Massive Nickel Job Takes Shape

Vale Canada Ltd.’s $2.8-billion nickel processing facility at Long Harbour in Newfoundland will be a showcase for the mining giant’s newly developed hydrometallurgy refining technology when the plant is completed in early 2013.

Long Harbour, which will process 50,000 tons per year of nickel from the Voisey’s Bay concentrate deposit in Labrador, will operate much differently than traditional nickel processing facilities. The key difference is the use of hydrometallurgy or “hydromet” technology that utilizes a combination of water and oxygen under pressure to dissolve selected metals from the incoming concentrate.

“It is a process called POL, which means Pressure Oxidative Leaching,” says Rinaldo Stefan, who is project director of the Long Harbour processing plant.

For Vale, one of the big payoffs from the POL process is a significantly reduced sulphur dioxide footprint for the Long Harbour operation. As part of the traditional nickel refining process, sulphur is mixed with oxygen to be removed, captured and then converted into sulphuric acid to be disposed of.

In the mining company’s POL process, concentrate is extracted from the sulphide using temperature, an acid PH solution and oxygen under pressure. “So we are actually discharging sulphur as elemental sulphur that ultimately will end up with the iron hydroxide which is one of the byproducts of the process…and gypsum,” says Stefan.

To prevent the sulphur from oxidizing, it will be stored under water in a tailings pond indefinitely at the site. “Basically what it does is it completely reduces your sulphur footprint.”

Annual output of Long Harbour is expected to be 50,000 tonnes of nickel, 4,700 tonnes of copper and 2,500 tonnes of cobalt.

The process starts at the mine site at the Voisey’s Bay nickel deposit where the ore undergoes a first step of purification in a mineral concentrator under a standard flotation process. The ore will then arrive by ship to the Long Harbour plant at a 20 per cent nickel concentration. (The concentrate will also average 2.4% copper and 1% cobalt, according to Stefan).

Upon arrival, the concentrated ore undergoes crushing/grinding to reduce the size of the concentrate feed from 100 microns to 20 microns. The next step utilizes chlorine gas (a refining process by-product) to activate the concentrate prior to the POL process, which leaches the metals into a solution that starts the lengthy separation process which removes first copper, then impurities such as manganese, calcium, lead and zinc and other metals.

Finally cobalt is removed and diverted to a cobalt tankhouse for extraction, leaving a solution containing just nickel that is captured through electrowinning removal. Both the cobalt and nickel are produced as “rounds,” explains Stefan. “Rounds are basically loonie-sized coins.”

“All the metals we are producing (copper, cobalt and nickel), are LME grade metals,” he says. “So they are sellable to market directly; they don’t need further processing anywhere.”

Vale’s hydromet technology to process the Voisey’s Bay nickel concentrate at Long Harbour was the end-product of a 10-year, $200-million R&D program that began with laboratory work and the operation of a 1-10,000 scale mini-pilot plant at the company’s Mississauga, Ont. research centre and the operation of 1-100 scale demonstration plant from 2005 to 2008.

The construction program at Long Harbour is just one part of Vale’s $10 billion capital investment program in Canada that was announced in November 2010. Most, if not all, of the hydromet process was developed within the country, with the support of Industry Canada’s Technology Partnerships Program.

“This is very much a ‘made in Canada’ process and flow sheet,” says Sam Marcuson, vice-president of base metals technology development at Vale.

Marcuson says that much of the refining process that will occur at Long Harbour is new for the company. “We do some of the processes already in Sudbury in our copper recovery circuit,” he says.

The hydromet system, however, was designed solely for its newest facility.

“The process is unique to Voisey’s Bay and suited for Voisey’s Bay, but it is related to other technologies that have been employed.”

Marcuson, a 31-year veteran with Inco and now Vale, explains that the avoidance of sulphur emissions was a key consideration but not the only reason that the hydromet technology was selected for the Long Harbour facility after much study in late 2008.

“It is also more amenable to have at a smaller scale than smelting, and I believe that the original analysis suggested that the capital costs would be superior than for smelting, and operating costs would have advantages as well.”

By way of comparison, the 50,000 ton nickel output of Long Harbour is about half that of the company’s nickel smelting and refining operation in Sudbury and roughly equivalent to the Xstrata (formerly Falconbridge) smelter in Sudbury.

Marcuson says the hydromet process developed at Long Harbour was created with the Voisey’s Bay concentrate in mind and may or may not be used again within the company’s other operations.

Vale currently is in more than 30 countries around the world.

“Right now there is no set ‘cookie cutter’ technology for dealing with nickel sulphides, because a lot of it depends on what are the byproducts and what are the other value metals associated with the nickel,” says Marcuson.

“In the case of Long Harbour, there is a lot of copper, there is lots of cobalt, but there are very few platinum group elements, so the technology is aimed to treat the material in the ground,” he explains.

“In Thompson, Manitoba, there is some platinum group element and there is very little copper. In Sudbury, we have lots of nickel, lots of copper, some cobalt and a large amount of platinum group elements. So the processes are being tailored to treat the deposits. So in some respects this is the first real development for us in using pressure oxygen leaching of a sulphide which could provide the model for the next time we come up against like this.”

