How to improve the competitiveness of Ontario’s mining industry: Interview with Chris Hodgson

Our annual review on the state of mining in Ontario must highlight the Ontario Mining Association (OMA). The voice of the mining industry in Ontario was established in 1920 to represent the mining industry of the province. It is one of the longest serving trade organizations in Canada. OMA has a long history of working with governments and communities to build consensus on issues that matter to the mining industry and to the people of Ontario. Chris Hodgson (CH) is the president of OMA. He leads all OMA activities and represents the association publicly. Chris is a member of OMA’s board of directors and its executive committee and provides broad policy guidance to the OMA chair. Recently, I had the opportunity to discuss the most recent mining topics and concerns in Ontario with the best person who can talk about mining in Ontario, Chris Hodgson.

Chris Hodgson joined the OMA following a distinguished career in government. He entered the Legislature following a by-election in 1994, and he won general elections in 1995 and 1999 representing the riding of Haliburton-Victoria-Brock. While in government, Chris served in several positions including minister of northern development and mines, minister of natural resources, chairman of management board, and minister of municipal affairs and housing.

CMJ: To start the conversation, can you please talk to us about your journey until becoming the president of OMA?

CH: You are going back to ancient history here! I have been the president of the Ontario Mining Association for over 18 years. I started on Oct. 15, 2004. I followed Patrick Reid, who had been in the position for 20 years prior to that. It has been a long time and a great experience. Before that, I was minister of northern development and mines for several years. I have been to many mine sites, and I knew all the issues, so when the OMA board approached me, I thought that would be a good thing to do for a short term, but the people were great to work with and it turned into 18 rewarding years.

CMJ: Can you talk to us briefly about the history of OMA and how it contributed positively to the mining sector in Ontario?

CH: OMA was founded in 1920. So, we are one of the longest serving trade organizations in Canada. It developed in the late 19th century when all kinds of minerals were being discovered in Ontario. In the 1920s, some of these deposits became very economical and catapulted Ontario into being the most prosperous province in the country.

The wealth that came out of those mine sites helped to build the province and supported Canada’s development as an industrialized and globally competitive nation. So, our founders decided that they would like to have a common voice and started this association in 1920. The first chair of the board was Arthur Dorland Miles. He was also the president of Toronto-based International Nickel Company of Canada, which was formed in 1916. The purpose of the association remains consistent with our mission today: to improve the competitiveness of Ontario mining industry while promoting safety, environmental stewardship, and sustainability.

Over the years, OMA has maintained its core commitment to this mission and embraced the progressive changes that have come along with more knowledge to make sure that we continue to be more sustainable and protect the environment better, while improving the safety for our workers. Our focus is still on making sure that the mining sector in Ontario is competitive in relation to other places in the world.

CMJ: What are the main goals of OMA? Did you have to make changes to the mission and strategic goals when you became president?

CH: No, it did not change much. The technology has changed. Developments in digital technologies, analytics, electrification, and autonomous operations, as well as changes in management techniques, create a massive opportunity for mining to increase efficiency, enhance environmental protection reduce the carbon footprint, and continue to improve the safety of our people. Safety is our top priority, and we are proud of our sustained collaboration with the unions, governments, and organizations dedicated to sharing leading practices in occupational health and safety. The result has been an impressive 96% improvement in lost time injury frequency in the 35 years from 1975 to 2010, which made Ontario one of the safest mining jurisdictions in the world and mining one of the safest industries in the province. Today, we perform better than the WSIB industry average. In Ontario, after years of struggle with a confrontational approach, where everybody would lawyer up, we managed to establish a collaborative culture to achieve our collective safety goals through shared responsibility and continual improvement. We have taken the same approach to environmental stewardship as well. Our responsibility is to make sure that mining benefits everyone involved, especially local communities and First Nations.

CMJ: The Ontario government announced a five-year critical minerals strategy 2022-27. From your perspective, do you think that Ontario is now ready to meet and benefit from the soaring global demand for critical minerals?

CH: We are well-positioned for this challenge. There are a couple of things that came together. One is trying to become carbon-neutral to fight climate change. This calls for shorter supply chains that use less energy. Our mines are close to the major manufacturing centers in central Canada. The second is that the geopolitical risk with the war in Ukraine, the growing tension with China, and Covid-19 really brought to light that supply chains are fragile and that maybe we should be looking at “friendly shoring,” that is, making sure that our supply chains are shorter and closer to home.

