Building a business case for OTR recycling: Turning waste mining tires into value

The mining industry is one of the biggest global users of off-the-road (OTR), or earthmover, tires. As a consumable product, these items have traditionally had a linear make-use-dispose trajectory, with few options for refuse or reuse. However, the enhanced focus on mining companies’ environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance in recent years has shone a spotlight on their waste management practices and the possibility of building greater circularity into business models. This, combined with impending regulation in various mining countries is pushing organizations to take another look at the possibility of tire recycling and how they can make a case for it.

There is a common misconception that tire recycling is just an additional operating expense, one that companies would rather not shoulder when margins are already squeezed by low ore grades and high energy and labour costs. But, by demonstrating leadership in this area, there is a chance to generate significant social, environmental, and reputational value while helping businesses towards their near-term goal of carbon neutrality and, in the long term, zero waste.

How many tires?

While there are no aggregate figures for the quantity of used OTR tires generated globally, by examining the tonnages imported annually in key mining markets, it is possible to get a feel for the level of risk and opportunity.

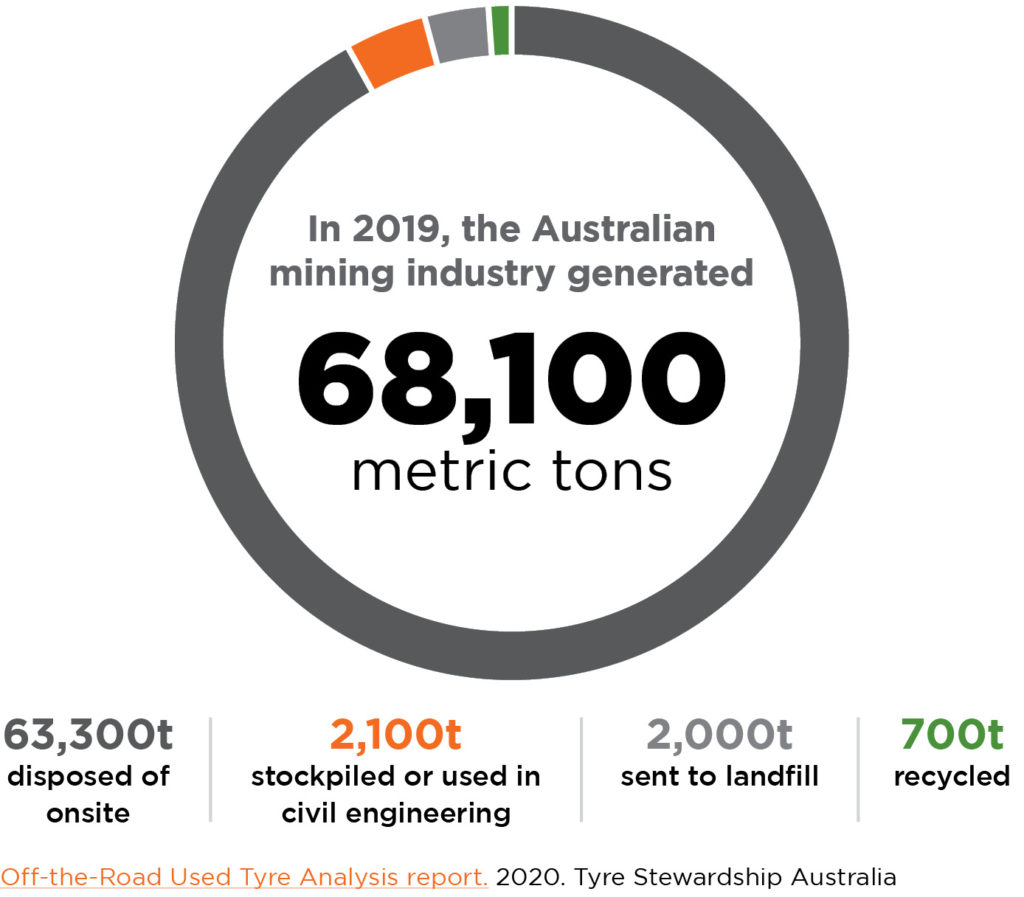

According to Tyre Stewardship Australia’s 2020 Off-the-Road Used Tyre Analysis report, the Australian mining industry generated 68,100 tonnes of used tires in 2019. Of that number, 93% or 63,300 tonnes were disposed of onsite, i.e., piled up or buried; 3% were sent to landfill (2,000 tonnes) and just 1% (700 tonnes) were recycled; and the remainder stockpiled or used in civil engineering. In the five years from 2014 to 2019, Australian mines collectively (including metal and non-metal mines) generated 315,500 tonnes of used tires.

