ESG frameworks can still support the achievement of circularity

The concept of the circular economy has gained significant prominence in recent years as businesses, governments, and consumers increasingly recognize the environmental and economic limits of the traditional linear model. With growing concerns over climate change, resource scarcity, and waste, the circular economy has moved to the forefront of sustainability discussions. As global priorities shift toward net-zero emissions and sustainable growth, the circular economy is becoming a cornerstone of modern economic and environmental strategies.

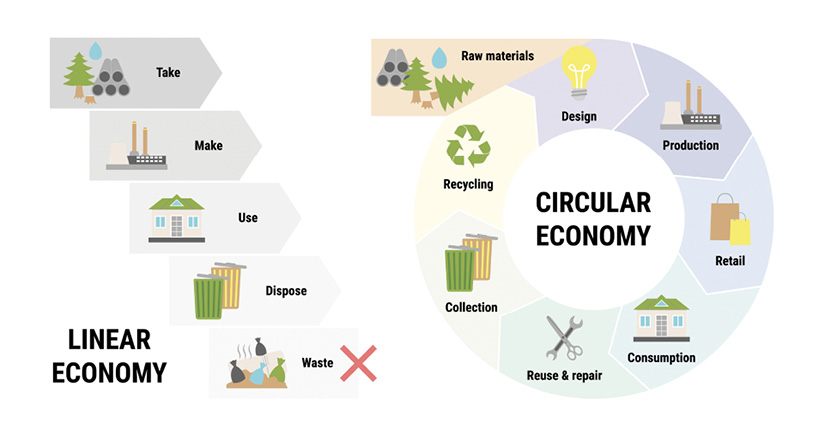

A circular economy, characterized by circular supply chains, is broadly defined as a set of closed-loop processes that prolongs the life of resources, maximizes economic benefits, and minimizes the negative environmental impacts of production and consumption. This paradigm has gained practical traction in recent years, partly because of the reports issued by premier institutes like the World Economic Forum, which suggest that the growing, global cost of climate change damage will be an estimated US$1.7 to US$3.1 trillion per year by 2050. While many industries have responded by accepting global decarbonization goals, their efforts are hindered by the magnitude of the task. Embracing an environmental, social, and governance (ESG) framework may be a partial solution to this problem.

ESG frameworks pertain to an organization’s relationship with the natural and human environment. They come with metrics, performance benchmarks and reporting frequencies, and can be voluntary or government mandated, while their roots in the financial markets mean that there can be significant socioeconomic advantages to adopting the same. In fact, ESG-oriented investing now tops US$30 trillion — up 68% since 2014. And in a survey administered by PwC Canada in 2024 of 20,662 consumers worldwide, 46% said they intentionally buy products that are more sustainable than others. This meteoric rise has been attributed to growing consumer awareness and pressures on companies to ensure the ethical provenance of their goods and sustainable (eco-friendly) manufacturing of the same. ESG frameworks, therefore, inherently support the basic tenets of circularity, which include the 3Rs for manufacturers: “reduce (minimizing the consumption of natural resources), reuse (materials and parts), and recycle (for additional value creation and proper disposal).” As such, ESG frameworks can remain a viable starting point on the path to mitigating the circularity gap with benefits to boot.

Additionally, ESG frameworks come with internal benefits too, which further incentivises their adoption and the movement towards sustainable development. An ESG-based operational approach can help reduce rising operating expenses (OpEx), which can affect profits as much as 60% according to McKinsey research. Proper ESG execution can also

- enhance employee retention and engagement, which increases overall productivity;

- reduce adverse external interventions (regulatory and/or legal), and thereby prevent the diversion of resources; and

- enhance internal investment and asset optimization. It also creates opportunities.

Mining companies, for example, may acquire social license to operate in areas previously denied to them by more effectively engaging with Indigenous communities. And as far as availability goes, ESG frameworks are widely available to be used as a potential roadmap to achieve circular strategies.

Unfortunately, therein lies a limitation of these well-intentioned tools, the sheer diversity of the same. Hundreds exist, with only a dozen major ones. In the mining sector alone (both globally and in Canada), the list includes offerings from the World Gold Council’s Responsible Gold Mining Principles (RGMPs), the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), and Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM). As such, the scoring system for E, S, and G lacks consistency, and there is debate on whether ESG principles should be risk management or impact focused. Individual mining companies can also span a range of jurisdictions, where different frameworks may apply, and process heterogeneity or organizational maturity (junior miners versus small and midsize enterprises (SMEs) versus established giants) can also render the adoption of certain frameworks ineffective. Some of these reasons may be contributing to the decreased global shift towards circularity, with a drop from 9.1% in 2018 to 7.2% in 2023 of secondary materials consumed, despite the volume of discussions on this topic having tripled in the last five years.

In the absence of alternatives, however, ESG frameworks remain a step in the right direction. The concept of circular economies is still evolving and subject to innovation: various consulting groups like SLR, IBM, and Venture have developed ESG evaluation, guidance, and adoption tools; research and development groups are formulating algorithms to quantify the circularity index in an industrial cluster, which may make data capture and reporting easier; and bodies like the International Organization for Standardization are producing protocols for global harmonization and alignment of ESG approaches (2024). Companies have also hired and/or ensured that at least one current employee/department handles work related to ESG-compliance. And so, a continued steadfast commitment to ESG adoption is warranted.

In the Canadian context, ESG frameworks, if properly leveraged, can also serve as a differentiating factor for Canadian mining on the global commodities scene. This strategic shift not only reduces environmental impacts but also enhances the long-term sustainability of mining operations by promoting innovation in areas like recycling, energy efficiency, and closed-loop supply chains. To better support the integration of ESG frameworks, entities like Cambrian College’s Centre for Smart Mining (CSM) can work with mining groups to develop clean and green methods of extraction. This is the case with the CSM’s partnerships with lithium miners, whose operations are consequently differentiated from processes abroad. Moreover, the CSM currently offers upskilling programs in Indigenous engagement designed to support organizations, companies, and corporations as they engage with Indigenous peoples and communities.

In a competitive global market, where environmental and social concerns are increasingly influencing investment and trade decisions, developing these strategies can position Canadian mining as a leader in sustainable resource management, setting it apart from less environmentally conscious competitors. While circular economy should remain the medium to long-term goal, ESG frameworks can get organizations heading down the right path.

Steve Gravel is the manager of the Centre for Smart Mining at Cambrian College, and Dr. Madiha Khan is an analytical research lead at Cambrian R&D.

By Steve Gravel and Madiha Khan, PhD

Comments