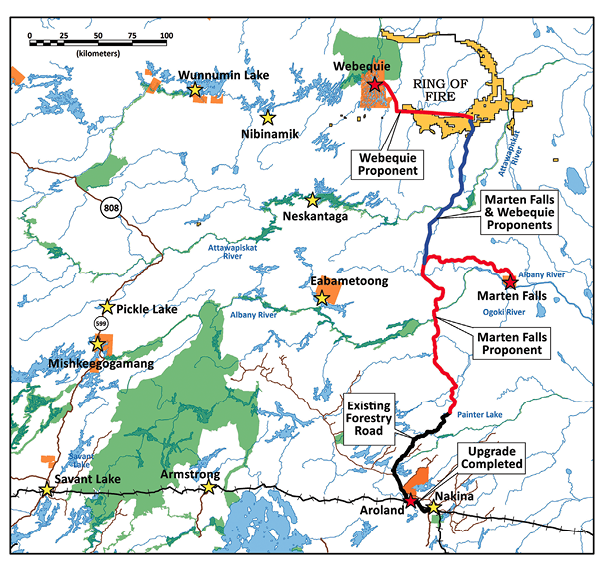

Marten Falls Chief Bruce Achneepineskum is eager to start work on a 200-km permanent, all-season road to his remote, fly-in First Nations community in the James Bay Lowlands, about 170 km northeast of Nakina.

Achneepineskum says the road, which would link to forestry roads near the Aroland First Nation near Nakina, would be a “lifeline into the community,” making the shipment of fuel, building materials, food and other essentials more affordable, and allowing community members to travel more freely. An all-season road is also becoming a more urgent necessity as the winter ice road seasons become shorter and less reliable because of climate change.

The road would bring new, permanent infrastructure closer to the Ring of Fire – still about 120 km to the north.

But in a best-case scenario, it will still be close to a decade before the road could be completed.

An environmental assessment (EA) is under way; assuming it is approved, an engineering study will still need to be completed. And according to the project description, construction would take at least three years – but could take as long as 10, depending on the terms of funding. While planning and design work began in 2018 with the initial project description submitted in 2019, the permitting schedule has been slowed by the Covid-19 pandemic.

“It will probably be four or five years before we see a shovel in the ground,” Achneepineskum says.

However, the project could be facing further delays. In November, about a month after the terms of reference for the road EA were approved by the Ontario government, the Neskantaga First Nation filed an action in Ontario Superior Court, arguing that it has not been adequately consulted on road proposals in the Ring of Fire region – especially considering it has been dealing with a long-term boil water advisory, a community evacuation in October 2020 because of unsafe water, and the disruptive effects of the pandemic that have prevented it from engaging in meaningful consultations.

The suit against the Ontario government, which also names Marten Falls as a respondent, asks the court to define scope of adequate consultation, something that Ontario’s Environmental Assessment Act does not address.

Credit: Noront Resources

In addition to the lawsuit, the chiefs of Neskantaga and several First Nations belonging to Mushkegowuk Tribal Council of communities in western James Bay and Hudson’s Bay, declared a moratorium on any development in the region last year. The chiefs feel they’ve been reduced to token involvement in a federally-led regional assessment of the Ring of Fire that is slated to begin this year.

In an interview with CMJ in February, Marten Falls Chief Achneepineskum said that as the proponent of the road, he was confident with the way the community is handling the EA. Marten Falls has consulted with 23 communities.

“There are going to be First Nations that object to our position and we’ll respect their positions and where they’re coming from,” he says. “But we are assuming our own jurisdiction within our own lands and our environmental assessment falls within Marten Falls traditional lands.”

Nonetheless, Achneepineskum acknowledges there are areas of overlapping jurisdiction with other First Nations, adding that Neskantaga is within its rights to pursue its court action. “That’s part of the issue that we’re facing today is – what does that really mean? Who has the ultimate authority within those lands to make decisions? If Marten Falls is going to make a decision on moving forward with development, and there’s a First Nation objecting, how do we find a resolution to that? Who’s going to resolve those issues?” he said. “I think it’s going to be all parties that have to resolve those issues.”

From one road to four

There have been various proposals for transportation in the Ring of Fire, located 540 km northeast of Thunder Bay, Ont., over the years – including the current north-south route, an east-west road, and a rail corridor.

The north-south route has been broken up into three different segments. While previously, the proposals were industry driven, the proponents of projects currently in the environmental assessment phase are all First Nation.

In addition to the Marten Falls road, Webequie First Nation is also proposing a 107-km supply road between the community and the Ring of Fire camp; and together, Marten Falls and Webequie are proposing the 155-km Northern Link to connect the two roads.

Over the years, Marten Falls and Webequie have both worked closely with Noront Resources, which holds the most advanced nickel-copper-PGM and chromite projects in the region, and which Australia-based Wyloo Metals has offered to buy for $617 million (see page 34).

Mushkegowuk Council communities east of the Ring of Fire are also exploring their own permanent 550-km-plus road. The road would connect western James Bay coastal communities, reaching as far as Attawapiskat First Nation, with the provincial highway system.