It is a similar story in other markets. Chile hosts six of the 10 largest copper mines in the world and an estimated 500,000 tonnes of used OTR tires. Australia and Chile are just two mining jurisdictions among many. Mines are long-life operations, and some have commercial lives spanning 40+ years. This means that there are likely millions of tonnes of used tires at mine sites across the globe.

Dan Allan, senior vice-president of Kal Tire’s mining tire group explained: “There are huge quantities of OTR tires awaiting final deposition at mines around the world. At some sites, the stockpiles are so big that they are visible using tools such as Google Earth.

“Finding management solutions is difficult, because very few recycling facilities can handle mining tires. Some ultra-class products weigh approximately five tonnes apiece, so they require specialist lifting equipment and transportation, in some cases, over long distances to reach the facility, and then dedicated shredders to reduce their size.

“Even in places which have recycling mandates for OTR tires, often the firms that are authorized to collect the tires are challenged with this because of the cost and logistics involved. They would rather collect passenger tires because they are easier to handle.”

Although used OTR tires are, in most mines, simply buried or used to create final landforms upon closure, some companies are doing the best they can to repurpose them in the interim. For instance, cutting the tires in half and using them as safety berms along haul roads, or passing them to agricultural neighbors to use as cattle feed troughs. However, the problem remains that tires do not degrade. While their component materials are chemically inert, regardless of whether they are onsite or sent to landfill, those tires will remain in the landscape indefinitely.

The passenger and on-road truck tire markets are further ahead in recycling, both in terms of supply chain maturity and uptake. These products are routinely shredded and used as tire-derived fuel, or turned into rubber crumb which can be repurposed, for instance, in asphalt or infrastructure projects.

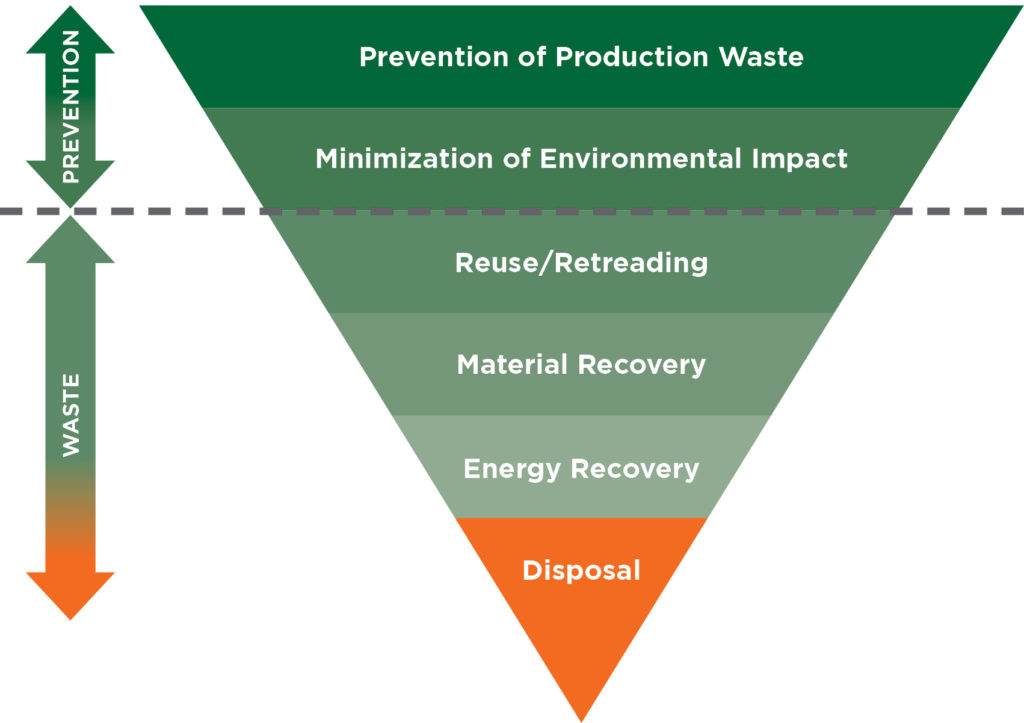

“Shredding is better than burying tires but, ultimately, it is just delaying their journey to landfill,” said Allan. “The world only needs so many tires in playgrounds or lawn mulch, and it really does not need any more oil-based products to be burnt.

