Bioreactor red flags and realities

Toward a better understanding of bioreactors in the mining sector

I typically stand on my soapbox advocating for bioreactors to be used more across the mining sector (and they really should be), yet here I find myself writing this article in the hopes of putting some of my services out of work — specifically, fixing broken bioreactors. Over the past decade and a half, fixing bioreactors has provided me and my companies, formerly Contango and now Maven Water and Environment, with a nice business line, but I would much rather focus my talents on advancing and creating technology. Yes, mining needs more bioreactors, but we need good ones.

Despite my many successes in developing new biological water treatment technologies for the mining sector, I still find myself picking up the phone to deal with predictable and often familiar stories repeated in different places with different people asking for help with bioreactors that “do not work”.

Yet, much of what I am called upon to “fix” was never “broken” and is not bad technology. Rather, it was just not implemented in the right way. Most of these issues come from trying to implement municipal wastewater bioreactors to treat mine-impacted waters. I will only say this once, so pay close attention: mine water is not municipal wastewater. It feels a bit silly to have to say that, yet I continue to encounter bioreactors that are designed and operated based on municipal wastewater designs found in old engineering textbooks.

I find it worrisome that, despite the advances in technology and the growing number of experienced and qualified professionals in the water treatment sector who could design and operate a bioreactor, the calls about broken bioreactors are increasing. Here are some of the familiar themes in these calls:

“A bioreactor was designed and built, but …”

> It was never commissioned to meet the design criteria.

> It has always been inconsistent.

> It worked for a while but then totally stopped.

“The bioreactor works great, but …”

> Recommissioning after shutdowns takes months.

> Our chemistry is going to change, and no one can tell us what that might mean for future treatment.

> Why are there high total metals coming out occasionally?

I am an advocate for biogeochemical water treatment in the mining sector, and yet I am also the first to point out that there is case after case of “troublesome” bioreactors that are unpredictable and inconsistent, failing to meet promised expectations. Bioreactors can be used to treat a range of things for mine-impacted water. I have worked with many successful active and semi-passive bioreactors that treat ammonia, nitrate, nitrite, thiocyanate, cyanide, selenium, manganese, copper, nickel, zinc, and a whole range of other metals. But I have also seen utter failures of bioreactor implementation for even the simplest things such as ammonia and nitrate.

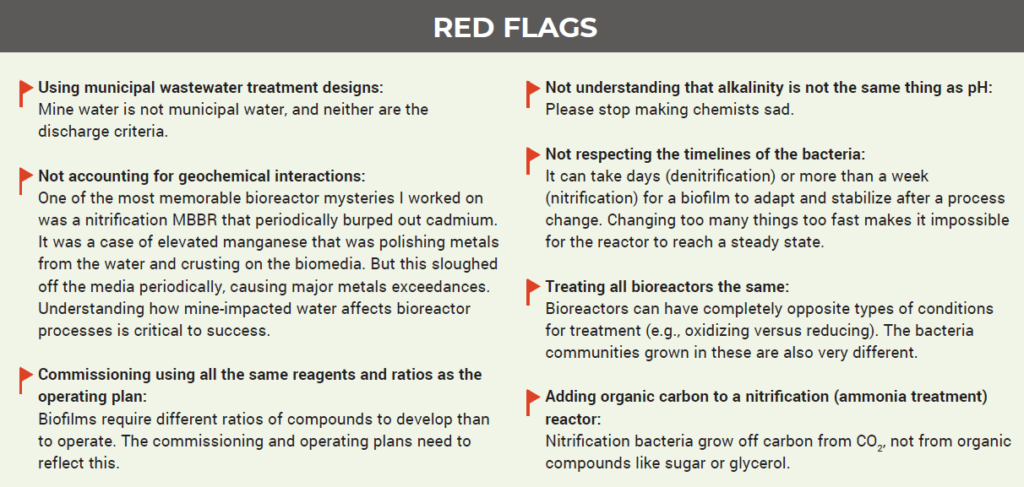

Here, I correct what I consider the top seven myths of bioreactors and outline common red flags of “broken” bioreactors to help the mining community and take a step towards putting my “fix the broken bioreactor” services out of business.

MYTH 1:

Bioreactors do not work at cold temperatures.

Reality 1: Bioreactors can work at any temperature when water is liquid. Treatment of some compounds is directly temperature dependent, and others are not. There is an ammonia nitrification moving bed bioreactor (MBBR) operating in northern Saskatchewan for over a decade at temperatures of 2°C to 4°C.

MYTH 2:

Bioreactors take months to commission.

Reality 2: You should typically expect to see treatment in a denitrification reactor in 2 to 3 days, or a nitrification reactor in 7 to 10 days. Selenium treatment or metals treatment through sulphide co-precipitation take slightly longer to establish at up to 2 weeks. Full treatment of any TRL 8 or 9 type bioreactor application should be achieved in under a month for consistent feed water.

MYTH 3:

You can use municipal water treatment software to design a bioreactor.

Reality 3: With mine water, you regulate the carbon and phosphorus as reagents to control the treatment of nitrogen, sulphate, selenium, etc. This looks like a municipal MBBR on a diagram. Do not let appearances fool you though; it is very different biogeochemical design and operation than municipal wastewater where all nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon are present in the water and require treatment.

MYTH 4:

Bioreactors create lots of total suspended solids (TSS).

Reality 4: Ammonia (nitrification) bioreactors produce almost no TSS. Nitrate (denitrification) and sulphide producing bioreactors should produce very small amounts of TSS. Most should be low enough TSS to directly discharge. High TSS concentrations occur when the carbon and/or phosphorus are being overdosed, such as using ratios common in municipal wastewater treatment.

MYTH 5:

Bioreactors are the “best achievable technology” (BAT) for blah.

Reality 5: There are dozens of types of bioreactors. Additionally, there are many ways to operate each type. While there are types of bioreactors that are the BAT for the treatment of a specific constituent (e.g., an aerobic moving bed bioreactor for ammonia), this cannot be applied as a blanket statement. Specifying the type of bioreactor is critical to determining its applicability and technology readiness.

MYTH 6:

Bioreactors are a ‘black box’ and the reactions inside are unknown.

Reality 6: The reactions inside bioreactors are well-understood and documented in decades of scientific research. Unfortunately, this does not mean they are always used.

MYTH 7:

You need to use an “inoculum” to start the bioreactor.

Reality 7: If your water has been exposed to wind, rain, or rock, then bacteria are there. Unless using inoculum from a nearly identical bioreactor, adding in bacteria produces fast unsustainable results and prolongs the overall commissioning. Many genomic studies over the past decade have shown that added bacteria typically last a few days in the bioreactor but delay the establishment of consistent operations of the bioreactor by weeks or months.

Dr. Monique Simair is a globally recognized leader in passive and semi-passive water treatment for the mining sector, including bioreactors, constructed wetlands, in situ treatment, and contaminant source control methods. She is the founder and CEO of Maven Water & Environment (www.mavenwe.com) and can be contacted at monique@mavenwe.com.

Comments