Canada’s first mining scandal

Most mining industry insiders remember the Bre-X scandal of 1997 as Canada’s, and possibly the world’s, worst case of stock and mining fraud. It was certainly a big deal, featuring geological samples salted with gold, the suspicious death of a geologist, a raft of lawsuits, non-stop national news coverage, and a speculative stock frenzy that accompanied the company’s false proclamation of the biggest gold find in the world at Busang, East Kalimantan, Indonesia. More than two decades later, the name Bre-X is still synonymous with the greed and dishonesty that has tempted some in the mining industry to “game” the stock market by misrepresenting the value of mineral strikes.

Such cases are rare in the recent history of Canadian mining, but there are examples from the very early days of the industry. Indeed, the very first European mining project in what we now call Canada, Martin Frobisher’ journeys to the eastern Arctic from 1576 to 1578, deserves a prominent place alongside Bre-X in the history of mining scandals.

Frobisher organized his first journey to the eastern Arctic in 1576, not to find minerals, but to unlock the northwest passage to China. Things went badly from the beginning, as one of the three ships on the voyage sank and the other turned back to England after a violent storm. Faced with an indiscernible maze of water and land near Baffin Island, Frobisher failed (like so many others would) to find a way through. So, he started looking for other ways to justify his voyage, grabbing ore samples from Little Rock Island, a tiny land mass of the southeast shores of Baffin Island. He also kidnapped an Inuk, who later died of illness, in retaliation for the mysterious disappearance of five of his men when they took a potential Inuk guide to shore. Upon Frobisher’s return to England, his financier and promoter Michael Lok sent the rock samples for assay. While three of the assayers pronounced it worthless, a fourth, Giovanni Batista Agnelli, suggested that his samples contained gold.

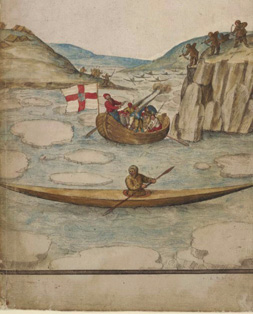

Inuit and Frobisher’s men. The painting was

produced between 1585 and 1593 as part of a

book of 113 drawings. THE IMAGE IS PRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM FORMAC LORIMER BOOKS

A full-scale gold rush to the eastern Arctic was not feasible in the 16th century, but Frobisher and Lok were able to mobilize enough capital to finance a new expedition. Lok founded a joint stock venture, the Company of Cathay. Among the many investors, Queen Elizabeth funneled £1000 toward the venture and loaned a ship, aware of the riches the Spanish royal court had reaped from New World mining operations in Mexico.

Frobisher’s fleet arrived in the Baffin region in July 1577, disappointed not to find a large deposit of gold-bearing on Little Rock Island. They did find remnants of European clothing in an abandoned Inuit camp on the southern shore of Frobisher Bay. Assuming the men had been murdered and cannibalized, Frobisher organized an attack on a nearby Inuit camp, killing five Inuk and getting wounded in the rump by an arrow. The exploration party eventually found a large deposit of what Frobisher thought was gold-bearing rock on Countess of Warwick Island (today Kodlunarn Island). By August, Frobisher’s crew had picked away about 200 tonnes of ore using hand tools, which they transported back to England along with three Inuit captives who did not survive for long.

Once again most of the assays suggested that the ore contained no gold. The assayer on the voyage, Jonas Schulz, had claimed the ore contained 2.6 oz. of gold per tonne, but the results may have been compromised due to Frobisher brandishing a knife to speed up the work. Back in England, one assayer, Benjamin Kranich, reported that the ore contained a jaw-dropping 13.5 oz. of gold and 50 oz. of silver per tonne, but his assistant warned that Kranich had added silver and gold to account for the small size of the sample.

This one questionable assay was enough to mobilize investors to fund a third voyage, a large fleet of 15 ships that departed for the Baffin area in June 1578. The expedition was supposed to probe more for the northwest passage and build a colony for 100 crew members to stay through the winter (an experiment to determine if they could survive). They failed to achieve either goal, befuddled by the geography of the Arctic Islands and loathe to leave men behind after the supply ship containing housing material and a winter’s supply beer had sunk. The expedition crew did manage to build the first English house in the Americas, though nobody ever lived in it. More impressive was the haul of ore, as the crew managed to load 1,350 tonnes on the ships and carry it back to England.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Lok had convinced investors to finance construction of a smelter in the town of Dartford. When the ships arrived, weighed down with ore, there must have been great anticipation through the fall of 1578 while workers wheeled cart after cart of stone up to the smelter. But repeated attempts at smelting produced no gold or silver. While angry investors and company officials at first blamed the assayer, the adage to not shoot the messenger eventually held sway. The rock was worthless, with some of it eventually used to erect a fence at a royal property in Dartford, where it can still be seen today.

If the Queen recovered a small portion of her investment, other investors were left high and dry – and extremely angry. Lok ended up in debtor’s prison over the Baffin misadventure, while Frobisher re-focused his energies on a naval career. Neither man can be accused of actively contaminating ore samples and walking off with the stock proceeds, as in the Bre-X case, but they did misrepresent the value of their ore, raising investment capital for their adventures based on fraudulent pretenses.

Business fraud is certainly not unique to the mining industry (witness the recent allegations against crypto entrepreneur Sam Bankman-Fried and the recent conviction of medical device fraudster Elizabeth Holmes). But fraud did occur as mining expanded in North America, the temptation of quick riches often luring investors into dubious mining schemes. During the golden age of mining in the western United States, Mark Twain opined that a mine was nothing more than “a hole in the ground owned by a liar.” Twain’s rhetoric may be unfairly broad, but there is no doubt that Frobisher, as the first European mining entrepreneur in North America, was one of those liars. Even though the Baffin voyages occurred over 500 years ago, Frobisher’s fraudulent actions and destructive relationships with Inuit left a legacy that invites no small measure of reproach in the present day. CMJ

John Sandlos is a professor in the History Department at Memorial University of Newfoundland and the co-author (with Arn Keeling) of “Mining Country: A History of Canada’s Mines and Miners,” published by James Lorimer and Co. in 2021.

Comments