The cleaner, drier future of mine waste

An FLSmidth 4-metre by 2-metre pressure filter. The company is working with Goldcorp on developing EcoTails technology and will offer the system commercially once testing is complete. CREDIT: GOLDCORP

The numbers are a mine owner and manager’s worst nightmare. Ten million cubic metres of water and 4.5 million cubic metres of slurry pouring from a 4-sq.-km sized tailings pond into Polley Lake, raising it 1.5 metres. Hazeltine Creek transformed from a 2-metre-wide stream to a 50-metre “wasteland,” according to local press. Along the way, trees ripped from their roots amid a torrent of mud and debris flowing as far as Quesnel Lake and Cariboo Creek.

That in a nutshell is what drove the work and findings of a panel examining Imperial Metals’ tailings dam collapse at Mount Polley in August 2014. The causes, they concluded: A history of operating the pond beyond capacity and failure to correct an interim design measure which steepened the angle of the dam’s slope, and a “trigger for the collapse” said panel chairman Norbert Morgenstern.

But the real culprit, said the report, was the mine’s original design. “The design did not take into account the complexity of the sub-glacial and pre-glacial geological environment associated with the Perimeter Embankment foundation.”

That layer of continuous GLU glacial till, unaccounted for by the original engineering contractor, was also undetectable by government inspectors who could not have recognized, said the report, “that it was susceptible to undrained failure when subject to the sresses associated with the embankment.”

It’s all in the design… or should be

Today, Cam Scott, principal geotechnical engineer for SRK North America, says the viability of a mine’s tailings facility can’t be separated from recognition of the mine’s design at one very crucial stage.

“You need to go into design thinking about closure and having a closure plan in place. It’ll probably be refined over time, but that’s the number one significant thing in my view,” Scott says.

The Mining Association of Canada (MAC) also made it clear in a revised Tailings Guide released in November that it wants more attention paid to “minimizing harm,” i.e. “zero catastrophic failures of tailings facilities, and no significant adverse effects on the environment and human health.”

“It’s a tall order, isn’t it?” replies Scott. “I absolutely am certain that the bar is being raised yet again and that the likelihood of getting there is higher and higher as time goes on.

Will we get to zero? That’s certainly the hope.”

MAC’s Tailings Review Taskforce has made numerous updates to the tailings guide to help industry get closer to zero, stressing the importance of assessing and selecting Best Available Technology and Best Applicable Practice. That includes new technical components critical to the physical and chemical stability of tailings facilities, something Scott helps unpack.

“I think it comes down to two fundamental issues: geochemistry and physical stability. On the physical side it’s very much about managing the solids and the water. And if you can’t control the geochemistry then you have to be able to manage the water.”

Trafficable and stackable

Water has been the underlying source of virtually all failures of tailings storage facilities, making water recovery the key to tailings design and mine operations. Decades ago, slurries were simply discharged from a mine site into the surrounding environment with little thought given to their impacts. Enter new ideas like cyclone sand placement which recovers roughly 25% of water, conventional thickening and paste systems at 60% and 70% of water respectively, all the way to the extremely costly physical filtration systems which can recover as much as 80-85% before the remaining material is taken away by earth-moving equipment and dry stacked.

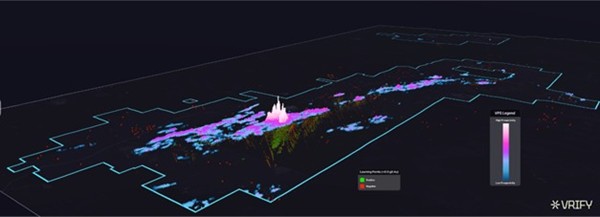

GeoWaste test piles at the Peñasquito mine in Mexico, where a proof-of-concept study on EcoTails is under way. CREDIT: GOLDCORP

Use of these technologies naturally depends on how they’re applied and the surrounding environment, but can we do even better? Simon Hille thinks we can. The vice-president of Technical Services, Metallurgy and Process at Goldcorp is on a mission with Mike Jacobs, director of Water and Tailings to not only drastically reduce fresh water consumption and reduce the footprint of mining operations but also to eventually eliminate conventional slurry tailings, currently the largest store of unavailable water in the mining process.

The centrepiece of Goldcorp’s Towards Zero Water (H2Zero) initiative is Eco Tailings, award winning technology designed to improve tailings and waste rock disposal while processing mine waste and increasing water recovery. Part of this involves building a “trafficable” process system, says Hille.