Attawapiskat Chief David Nakogee says there’s a key difference between the Webequie and James Bay Road proposals.

“They are inviting industries to come and use their highway and what we’re proposing is for the people, to cut the cost (of living),” he says. “There’s no invitation to industries to come in and I would say invade our territory to start production of everything and anything they can get their hands on.”

Nakogee is also concerned about pollution to the Attawapiskat River as well as James Bay and Hudson’s Bay.

Kate Kempton, Attawapiskat’s lawyer and a partner with Olthuis Kleer Townshend, says while the Marten Falls road may be justified as a community access road, the other two segments of the road are for industry use. Kempton adds that all three were originally part of one road to serve industry.

“Ontario has been the driving force behind this by telling the Matawa First Nations, who used to be working together on a regional approach, several years ago that it would only do bilateral agreements with First Nations and provide funding for capacity building and economic development if the First Nation would appear to be pro-mining. So that was an inducement that led to that,” says Kempton, who adds that splitting the project into three segments with different processes is “immoral.”

Regional Assessment

Complicating the picture is the federal government’s commitment in February 2020 to conduct a regional assessment (RA) of the ecologically sensitive region of boreal forest and peatlands. The request was made by several parties, including Aroland First Nation, one of 34 First Nations in the region.

Regional assessments are a new option under the 2019 Impact Assessment Act. Only one RA – for offshore oil and gas drilling in Newfoundland – has been completed so far.

One of the key goals of an RA is to examine the potential cumulative effects of development in an area – something that project level assessments can’t do – ways those impacts could be mitigated, and priority areas for further study. The process is also meant to incorporate Indigenous knowledge.

But the process, which is still at the draft terms of reference (TOR) stage, is off to a rocky start. The First Nations chiefs that declared a moratorium on development last year say the draft TOR – which will govern the scope of the assessment and the way it is conducted – was drawn up by the federal and Ontario governments with little input from First Nations.

“The Impact Assessment Agency of Canada has breached the honour of the Crown … and the project of reconciliation and decolonization by acting with duplicity behind our backs in collaboration with Ontario, to render the (RA) little but political puffery, with mere token First Nation ‘involvement,’ narrow in its focus and weak in its result,” the chiefs of Attawapiskat, Fort Albany, and Neskantaga First Nations said in a statement.

Instead, the chiefs want an RA process that is co-led by a new Indigenous governing body composed of affected First Nations. They also believe the scope of the assessment needs to encompass a much larger area than proposed in the draft.

First Nations communities have until Mar. 2 to comment on the draft terms of reference. Soon after, if the federal Minister of Environment and Climate Change Steven Guilbeault approves the document, an independent committee would be formed to conduct the RA. The committee would have 18 months to complete its work.

So far, the federal government doesn’t seem inclined to start the process over. While the Impact Assessment Agency has encouraged communities to nominate committee members, it recently told TVO.org that only groups currently defined as “jurisdictions” under the IAA can be signatories to a regional assessment agreement. While the agency said it is developing regulations to broaden that definition, it told the news organization that the process would not be completed before the Ring of Fire RA begins.

However, there have been Indigenous-led project-level environmental assessments in B.C. And Kempton says that should be the case for regional impact assessments under the IAA as well.

“The federal Impact Assessment Act allows for agreements with Indigenous governing bodies and those agreements could and would provide for co-leadership – the Crown and a group of First Nations who are affected would co-lead a regional impact assessment and make decisions mutually,” Kempton said.

“Canadian law allows for it. Our opinion is Canadian law requires it, based on the legal principle of reasonableness. Essentially, it would be unreasonable to not use the mechanism from Canadian law to require this to happen here –

a co-First Nation-led regional impact assessment that is also broad and thorough and comprehensive in scope.”

Kempton says the James Bay Lowlands, as the second largest peatlands in the world, are globally significant as a carbon sink, so it’s imperative to make informed decisions about development there.

“Peatlands are five to fifteen times more effective than forests at sinking carbon, so if we lose them to mining, we lose a critical defence against worsening climate change,” she says. “But also, if they’re radically disturbed or destroyed from mining, all of the carbon that is currently sunk there will be released into the atmosphere and that could be a tipping point that leads to a domino effect into catastrophic irreversible climate change.

“We have to get this right. We have to understand potential direct and cumulative impacts of any development up there because the risks of catastrophe are far too great if you get it wrong.”

For his part, Marten Falls Chief Achneepineskum is participating in the regional assessment process, but says he has no objection to an Indigenous co-led RA process.

He also points out that the Marten Falls EA is Indigenous-led.

Discussing the community road project specifically, he said: “There’s a lot of discussion on the environment, pollution and far-reaching effects. There’s a lot of fear mongering that’s happening, but in the end, we have to base our own analysis and our own decisions on actual facts and science. And that’s what we’re trying to do with our environmental assessment is come up with good studies and a good project that will answer all those questions. Hopefully the regional assessment will also do the same thing.”

Comments