Cama celebrates 25 years

The Ring of Fire panel at CAMA’s 25th annual conference in November. CREDIT: STAN WESLEY

The Canadian Aboriginal Minerals Association was formed in 1992 to give voice to community concerns around mining, and to bring the two parties together. In fact, CAMA cofounder and president Hans Matthews – who is also a geologist with experience in exploration and mining – describes the organization as providing the services of both a “dating game and marriage counsellor.” While there’s been a lot of progress in the relationship between the mining sector and the Aboriginal community over the past 25 years, with the number of agreements, including IBAs, growing to over 400 from only six, and greater understanding of each other’s objectives on both sides, there’s still a ways to go in the evolving relationship.

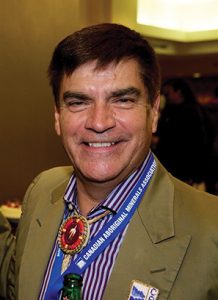

Hans Matthews

Community concerns around water and the environment are increasingly overshadowing the economic benefits that mining can bring – as reflected in CAMA’s recent conference in Toronto. CMJ spoke to Matthews in late November about this and other trends.

CMJ: The theme of this year’s conference was water – why did you choose that theme?

Hans Matthews: When we meet with mining companies and communities, the key focus of the communities’ concerns are about water. I think the days when people were screaming for jobs, jobs, jobs, that’s taking a second or third seat down compared to what communities are desiring today, which is prudent or effective environmental management. Also from last year’s conference, a lot of youth and elders were saying we have to protect the water because we all need it whether we’re a mining company or an Aboriginal group.

We try to differentiate ourselves from other mining associations because we’re not trying to advocate for the mining industry, we’re focusing on sideline issues that few want to address head on like water, or social and mental health in a community.

You won’t find a mining conference where they have elders who have been through residential school and they want to share their story. So it’s educational for mining companies to be exposed to all of these other facets in community life. It helps the company understand how to move forward.

CMJ: I think that the mining industry is talking about water more, they do recognize its importance to communities, I think – so do you see some common ground there, potentially?

HM:I think there’s a transition occurring in the mining industry where there’s a big group who still go by the philosophy of solution by dilution: to get rid of effluent from a tailings pond or a mine, some companies will do the bare minimum treatment and flush it out into the environment to mix with existing rivers and lakes. We’re trying to avoid that.

CMJ: So there’s part of the industry that still has that attitude and then there’s another part of the industry that’s more progressive?

HM: I think we’re reaching a point where companies are getting more committed to being innovative in environmental management. The next push will come when they actually involve the aboriginal community in that discussion.

We’re at a stage right now where aboriginal communities in some regards are still considered checkboxes on the way to get the permits and government approval, whereas it should be the other way around where the companies should be working with communities to develop plans jointly and gain the approval of the community. The approval of the federal and provincial governments should be secondary.

CMJ: How do mining companies respond to the idea of having Aboriginal communities more integral in closure planning and environmental assessments?

HM: I think they’re skeptical because they’ve always hired some of the larger environmental firms in the hopes that if a major, multinational firm rubber stamps their own work and submits it to the government that it should be a cake walk – we can check that off the box and then we can go ahead.

To many companies, the limit of aboriginal involvement is with traditional ecological knowledge – to include that in the environmental assessment. It’s unfortunate, but it’s still a checkbox approach. To give you an example, when a sacred site is found, some companies will just say ok, we won’t do any development within 100 metres of it. So it’s not put in the context of respect – the community wants to protect the site, it’s not just about a numerical outline.

The other big area is when companies hire major consulting firms for their EAs, often the consultant or the group takes an arbitrary circle or a linear approach to outlining the areas that will be affected by a mineral development. But what communities are saying is no, no, it has to be the watershed, it has to be all of the water that’s going to be affected, that has to be included in the study. So there’s a debate because obviously depending on the size of the watershed, it can actually cost a company significantly more for a broader scoped study than say 1 km around the mineral project or development.

So there’s still conflict on how environmental management and assessment proceed, and the reason why there’s that conflict is because there’s still a misunderstanding in terms of the significance of the land. To mining companies, the significance of the land is their acreage for the tailings management area, their waste rock piles, their mill buildings, roads and so on. But to a community, the land is more important, it’s the interconnectedness of the plants, the animals, the water, the air, the soil and how these things interact to provide life and support the communities. Especially those in the northern or remote parts of Canada who depend more heavily on subsistence.

CMJ: You mentioned at the conference that there’s been a lot of progress between the mining industry and Aboriginal communities in Canada, but what’s the most urgent issue now, what’s the next area where there needs to be progress?

HM: There’s still an outstanding issue of unfinished business.