“We dewater to a conveyable moisture point. What we then do is blend that dewatered tailings product with waste rock on a conveyor in flight to create a product we call GeoWaste.”

This sounds like traditional co-mingling but the difference maker, says Hille, is science. Where traditional co-mingling places two products side by side and blends them together using heavy moving equipment, “we’re trying to reach a certain core filling of the particles so that we create a product that will both be pliable and reduce the potential for oxygen to enter these pilings in the future.”

The remainder can then be terraformed and progressive closure techniques applied “so that what we leave behind is being closed while we’re still in operation and is not something simply left for the future.”

Hille is currently overseeing a proof-of-concept study of the system at Mexico’s Peñasquito polymetallic mine which he hopes to complete this summer. Goldcorp expects this to be followed by a full-scale prototype and, fingers crossed, actual mine deployment.

Considering cost and risk

Air drying large tonnages requires significant amounts of time, multiple units and high energy use “to blow that water down,”

Hille added. This can account for up to a third of the cost of filtration.

A simple “fast filtering” process to deliver a conveyable moisture product like GeoWaste eliminates the need for that blow down stage, he says.

Can Goldcorp scale up Eco Tailings to high volumes to make it cost-competitive against the industry standard? It says it can, but to do so will require processing equipment up to 375% larger than what is currently on the market to lower operating costs and streamline maintenance. The goal at the end of the day: No tailings dam, lower fresh water use, reduced acid rock drainage, smaller mine footprint and less overall risk.

That last item is like gold to Andrew Watson, sector leader for mining at Stantec in Denver, Colo. Watson has published and presented numerous times on managing tailings storage facilities at mines, seeking practical solutions to engineering challenges using risk-based decision-making. It’s driven by a number of risks.

“What’s the physical risk of having wet tailings stored behind an impoundment or dam and do we actually have the water to operate the facility? If we can recover the water and recirculate it, we’d be in much better shape.”

Those paying particular attention are financiers and investors who base their assessment of the properties they’re interested in on what you have to say about potential liabilities. “What do they need to see in order to evaluate a property? Because if you can’t address that then they have to put their own safety factor on what they’re prepared to pay,” says Watson.

Remain silent on risks such as those posed by weak tailings design and operations and the prospective buyer or financier “is going to put their own spin on it and make an offer commensurate with their own risk evaluations,” he adds. Address those issues yourself and allay people’s concerns, and they might pay you a little more.

And then there’s the industry’s own bottom line. Risk based decision making is not aimed solely at squaring risk to people and property with short term profitability, Watson explains.

“People are realizing it’s great if you’re going to make a lot of cash in the first few years but it doesn’t help you if you start giving it all back again.”

Watson says we already have a model for avoiding zero catastrophic failures like the one at Mount Polley in the model for zero harm to workers. “If we adopted a similar approach and applied the same tools and training and monitoring that we do for work safety around our environmental performance we could lick this.”

The eventual goal, Watson adds: to convert all the potential energy contained within a tailings facility “so that you don’t have to carry this big contingency on your books. Millions of those dollars are on company balance sheets right now in order to account for future obligations.” And the added costs in new facilities like that proposed by Goldcorp?

“I think this goes back to Cam Scott’s point: you need to think about these things as you’re conceptualizing the whole deal,” Watson says.

Unless you can justify the trade-offs at the beginning, it’s awfully difficult to proceed to a more advanced takings technology.

“If you’ve already spent a hundred million dollars on a storage facility and then say you don’t want to use it is a drastic change of course,” he adds.

Getting everyone in the room

Something that may help, Scott said, is contained in MAC’s 29 recommendations for tailings management, including a framework for annual inspections, audits and the push towards an independent review panel. “It’s not perfect, but I think it’s good to have a completely independent set of eyes asking the questions, challenging the designers and the engineer of record.”

Watson agrees. Imagine two people in a room he says, one the mine owner, the other the mine’s chief engineer. They’re at cross purposes as to how much they should spend and the level of care that’s required on the tailings end of operations. Having a third voice in the room like an independent engineer could make all the difference by “slowing the conversation down a bit,” Watson says.

“That independent engineer could do two things: talk sense to the owner in terms of how to manage their risk better and talk sense to the engineer in terms of making sure they do the right thing. One of the biggest benefits is that you get a cross pollination of ideas and best practices.

Comments