Lundin Gold prepares to bite into Fruta del Norte

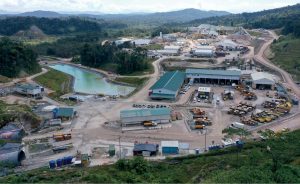

Lundin Gold’s Fruta del Norte mine, in Zamora-Chinchipe province, Ecuador. Credit: Lundin Gold

When Lundin Gold pours its first gold at the Fruta del Norte mine – an event that is expected in the fourth quarter of 2019 – it will prove that the company was right to take a chance on mining in Ecuador back in 2014.

Despite its promising geology shared with other Andean nations, Ecuador is only seeing its first, large-scale modern mines this year – starting with the Mirador copper mine north of Fruta del Norte (FDN). And the journey to advance mining in the country hasn’t been without its perils. FDN’s previous operator, Kinross Gold, spent several years trying to advance the project after buying it for US$1.2 billion 2008 – only to walk away after being unable to negotiate a revenue sharing agreement with the government. With Lundin now on the cusp of opening the country’s first large gold mine, in Zamora-Chinchipe province, it is both an exciting and delicate time for the single-asset company.

So what’s been the key to Lundin’s success so far at FDN over the past five years?

Lundin president and CEO Ron Hochstein led the company’s due diligence efforts leading up to the US$240-million acquisition from Kinross Gold in 2014 and has been at the helm at FDN ever since.

Hochstein, who has a long history of working with the Lundin family, says that the Lundins have a knack for sensing when an untested jurisdiction is ready for outside investment and for finding ways to work with governments.

“The family going back to Adolf and Lukas and I think now with the sons, have this innate ability to understand and be able to talk to people,” Hochstein told Canadian Mining Journal in November from Quito. “Lukas came down and we met with several government ministers and he could sit there and say ‘I’m willing to invest the family’s money here – are you guys serious about moving forward?’”

The Lundin family, known for oil and gas and mining investments around the world, is a major investor in all Lundin Group companies and Lukas Lundin is chairman of Lundin Gold.

“Our whole philosophy is we’re doing this with the country – this isn’t us coming in and we’re going to build a mine and then take all the gold,” Hochstein says.

As part of that philosophy, the company has invested heavily in local training and local procurement. With the Lundin Foundation, the company put together a procurement program that now results in spending of over $2 million per month in a region that had a total GDP of $60 million before its arrival.

The company’s success has also been a matter of the right timing.

Ecuador’s economy has a high dependence on oil, and when Kinross was trying to advance the project, oil prices were flying high. Since oil prices have come down in late 2014, the government has put a big emphasis on growing its mining industry.

As the real and perceived barriers to investment have fallen away – including the infamous 70% windfall profits tax, which current President Lenin Moreno recently formally abolished – other mining companies have begun investing in Ecuador, including BHP Billiton, Anglo American, SolGold, INV Metals and several Chinese owned companies.

Tight timelines

From the beginning of Lundin’s involvement with FDN, there’s been pressure to move quickly.

“From the time we signed the deal (with Kinross) in December 2014, we had 18 months to complete a feasibility study,” Hochstein says. “Kinross had done a bunch of work but when we started really getting into it that was a tall order.”

Lundin completed a positive feasibility study in June 2016, which then allowed the company to negotiate an exploitation agreement and an investment protection agreement with the government later that year, and receive an environmental licence that fall.

After that, Hochstein says the company moved forward with financing and developing the project to advance as quickly as possible.

“I think, too, our timing was perfect because with (former President Rafael) Correa’s administration, everyone in government knew what their responsibilities were and what they were expected to do,” he adds. “So we had a lot of support from the government to move forward and get all our agreements done,” which Hocstein says were done with fairness.

“Essentially all those agreements do is say this is the laws that are in place at this point in time. We don’t get any special tax holidays or anything like that, it essentially says here are the laws that were in place and this is what we’ve agreed to.”

Hochstein notes that special tax holidays or treatment “can go south on you really quick.”

Development of the underground project has been swift: Construction, including ramp construction began in May 2017 and was followed by other facilities at the planned 3,500 t/d operation. Connection to the national power grid via a 42-km power line was completed this fall. And as of early November, project construction was 89% complete and commissioning of the process plant was under way. In late September, mine production was on plan with about 150,000 tonnes of ore stockpiled.

The US$692-million mine is expected to produce 310,000 oz. gold per year or 4.6 million oz. in total over a 15-year mine life. And there is potential for mine life extension as the deposit is not fully defined to the south.

