Fire River Gold revives Nixon Fork project in mining-friendly Alaska

The long days of the Alaska summer are lighting up a remote, decades-old gold property that Vancouver junior Fire River Gold Corporation hopes will launch it into the lucrative league of gold producers riding the metal’s sustained bull run.

“Very few juniors have a chance to get into production, and this one has an excellent chance to become profitable producer,” says President and Chief Operating Officer, Richard Goodwin.

He’s leading an experienced team of Canadian and American professionals in reviving a property that charts its history back to the 1920s and a clanking gold-stamp mill that pounded out four ounces per ton.

Since then the remote south-central Alaska find, among a swath of mines clustered along the vast Tintina gold belt, has had a series of on-off production runs. The latest was by another Canadian miner, St. Andrew Goldfields Ltd., which gave it up after only five months in 2007, halted by dismal gold recoveries and near-fatal corporate distress when the company faltered under the global economy meltdown.

St. Andrew’s has since recovered, but it had to jettison the well-equipped Nixon Fork camp (estimated at $150 million Cdn replacement cost) at a bargain basement $500,000 US. That price, and the fact that it was fully permitted, made Nixon Fork a prime opportunity. (The mine was actually built by Nevada Goldfields, and between 1993 and 1999, until low gold prices forced its closure, it recovered 138,000 ounces of gold and 2.1 million pounds of copper.)

Overall, Nixon Fork looked like a good fit for International Metals Group, the Canadian group of mining executives and investors who have far-flung gold, base metal and platinum group metals interests in Quebec and Congo as well as Alaska. IMG created Fire River Gold in 2009 to exploit the Nixon Fork property.

Benevolent Alaskan mining climate

Goodwin, a professional engineer with over 25 years in underground mining and management at Westmin Resources, MRDI Canada, Snowden and Redcorp Resources, says the location really had no bearing on the Canadian company’s strategy.

“The fact that it was in Alaska was irrelevant… the fact that it’s in a safe region, and that it was permitted, was enormous. What you want is a place where you have a high degree of success and you’re not going to get blindsided by random government actions. Alaska is certainly a very good state to deal with.”

Alaska has what’s called the Large Mines Permitting Group, which assigns one representative for all State activities. “So we can deal with one person who coordinates… any aspect of permitting, which we find quite helpful,” says Goodwin.

Another distinction favouring Alaska, says Goodwin, is the business approach adopted by its First Nations. While Fire River Gold’s lease is on public land that predates statehood, it is surrounded by land owned by the Doyon, one of 12 Alaskan native groups included under the State’s 1971 native land settlement act.

“They’ve been extremely good neighbours… we work quite cooperatively with them. One very good aspect of dealing in Alaska is the native nations. They function like corporations, very much like dealing with another business,” says Goodwin. Several Doyon shareholders (members) work at the mine, and the catering is contracted with Nana Corporation, another Alaskan First Nation.

Labour hard to find

Despite – or perhaps because of – Alaska’s mine-friendly culture and economy, recruiting workers to upfit and operate the 150 tonne-per-day mine and mill is proving a challenge, says Goodwin. The minimum worker requirement is a 40-hour MSHA (Mine Safety and Health Administration) course as well as a day-long on-site orientation.

Like other remote Canadian sites, the bigger barrier to hiring may be its isolation. The Nixon Fork property is perched among rolling, boreal forest 56 km from McGrath, the nearest village, and 360 km from its logistics and supply base at Anchorage.

This summer, about 90 builders and miners will be on the payroll working four-and-two week rotations. Sixty are at site working 12-hour shifts, while the others are out on their two week leave. Technical staff works a two-and-two week rotation.

It is exclusively a fly-in operation, making it a stand-out even among Canada’s most remote mines which have at least seasonal access by winter road or ocean tidewater. One of Nixon Fork’s key assets is a 1.2 kilometre gravel strip used by heavy-lift transporter Lynden Air for its C-130 Hercules, and Evert Air Cargo’s DC-6 for its fuel resupply. Routine traffic is chartered through Alaska Air Transit and its nine-passenger Navaho Chieftain aircraft, all based out of Anchorage.

“It is set up be a fly-in only operation, and logistics will always be a very strong component of operations, we have to keep managing that correctly,” he cautions, adding, “but if you have to be in a remote location, gold’s what you want to be mining.”