The electrification of our economy is going to require a lot of critical minerals, and the digital economy requires even more critical minerals. There are only a few places in the world that have critical minerals, and we are fortunate to be one of these places. We also mine them responsibly – with high standards in safety, environmental protection, and respect for workers and communities. Our traditional advantage has been that we have had clear, honestly applied rules. So, if you invested money and you followed the rules, you would get a return on that capital. That also meant that we have been able to borrow money cheaper than some other jurisdictions, who do not have the rule of law, and we have been able to pay people more money.

We have every opportunity to become a global supplier of choice for critical minerals. As an industry, we also want to make sure that we meet, in a timely fashion, the requirements for carbon neutrality, and that is also going to require more critical minerals. The government’s Critical Minerals Strategy is a step in the right direction for making this happen – it is a well-thought-out plan that considers input from the OMA and other key stakeholders.

CMJ: In your opinion, what should the provincial government do to help Ontario’s mining sector realize its true potential and create more high-quality employment opportunities in the critical minerals sector?

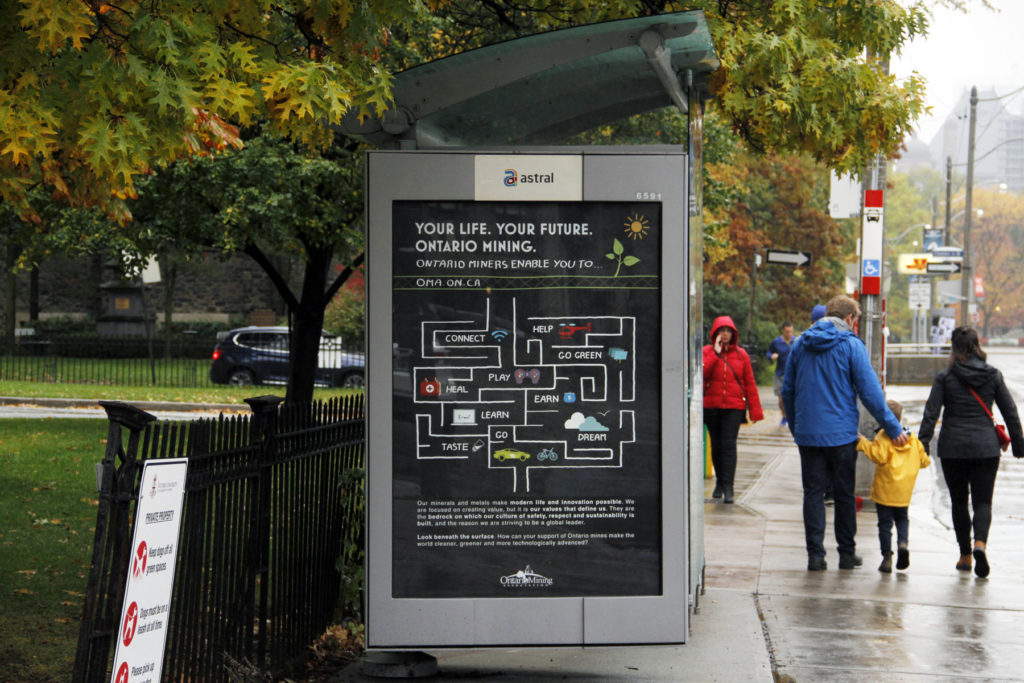

CH: Ontario is blessed with great geology. Mining is one of the only sectors in the Ontario economy where we can truly claim to be a global leader. We offer well-paying jobs and opportunities to make a difference, but we need more people, e.g., skilled tradespeople, engineers, and environmental specialists. It is discouraging to see that the number of people graduating from STEM programs and going into mining is declining. We must work with the government to improve that. One of our major initiatives this year is a campaign to support recruitment that builds on #ThisIsMining, which invited Ontarians to join us in discovering all that mining in Ontario has become over the first century of OMA’s existence, and all it has to offer today. Now, we want to home in on creative and collaborative ways to encourage more people to commit to education and career pathways in mining.

Everybody says it is about rebranding mining positively. However, the latest polling shows that people understand the importance of mining, and I have never seen support like this from the public in Ontario. People now recognize the importance of critical and other minerals, especially copper and nickel, for the electrification of the economy to fight climate change.