Last permits issued

With all of that accomplished, there have been a couple of hiccups on the way to production.

Ecuador saw Indigenous-led anti-austerity protests in early to mid-October. The mass protests shut down highways and were marred by chaos, some violence and a temporary relocation of the national government from the capital of Quito, as well as several protester deaths. The protests were aimed at the government’s elimination of a four-decade-old fuel subsidy, which has been reinstated.

Hochstein said that things have calmed considerably since the protests ended. Moreover, they haven’t thrown FDN off schedule.

“The shutdowns were not focused on the mine at all, we just had shutdowns of personnel and supplies primarily due to several road blockades on the national highways,” Hochstein said in early November. “It’s been pretty calm here since then, but I think people are on edge.”

At presstime in mid-November, the last remaining hurdle to production at FDN was resolved: permitting.

Lundin needed two permits – one it applied for in December 2016 and the other in January 2017 – to begin production. It received them both from the agency SENAGUA (La Secretaría Nacional del Agua) on Nov. 14, shortly after changes the national government made at the ministerial level in October.

The previous minister in charge of SENAGUA resigned in early October and a new interim minister, Marco Troya Fuertes, was appointed in mid-October.

Under the previous minister, Hochstein said SENAGUA had been an “obstructionist” agency and had not been issuing water permits for any type of project, including mining, oil, infrastructure or power.

But shortly after Troya’s appointment, Hochstein said the company received copies of a letter from the president to the new minister saying that it was important that all permits get moved, including the ones for Fruta del Norte. The company was also able to meet with the new minister and later host him at site.

Community support

Hochstein says Lundin Gold has good local support thanks to the positive relationships built by both Aurelian Resources, which discovered the FDN deposit in 2006, and Kinross, as well as its own focus on local employment and procurement.

The company worked with the ministry of education and an NGO called Fe Y Alegria on an accelerated high school program that was the first of its kind in Ecuador to help locals upgrade their education. Lundin has also invested about $10 million on training locals in underground mining and for process plant jobs. The program, which involved simulators, has graduated well over 200 people from the local community, county and province. The mine will employ 900-1,100 people when in production.

In terms of local procurement, Lundin has found capable contractors with experience in oil and gas and power projects that has proved transferrable to mining.

“I think because Ecuador has a strong oil industry, the education level’s very high – so there were a lot of the trades and that type of thing that we were able to rely on.”

Underground mine development work was awarded to Chilean mining contractor Mas Errazuriz and a civil construction contractor from Ecuador called Semaica.

“That was a perfect match because they did a 50/50 consortium and now there’s an Ecuadorian company that can say, ‘Yeah, we helped developed Fruta del Norte,’ so they have that mining expertise in house.”

Other mining projects have run into trouble in Ecuador, including several owned by Chinese companies. EcuaCorriente’s Mirador open pit copper mine and the San Carlos-Panantza open pit copper project in Zamora-Chinchipe province have both been targeted by Indigenous protesters. And Ecuagoldmining’s Rio Blanco in Azuay province has been halted by court order because of a lack of consultation with local communities.

Hochstein says that Chinese-owned companies operating in Ecuador are starting to improve the way they work with local communities and in implementing responsible mining.

He’s not necessarily worried about a backlash against mining spreading to include Fruta del Norte because of the high local support the project enjoys.

FDN’s remoteness as well as its location in the Amazon, where water scarcity is not an issue have also helped avoid issues other projects have seen.

The project is 139 km east-northeast of Loja, Ecuador’s fourth-largest city, 40 km from Los Encuentros, and about 9 km from a smaller village called San Antonio.

“Where we are and at Mirador, we’re in the Amazon rainforest. We have 3.5 metres rainfall a year, so people are never too concerned about where they’re getting the water from and both of us are focusing a lot on making sure any discharges, which are small, meet all the criteria – both national and international,” Hochstein says.

“In Azuay province it’s a little different – you’re in the highlands so a lot of people are reliant on rainfall or glacier water so there are some concern that mining may have an impact on their water sources.”

Hochstein notes that as a Canadian company, responsible mining is a given.

“Certainly for the Canadian mining industry, community involvement, the protection of the environment, all those things, that’s just kind of a given. But here, we’re teaching Ecuadorians about responsible mining and what that means. The Canadian government has been a huge help for us and Lundin Gold being a Canadian company has certainly helped.”

Comments