Dundee tests new frontiers for drones

Chelopech mine in Bulgaria Photo: Adam Lach

It can go to places in an underground mine where humans can’t go safely or should not go at all. It is the A3R – an advanced autonomous aerial robot, otherwise known as a drone – and Toronto-based Dundee Precious Metals is one of the first mining companies in the world to employ the technology in a sub-surface operation.

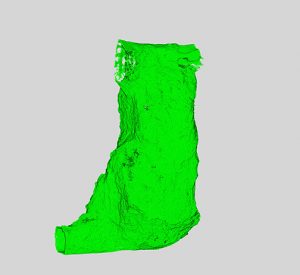

A scan of a stope, generated by the Exyn A3R in

real time.

CREDIT: EXYN

Dundee is currently incorporating the A3R into the operation of its Chelopech gold, copper and silver mine in Bulgaria.

Chelopech has been in production almost continuously since 1954 and has several thousand metres of underground workings, including many long abandoned tunnels, drifts and stopes.

“Typically you get eight guys with all the safety gear and breathing devices and they walk into these areas to inspect them.” says Theophile Yameogo, Dundee’s vice-president of digital innovation. “We’ve sent the drone into abandoned areas where no human has been for years. The drone went in and took pictures and returned. Now we know what’s there.”

That is just one of potentially many applications that will enhance safety, improve productivity and lower costs. But as an early adapter of a complex piece of technology, Dundee personnel are still learning how to use the drone and how to incorporate it into the daily operation of the mine. “It’s very new to us,” says Dundee vice-president and chief operating officer David Rae.

“We’re very excited about it and there’s lots of opportunity.”

Philadelphia-based Exyn Technologies developed the A3R by leveraging research conducted over several decades at the University of Pennsylvania’s GRASP laboratory. But the company’s

own in-house team created the proprietary exynAI software that drives the A3R. Exyn CEO Nader Elm says it is that proprietary software which makes the robot an intelligent, autonomous and potentially powerful new tool in underground mining.

“Everything you see physically is entirely unremarkable and off the shelf,” says Elm. “You could buy all the components from Amazon.”

The robot is a four-armed device with helicopter-like rotors at the end of each arm and measures about one metre tip-to-tip.

It is powered by a lithium battery similar to those found in cell phones and the on-board computer contains a standard Intel I7 dual-core processor.

Yet, thanks to the exynAI software, the A3R can navigate through an underground mine without relying on GPS, electronic markers or beacons. Mine employees do not need to communicate with the robot while it is flying and the robot does not require a map or any other advance information about the environment in which it is flying.

Essentially, the A3R contains the onboard computing power to determine where it is in relation to its environment, where it is going and how to proceed from point A to point B and back again. It relies on a LiDAR flight critical sensor, which Elm describes as similar to a laser tape measure. The sensor shoots out 300,000 points of light per second, allowing the A3R to determine its location while airborne and to build a map as it flies through the environment.

Exyn displayed the A3R at the March 2018 Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada convention, where it first came to the attention of Dundee’s digital innovation team.

Yameogo says he and his colleagues have worked closely with Exyn personnel over the past year to determine how the drone could be used underground.

The collaboration between the two companies included a test run of the drone at the Norcat Underground Centre in Sudbury and a team from Exyn spent two weeks testing the A3R at the Chelopech mine. Dundee personnel began operating the drone unaided in January, but the company is still working with Exyn on modifications to the software that will add functionality and determine the final price.

“The software is still being developed because it wasn’t native to mining,” says Rae. “We told Exyn we’ll tell you what we want and we’ll get a solution everybody is happy with. Then we’ll figure out what it’ll cost.”

Currently, mine employees are using the drone primarily to survey stopes that are either mined out or still in production in order to meet the regulatory reporting requirements of the Bulgarian government. Dundee is allowed to extract up to 2.2 million tonnes of ore per year, almost four times the volumes attained in the best years of state ownership and communist rule.

Dundee is maximizing production through the creation of large stopes, which can be up to 60 metres in height, 20 metres wide and 40 metres or more long. Before acquiring the drone, the company’s cavity monitoring system was slow, inefficient and technologically unsophisticated.

Employees known as surveyors relied on a LiDAR scanner that was mounted on a two-wheeled buggy. They pushed the buggy into a stope using a telescopic poles consisting of aluminum rods. “You don’t want to walk into a stope because it’s unsafe,” says Yameogo. “There’s rubble, unsupported walls and ceilings. Stuff could come down. That’s why it’s a human-denied environment.”

A survey of a single stope could take up to four hours to complete and the LiDAR generated a three-dimensional image containing some 50,000 data points. The A3R can complete a scan in two minutes and produce an image with up to 50 million data points, or 1,000 times more detail. “The density and clarity of the imaging is vastly superior,” says Yameogo. “It’s night and day.”

Surveyors transport the drone underground in the back of a pickup truck. They send commands via laptop or tablet to launch the drone and Elm points out that missions can be either planned or exploratory. In a planned mission, such as stope surveys, operators instruct the A3R to take off, ascend to a certain height and then fly straight ahead. Once airborne it flies autonomously and, thanks to the software embedded inside, it finds its own way in and out of a stope. The drone can also fly exploratory missions, in which operators launch it and it flies without any pre-determined parameters other than to fly a certain distance and return to the point of origin. “If it’s a drift, you can tell it to go 150 metres straight ahead and come back,” says Elm. “In a room and pillar mine it can go and explore galleries, go around pillars and map without any human intervention.”

Dundee has built a sophisticated and comprehensive underground Wi-Fi network at Chelopech, in part by employing technology developed by its own wholly-owned subsidiary Terrative Digital Solutions. The network allows mine employees at surface to observe the drone on their laptops as it is doing its aerial surveys.

“You can see the mapping on a tablet in real time, which is really compelling,” Elm says. “Folks who watched it are completely silenced by it.”

Rae adds that for three hours a day, while blasting is being done, nobody is working underground. But the drone can still be flying to conduct one mission or another. “We’re utilizing time we’re not currently using,” he says.

Apart from operational efficiency, the A3R can contribute to health and safety. “In an underground mine you have health and safety guys walking the mine at all times just to check things,” says Yameogo. “With the drone, they can do some of their work from an office at surface. Fewer people underground makes the mine safer.”

And Dundee is just beginning to tap the potential uses of the technology. In the future, Dundee may be able to mount sensors to detect or monitor air quality, among other things.

“We don’t know where it ends,” says Rae. “This is just the start.”

Comments