Basically, the agreements that were struck 100 plus years ago – the treaties – have been misinterpreted or ignored by governments in terms of approving and moving forward with mineral projects. And this will come back and bite the Crown for not complying with the spirit and intent of a treaty. The main thrust of a treaty is the doctrine of sharing and there’s a high-profile case that’s ongoing today called the Robinson- Huron Treaty Annuity claim: since the late 1800s, 21 First Nations (in Ontario) have not received a share of mining and resource revenue even though the commitment is written in the treaty. That’s just one example.

Another issue is areas where there are no treaties, where governments and communities and industry are wrapping their heads around “how do we move forward with approvals for projects when there’s no agreement with the Crown.” But the big area that I think we’re going to be focusing on that I mentioned earlier is that one day there will be an Aboriginal-driven environmental assessment process, where the communities will oversee the process instead of being third-tier reviewers after everything is written in an extensive half-metre thick document that the government requires them to review it in 45 days.

The other one that’s becoming very popular is revenue sharing, whether it be revenue from taxes – and this relates also to the Robinson Huron treaty – whether there’s going to be a share of revenues received by the government from mining. And the other one is revenue sharing directly from mining companies which in some respects is already occurring with some communities.

CMJ: At the CAMA conference, you also mentioned an interesting cultural difference or difference in philosophy that affects the relationship between Aboriginal communities and mining companies. You made the observation that corporate decisions are made on a top-down basis while aboriginal communities use a bottom up approach. So how can the two parties bridge that gap?

HM: Our view is that community leadership plays a significant role in being the spokesperson for the community.

But more significantly leadership often excels in facilitating – bring the community together to discuss important issues and to reach consensus and to make decisions affecting the community. Community leadership has in many cases helped the community find out more about a mineral project or participate in decisions regarding a project.

The other thing is we respect leader-to-leader communication, but negotiations should be community driven, not driven by leadership. One of the biggest complaints we’ve received from the mining industry is, “We sent them a letter and it took them two, three months to respond to it.” The reason why was the leader who they wrote to had to consult with his council, and the council had to take it to the community if it was a significant issue. So depending on the size of the community, if it’s a couple hundred vs. 30,000 and depending on the magnitude of the issue, it could take a long time to come up with a decision. Community leadership rarely make decisions on their own without consulting their community membership or other people who are affected by the project.

CMJ: So companies are expecting that communities are structured and work the same way that a company works when that’s not the case?

HM: That’s right – it’s a total illusion. In the early days of CAMA many from industry used to think, “Well we can take the chief out for a nice dinner and we’ll get the buy in and we’ll check that off the box – met with chief, he supports the project – ok, let’s go. And then all the shovels are in the ground and everything’s going and all of a sudden there’s a blockade. So to do it properly is the most effective way and if you’re a mining company executive and you depend solely on consultation with the chief, your investment is at risk. A key structure to follow is leader to leader, manager to manager and staff to staff dialogue with all three levels acting at same time.

CMJ: What else would you advise from the mining company side, or is it just the understanding of how a community actually works?

HM: The first thing I suggest to mining companies is be open and be explicit that you are committed to having a relationship, however that might be, with the local communities.

Placer Dome had a policy that said, “We recognize that our projects are on Aboriginal lands, therefore we believe that we have to involve and be involved with the community,” etc.

That was unheard of. There are other companies who have other reasons or drivers for why they should work with Aboriginal communities near their projects. Some other policies allude to creating wealth rather than respecting the community’s connection to the land. Some say that: “We recognize that Aboriginal people are disadvantaged, therefore, we’re going to work with them to improve their lives.” There’s a big difference there.

CMJ: It sounds like communication is the key.

HM: Definitely communication, but also it’s a paradigm where in the past mining companies never had to deal with anyone other than the federal and provincial government.

That’s where they got their blessing, but nowadays, that’s not the blessing that you need. The blessing that you need is with the Aboriginal community.

CMJ: Have you seen examples of companies doing it well?

HM: Some of them are doing well locally. The global companies have pockets of success but it’s unfortunate that it’s not uniform because it’s going to come back to haunt them.

I’m getting communities saying did you hear about that spill over in Brazil or elsewhere by that company, the same one that wants to deal with us? So with the internet, communities can find out everything about a mining company in minutes.

CMJ: When you look back on the last 25 years, what are you most proud of accomplishing through CAMA?

HM: Happy, smiling faces. It gives me joy at a conference to see people talking, laughing and being happy. You can see that we’ve set sort of the stage for them to interact and try to accomplish something to their mutual benefit. We don’t measure our success in dollars and cents, we measure our success in how many people are working together. Through our events we are nurturing Aboriginal community and mining company relationships … successful dating.

Comments