Case in point: the landed cost of a gallon of fuel is $6, and the mine will need 700,000 gallons a year.

Low tonnage needs high grade

The Nixon Fork mine will harvest a projected 50,000 ounces a year at a cash cost of approximately $500Cdn per tonne for mined gold, yielding a pre-tax income of $40 million based on $1,400 gold. Inferred and indicated reserves grade as high as 27.8 grams per tonne. Goodwin says the first six months of production will be from pockets of readily accessible ore.

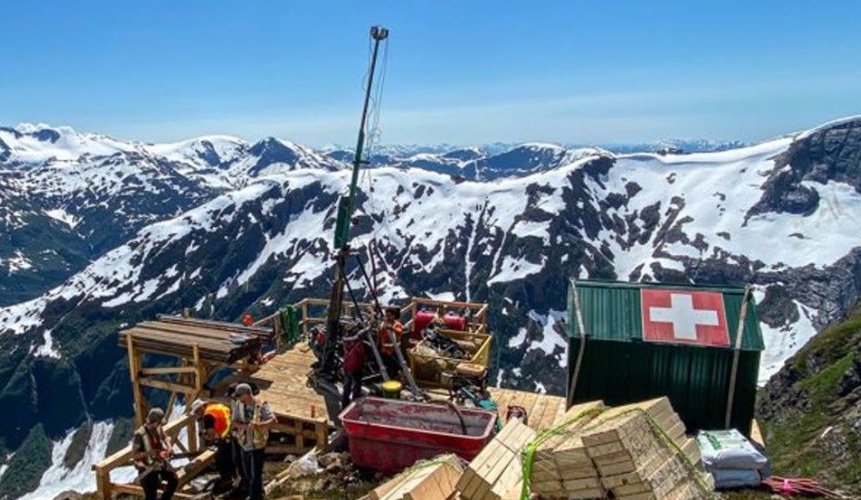

Some 20,000 meters of recent diamond drilling have defined the deposit. The company’s exploration strategy is to find at least one year’s reserves in advance, to keep the 150 tonne-per-day gravity, flotation and [newly constructed] cyanidation circuits going to meet a 96 per cent recovery target.

Rehabilitation has been declared complete, said a company release July 4th, and the gradual process of starting and conditioning the mill began that day.

Nixon Fork is essentially two ore bodies, accessed by ramps to a depth of about 300 meters. Goodwin says that along with the new cyanide circuit, he’s doubling the capacity of scoop trams to four yards, and trucks to 20 tonnes, but otherwise is not bringing in any major changes.

“The main challenge is grade,” says Goodwin. “We’ve got to achieve high grade, it’s a low tonnage operation. The ore body does have high grade pockets, so the challenge is to find them in sufficient cohesion. At 150 tonnes a day, it has to be very high grade to carry the cost…. the mill cannot be easily expanded, but may be in the future”.

While silver and copper are also present, 90 per cent of the production by value is gold. Silver/gold dore bars will be refined in Utah, while copper/gold concentrate will likely go to Asia.

Nestled in a skarn deposit some 26 kilometres around, Goodwin says probably 10 per cent has been probed. “All around that perimeter is potential for good exploration sites.” The deposit’s metamorphic geology also has the advantage of leaving a “very clean” tailings and drystack footprint.

Jumpstart for more Alaskan mining

A preliminary economic assessment pins Fire River Gold’s capital costs at $6.3 million Cdn with a speed-of-light payback of a mere three months, given operating costs of $447 per ounce of gold.

But Goodwin and his team are dealing with the realities of an admittedly complex geology, in a wild and remote place with big logistical and transportation needs (reminiscent of the now-mothballed Lupin gold mine in Nunavut, a 2,000 tonne per day mine built entirely via by air in 1982 from Yellowknife- – a 1000 km roundtrip).

And an old mine, after a series of owners, also comes with its own quirks; geologists are trying to make order of some 120,000 meters of old drill core.

But when Fire River Gold begins shipping concentrate and pouring dore this summer, it hopes it will be the beginning o

f a long and healthy future in gold, including the optioned Kansas Creek property, a placer producer with lode gold potential 110 km south of Fairbanks, along with the Draken project, its first Alaskan holding, 288 km southeast of Fairbanks.

“What we want to do is get this project going, get us into profitability and grow the company,” says Goodwin. “But we have to look at getting this one going first.”

Comments