“We should be seeking out the highest and best uses for these materials. By breaking tires down into their fundamental elements (carbon black, steel, and petroleum-based products), we can reuse them to create new tires. That is the optimal use, because it provides a substitute for new carbon products and helps to reduce their total carbon footprint.”

Circular by nature

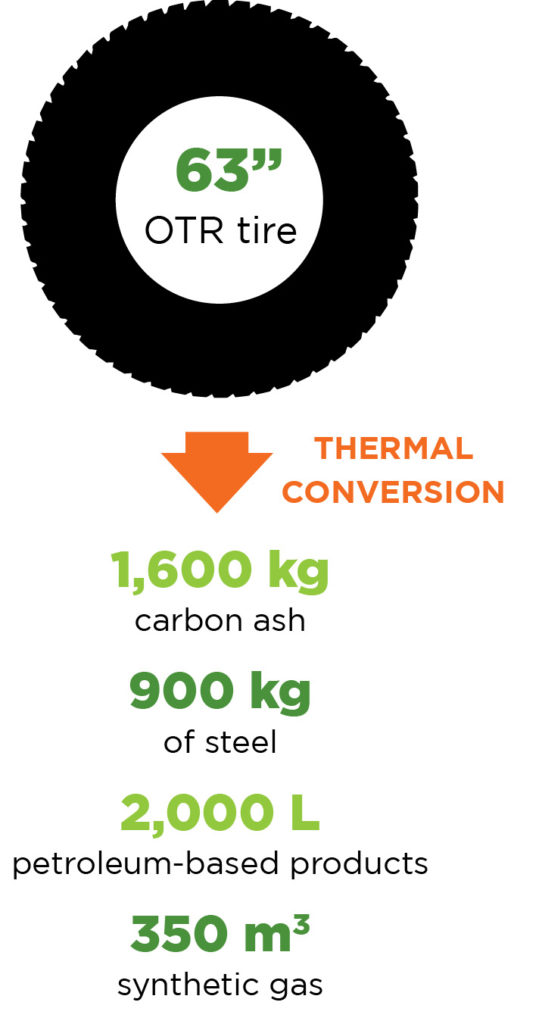

Breaking down a 160-cm-diameter radial OTR tire using thermal conversion or pyrolysis would produce approximately 1,600 kg of carbon ash, which can be upgraded and used as a replacement for new carbon black. It would also produce 900 kg of high tensile steel and 2,000 liters of petroleum-based products which can be refined and used to create new tires, and 350 m3 of synthetic gas that can feed the recycling process.

Elevating awareness through ESG

While waste tires are chemically inert, there are still risks associated with storing them. The shape of OTR tires means that their insides are cavernous and prone to holding water which can attract creatures, like spiders and snakes. If those tires need to be moved at any point, they could pose a safety risk to employees. Tires are also flammable, and tire fires can be hard to control and extinguish if an incident were to occur.

But the biggest risks (and opportunities) are ESG related. Investors, stakeholders, and landowners are becoming increasingly interested in the way in which mining companies steward the land. While mining organizations are not yet required to disclose the quantity of used tires held on site and the way in which they are managed, ESG metrics and disclosure tools are developing rapidly. In time, outdated practices, such as burying tires, could pose a reputational risk for a sector whose environmental and social performance is increasingly under a microscope. And, as a very visible form of waste (even buried stockpiles need to be marked in certain jurisdictions), used tires may also make mining companies a target for disgruntled environmental groups and protestors.

Ontario, was one of the first major mining destinations to introduce a tire recycling legislation in 2016. However, this mainly centers on shredding and repurposing the rubber. There are also voluntary initiatives in other Canadian provinces. For example, Kal Tire’s mining tire group has partnered with Liberty Tire to offer shredding services for earthmover tires across western Canada. South Africa also has a waste tire recycling program under which a levy is imposed on newly purchased tires to fund recycling, but manufacturers have indicated that the system there has problems which have led to tires being stockpiled.

