Historic Deloro mine returns to nature

Ontario, like most provinces and territories in Canada, is riddled with working mines and an equal number of historic sites where mining was once the mainstay of economic activity and support.

From its northern-most reaches of Hudson Bay, to the new and promising lands of the “Ring of Fire,” to farther south and the world-famous regions near Timmins and Sudbury with their abundance of producing mines, Ontario is undoubtedly one of the richer mining areas in Canada, if not the world.

Historically, Ontario is known for big names like Hollinger, Noranda, Falconbridge and Inco, for helping develop the province into the powerhouse of mining that it is today, but there were also a number of smaller, yet equally significant companies that played an important role in giving Ontario its international status.

The Canadian Consolidated Gold Mining Company, for example, (a British-based company) started mining gold at its Deloro Mine near Peterborough, Ontario, in 1873.

In the “valley of gold” named Deloro, gold was first discovered in 1868 but it wasn’t until Canadian Consolidated Gold Mining came on the scene five years later and began mining in ernst did the southern Ontario site become known.

For nearly a quarter of a century, Consolidated Gold worked the site but in 1896, because of poor recovery methods, the company sold the Deloro Mine to Canadian Gold Fields Company and the first mill was built.

Using a new cyanide technology to extract the gold and with enough financial support to build roasting furnaces to remove the arsenic from the gold, the new owners were on their way to successfully operating one of the more modern mines of its time.

From 1896 until 1903 when the mill was closed due to the poor grade of the gold, Canadian Gold Fields worked hard and steady to make the mine work. However, following the closure of the mill, a number of uses were subsequently found for it, including the processing of silver ores and the production of cobalt and stellite. (stellite is an alloy of primarily cobalt and chromium). It was very important in the manufacture of munitions in the 1st and 2nd World Wars. Deloro was the exclusive supplier of stellite to the Allied Forces.

The Deloro Mine’s original mill eventually became known as the Deloro Smelting and Refining Company Limited, and was enlarged to include a primary treatment plant, an oxide building, an oxide refining building, a silver refining building, an arsenic bag house, an arsenic chamber building, an arsenic pack house, and a variety of other buildings for precision casting and manufacturing of cobalt metal alloy.

But one problem still remained; what to do with the tons of arsenic* that remained from the manufacturing process?

Unthinkable by today’s standards, but stock piles of arsenic and other hazardous materials were buried or just left on the surface.

(*Arsenic may have been a by-product but it was also a lucrative commodity. Deloro was the largest North American manufacturer of arsenic based pesticides. The problem with arsenic stock piles only emerged after organo-chloride pesticides became the preferred product).

Along with arsenic, the site had been polluted from various mining operations and included waste products with low-level radioactive properties, material stemming from the smelting of uranium ore operations. Compounding the problem were also approximately 90,000 tonnes of ferric hydroxide (red mud) that were pumped as waste slurry from the hydrometallurgical plant to the tailings area from 1914 to 1961 on the 202-hectare site.

Nearly a century’s worth of hazardous by-products and residues – a complex blend of toxic compounds; metals like cobalt, copper, nickel; and low-level radioactive wastes. Each of these materials causing significant environmental impact at the site, including contamination of the site’s soil, sediment, surface water and groundwater, posing a potential threat to nearby communities and watercourses.

In other words, a large scale environmental problem.

And that’s where the story of the Deloro Mine Site Cleanup begins.

In April 1979, the site was abandoned by the final private property owner, Erickson Construction Limited who declaring a lack of operating funds following Ministry of Environment orders, the property was escheated to the Crown in 1987 but the ministry was unsuccessful in recovering costs.

More than 30 years later, significant progress has been made at the site, with the Ontario Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change (MOECC) spending more than $75M to date on this project.