CMJ: How about the fact that women only represent 17% of the mining workforce?

CH: That is a great opportunity; bringing this percentage closer to 50% can help solve our employment challenges. Ontario’s mining companies are implementing diversity and inclusion policies to increase the share of women and other underrepresented groups in the workforce. These include PPE for women, training on diversity and inclusion, and career development programs. Almost 70% of OMA members reported that they have gender diversity and equity targets with respect to positions of authority. The mining sector also has one of the highest proportions of Indigenous workers of all industries in the province, at 11%, nearly double the percentage of the Canadian population that identifies as Indigenous. That is another area where we see an opportunity to make sure we encourage people with the right skillset to join the mining workforce.

The government realizes that what we produce is critical for the whole world, and for Ontario’s manufacturing and economy – our minerals are the first link in a strong domestic supply chain. We need to produce EVs, batteries and other green technologies. We have the components that go into those, and the manufacturing will follow.

But to achieve success, we need more people, more talent to go into mining. The Ontario government recognizes this. So, they are helping with partnerships for education and training. One of the pillars of the government’s Critical Minerals Strategy is growing the labour supply and developing a skilled labour force, and we are hoping to work with them on implementing that strategy.

CMJ: How can OMA help in resolving issues with the Indigenous communities? Considering the recent disagreement between the Matawa First Nation and the provincial government in Ontario, do you think the provincial government is doing enough to promote further Indigenous participation in mining?

CH: There is a general approach that we think should be taken when working with Indigenous communities and organizations that aligns everyone’s interests. It is consistent with Ontario’s advantage of having clear rules, honestly applied that benefit everyone. All the operating mines we represent work with First Nations, not just those in the Ring of Fire. They contribute to regional communities by prioritizing local hiring and suppliers, supporting health and education initiatives, and concluding various types of agreements related to mine development. This includes impact benefit agreements (IBAs), which have become standard business practice for mining companies to secure support from affected Indigenous communities to proceed with planned developments carried out within their traditional territories. According to Natural Resources Canada, currently there are over 140 agreements in place between Indigenous communities and mining companies across Ontario.

We have also always supported resource revenue sharing (RRS). In 2018, Ontario signed three RRS agreements, covering 35 participant First Nations, and these agreements have helped align interests between Indigenous communities and the mining industry to help incentivize community engagement and support for responsible mining projects. We would like to see the current agreements being renewed beyond the current five-year term, and more RRS agreements being signed with other impacted communities in Ontario. It is a model that works well.

In terms of the Ring of Fire, previous and current governments have all consulted and worked with First Nations. We supported their approach, which aims to make sure that mining companies are wanted in the communities, and they made good progress in several communities that are now conducting environmental assessments. The government has good intentions and is trying to work collaboratively with the local communities, especially the remote Indigenous communities, but there are always going to be issues to resolve. I think the government is working towards making sure transparent and predictable systems are in place. We are not there yet, but it takes a lot of time to build up the necessary trust.

Our members have been building trust by taking a partnership approach to community relations. They address concerns through proactive communication and engage communities in the process of creating sustainable value at the local level. But companies need clear advice from the government on who they should consult with, and how that consultation should take place. The OMA has been advocating for a centralized assertions unit within the Ministry of Indigenous Affairs to provide consistent and prioritized lists of potentially affected Indigenous communities requiring consultation for resource projects. Having this one-window coordination process will create more certainty with regards to consultation and accommodation, thus helping us to reduce risk and move forward with strategic mineral development.

Ultimately, our members only go where they are wanted, and they make sure that everyone benefits. Building trust is essential, and it helps to have a track record that says something… which helps people understand that mining is a temporary land use, and that responsible companies do their utmost to minimise environmental impacts and, when a project is finished, they make sure that the lands revert to as close to their original condition as possible, so they remain usable for future generations.

Finally, all levels of government are now talking about the importance of mining for decarbonizing the world and making economies more sustainable. This is true. The world does need what we have right now, and we have an advantage over other jurisdictions, because we mine responsibly and with a comparatively small carbon footprint, because our electricity grid is virtually carbon free. We can contribute to making the world a better place not just for local communities, but in a global sense.

Comments