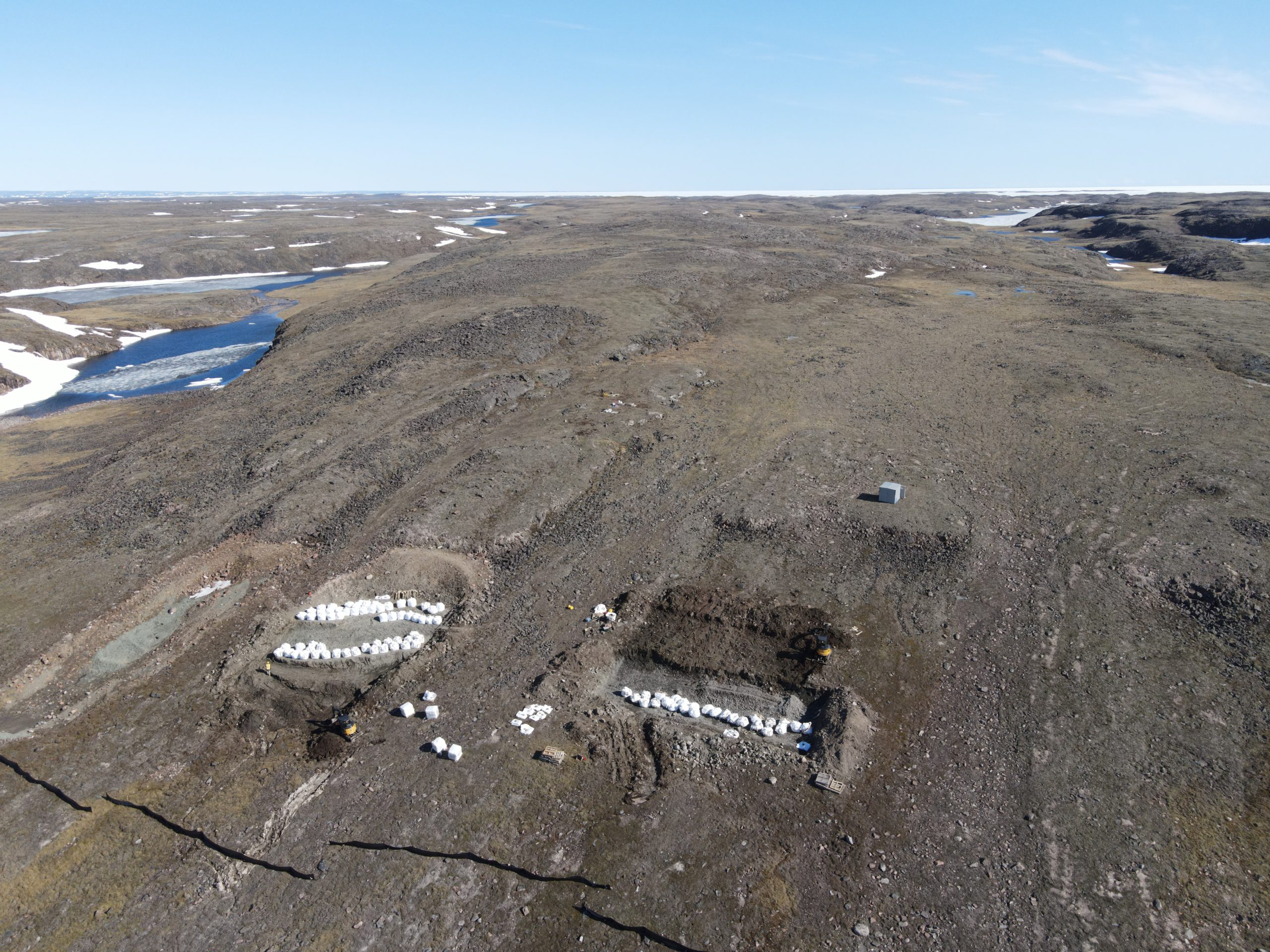

In June, Vale provided a status update on the Long Harbour processing plant. Having embarked on initial construction in February 2009, engineering work at the site was about 80% complete, construction 20% complete and overall project completion currently stands at about 40%.

The status of current construction includes substantial completion of earthworks and building foundation concrete, the delivery and installation of the first electrical room and making the camp and lodge operational.

The Long Harbour project is employing 1400-plus workers at the construction site engaged in 26 contracts, another 120 at the St. John’s engineering and project management office and about 600 at Vale’s engineering offices in Vancouver and Calgary.

Vale is currently refining Voisey’s Bay ore at its plants in Sudbury and Thompson and looks forward to the day that the process will be a much more local affair, says John Pollesel, the chief operating officer of Vale Canada Ltd. and director of base metals for the North Atlantic region. “It is a totally integrated operation for the province of Newfoundland.”

Besides eliminating the time and expense of shipping the concentrate to Ontario or Manitoba for refining, Long Harbour is expected to deliver one other benefit, says Pollesel.

“Our expectation would be that we would actually achieve higher metal recoveries.”

Comments