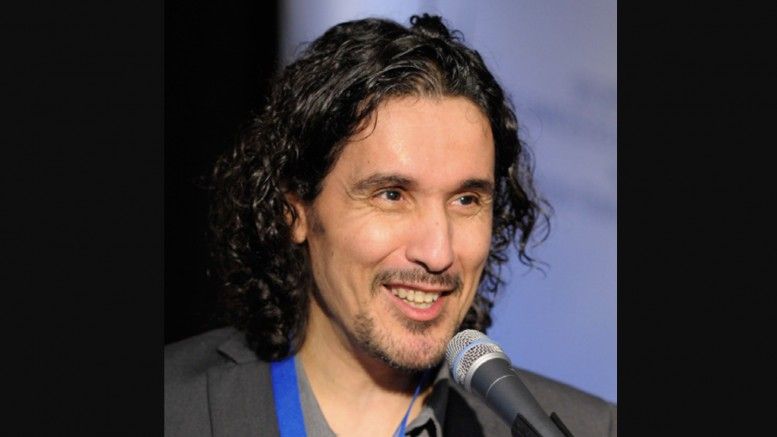

Robert Putzlocher, Deloro Project Engineer with the Ontario Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change says “The goal of the clean-up is to isolate and contain contamination on the site itself to keep it from getting into the environment. We’re doing that by building two engineered covers and an engineered containment cell, and by managing ground and surface water.”

A top priority of the ministry was protecting the neighbouring Moira River, which runs through the site and flows into the Bay of Quinte on Lake Ontario. As recently as 1983, an average of 52 kilograms of arsenic were going into the Moira River every day.

To help solve this problem, Putzlocher says that an arsenic treatment plant has been built and operates daily, to collect and treat arsenic-contaminated groundwater from the mine site. The plant includes an 80-metre underground concrete wall to stop groundwater from getting into the Moira River, a clay-lined contaminated-water holding pond, and nine pumping stations. The plant removes 99.5% of the arsenic found in the contaminated groundwater.

In addition, the ministry has sponsored projects involving the installation of extensive ground and surface monitoring networks, locating and sealing all old abandoned mine shafts, demolishing derelict buildings and the construction of an on-site laboratory to analyze ground and surface water samples.

From 2011 to 2013, the ministry contracted Golder Associates Ltd. to perform the more specific tasks of the Tailings Area Clean-up and Phase 2 of the Industrial and Mine Area Clean-up.

Golder, while working as General Contractor for the MOECC, also self-performed the required QA/QC for the civil remediation works, radiation monitoring, water sampling and analysis and air quality monitoring required during the operations. For more than three years, Golder concentrated on securing the site contamination by building a groundwater collection system and upstream surface water flow diversions to meet the project’s objective of limiting infiltration to less than 10 per cent of annual precipitation and thereby reducing the discharge to neighbouring waterways.

At the large tailings area on the east side of the former mine site, Golder installed over 26 hectares of geosynthetics, 300,000 tonnes of fill material and planted more than 10,000 poplar trees to complete the capping of the area and restore it to a natural condition.

Its work continued in the Industrial Mining Area (IMA) located to the west of the Moira River. Heavily contaminated wastes were placed within the site’s waste consolidation area (WCA), with final design planned to include a cap of engineered geotextile, geosynthetic clay liner, layers of clay fill, sand and re-vegetation of the area.

Golder Associates Construction Contracts Manager, Brian Daniels, says the $21M cleanup projects posed several challenges, specifically with workers and exposure to low-level radiation. “We developed and executed an extremely intricate Radiation Protection Plan for workers at the Deloro project,” says Daniels, “resulting in 100% compliance with the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission, the Ministry of the Environment regulations and most importantly, resulting in a safe working environment for our people over our

years at Deloro.”

In 2013-14, work continued on the consolidation of waste into the Industrial and Mine Area WCA. In addition, the Ministry successfully commenced cleanup operations in Young’s Creek in preparation for a large scale dredging project focusing on removing impacted sediment from the creek bed.

The project is expected to be completed by 2017.

Putzlocher says: “Ontario is finishing the clean-up of the abandoned Deloro mine site so that we can continue to improve water quality in the Moira River. The site will be engineered to be safe for people and the environment for hundreds of years.”

Comments