Chile has recently introduced legislation which specifies that starting in 2023, 25% of mining tires must be recycled, this increases to 75% as of 2027, and to 100% as of 2030. To enable this, Kal Tire’s mining tire group opened an OTR tire recycling facility in Antofagasta in 2021 which can handle up to 20 t/d of tires, including ultra-class products. The company has developed a unique thermal conversion process that uses heat and friction to convert the tires back to their base elements (100% of the material can be repurposed) and there are no harmful emissions. The solution is scalable and could be replicated in other mining markets.

Australia looks set to be next; Tyre Stewardship Australia recently received a federal government grant to deliver a business case that will improve OTR resource recovery in various sectors, including mining. The final report is slated for delivery in March 2023.

Regulations such as these are a step in the right direction. However, they are only applicable from the date of introduction. Many mines will have operated prior to this and built up a stockpile of waste tires and/or could find themselves exempt due to incumbent regulation at the time of permitting.

While it is unlikely that buried tires would ever need to be dug up, as more legislation is introduced, mining companies will need to evolve their used tire management and mine closure practices to be compliant.

There is also a question of reputation. Companies that operate in multiple jurisdictions are expected to apply the same high standards and best practices to mines in unregulated jurisdictions as they would to those in regulated ones. In doing so, there is a chance for them to stand out as ESG leaders and to raise the bar for the industry as a whole.

Finding the funding

The desire for change is real, but the question remains of how to pay for it? Regardless of the chosen recycling method (pyrolysis, devulcanization, cryogenic etc.), the recycling of OTR tires is costly and, if there is no regulation, mines can struggle to make the case for capital allocation.

Allan explained: “One way to tackle this is through accessing mine remediation budgets. Every mine has money set aside for reclamation and eventual closure. The challenge lies in accessing that budget today, so that mines can recycle tires progressively rather than waiting until closure when there are thousands of products awaiting disposal. There’s an evolution that should happen internally to bring those two value streams closer together.”

Regulators across the globe are also starting to support this thinking. In April 2022, the government of British Columbia, introduced an interim reclamation security policy for the mining industry which requires that reclamation liability cost estimates include both conventional reclamation (such as resloping and re-vegetation) and environmental liabilities (such as water treatment). The policy also requires bonding for specific liabilities, and actively encourages progressive reclamation throughout the life-of-mine consistent with industry best practices to reduce site liabilities, closure timelines, and ongoing monitoring requirements. By taking a proactive approach to OTR tire recycling as part of this, mining companies have the chance to better their stance as environmental stewards and boost their standing with stakeholders.

Carbon taxes are also on the horizon. In the places which currently have recycling legislation for OTR tires, retreading or extending the operating life of used tires is an integral part of the process. Some companies may be able to use that practice to garner carbon credits which can (through cap-and-trade agreements) help to offset the cost of recycling.

Allan added: “The carbon trading landscape is still evolving. However, it is possible to see how retreading and recycling could potentially be harnessed to create a carbon-positive effect. For example, Kal Tire’s Maple Program uses a third-party accredited carbon calculator to quantify and reward mining companies for the oil and carbon emissions they save by using its Ultra Tread, retreading and Ultra Repair services.”

Greater uptake of recycling can also drive social prosperity. Through committing to recycling and building partnerships with Indigenous or First Nations businesses to create reliable and sustainable supply chains, mining companies have the chance to boost the local skills base and technological capabilities and leave a positive legacy for the communities in which they operate.

“By seeking out the highest and best use cases for these materials, companies can create a virtuous circle,” said Allan. “Because carbon does not degrade, OTR tires can provide a source of carbon black which can be used to reduce pressure on primary production. Approximately 18 billion pounds (8.1 million tonnes) of carbon black is produced worldwide each year, and 90% of that is used in rubber applications. Imagine the impact the mining industry could have on the circular economy if it worked to turn its waste tire stream into a source of value.”

Working together to generate value

Ultimately, a diverse approach is required to boost the uptake and accessibility in OTR tire recycling. This includes government-led policy, standards (to ensure safety and quality in the collection and recycling process), proactive investments from mining companies, technological and product innovation from tire manufacturers, and willingness from local businesses to build the skills and capacity required to turn these “waste” products into a source of value. That change necessitates openness, communication, and collaboration across the complete value chain.

“To enable this transformation, mining companies should find ways to build bridges from their boardrooms to the mine sites, to raise the visibility of this issue, and to help teams to access remediation budgets,” Allan concluded. “Companies might consider ways to access those funds to meet today’s reclamation needs – they do not need to wait until year 25 to begin turning their waste tires into value.”

Comments