Biggest & Best Yet?

An old saw in the mining trade goes that “tomorrow’s mine might be right next door to yesterday’s.”

If that holds, a Barrenlands gold deposit with historic roots and keen owners could become the next and largest mining operation in Canada’s North.

Toronto-based Seabridge Gold Inc. (TSX:SEA) has been steadily proving up the FAT deposit (the acronym for the deposit’s Feldsic-Ash-Tuff geology), adding positive results to almost 30 years and 150,000 metres of drilling done by previous explorers Noranda, Getty, Total and Placer Dome since 1976.

The find is in Seabridge’s 53 km2 block of the Matthews Lake Greenstone Belt, host to the expired Tundra (1964-68) and Salmita (1982-87) mines at Courageous Lake 240 km northeast of Yellowknife.

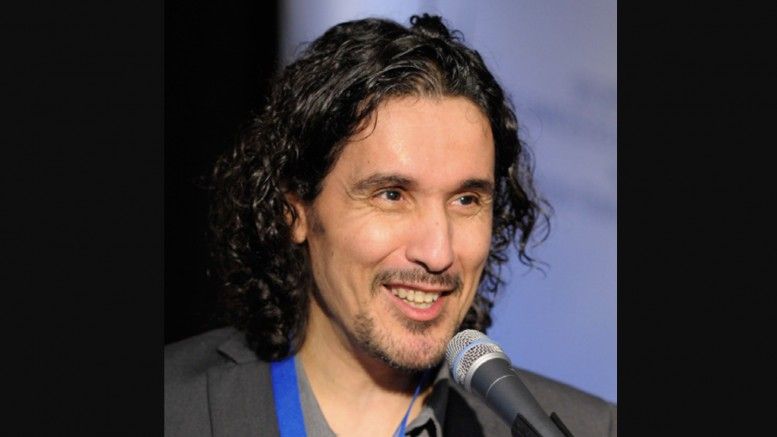

“When we bought it in 2002, known historic resources were 5.7 million ounces, almost all inferred. We’ve extended resources by 80 per cent,” said Rudi Fronk, Seabridge president and CEO.

And he’s hopeful that final results of the 2010 drill program will add even more to the inferred gold resource, now pegged at 6 million ounces plus 4.2 million measured and indicated from an average grade of over 2.0 grams per tonne.

While the old Tundra and Salmita properties were underground, Fronk envisions a massive 25,000 tonne-per-day open pit operation, as deep as 600 metres. There is potential for future underground development to harvest even higher yields logged as deep as 1,000 metres.

Such an operation would eclipse even the huge diamond pits further down the existing Tibbitt to Contwoyto ice road that would supply a future operation.

“The diamond mines have been helpful to us,” says Fronk of the neighbouring Diavik and Ekati developments. “They’ve been able to demonstrate you can operate large tonnage, big open pit, year round in that environment.”

Long vision on gold paying off

“We started Seabridge in 1999 with a view that, at that time, gold (at well below $300/oz) represented a good time to get back into that business,” he said. Good timing indeed: their initial 15 cent stock now trades in the $30 range (late November 2010).

Fronk, with degrees from Columbia University in mining engineering and mineral economics, has 20 years experience with publicly traded gold companies. The company’s business plan wanted large existing resources with low holding costs that need much higher gold prices to yield returns.

The NWT prospect, and the much, much larger KSM copper/gold deposit in northwest British Columbia, fit that mould. In fact, the KMS’s 1.6 billion tonnes of proven and probable reserves containing over 30 million ounces of gold plus 7 billion pounds of copper make it the largest deposit ever found in Canada, and has been the primary focus for Seabridge over the past four years.

But the $20 million invested in 2010 at Courageous Lake made it one of the biggest programs in the NWT (one-fifth of total exploration spending) and it will likely be matched again in 2011. Fronk anticipates an updated preliminary assessment study by the first quarter in 2011 to be followed by a preliminary feasibility study in early 2012.

With a lean, full-time staff of only 11, Seabridge relies heavily on service contractors, many of them northern based: EBA Engineering, Rescan Environmental Services, Matrix Logistics, Trinity Helicopters, Arctic Sunwest, Air Tindi and Summit Air. Southern-based support included Hytech Drilling Ltd. and Wardrop Engineering and Moose Mining Technical Services.

Seabridge does not, however, plan on being the developer. Its business model directs that each property will need a joint venture partner, or a takeover by a major “with deep pockets and strong technical capabilities and a good track record,” said Fronk.

A 2008 assessment projected an 11.6 year life, producing 500,000 ounces annually at an average cash cost of $435 (US). Further development at FAT includes particular attention to building relations with as many as five different First Nations in the region.

Transport, Energy Challenges

The 2008 projection pegs start-up costs at $848 million (US) and, like any northern mine that’s off-grid and off-road, energy and transport systems really bulge the budget.

The site already has the advantage of a short airstrip and surface road network from its ancestors and it already uses the seasonal ice road. But that road provides only a narrow, eight-week supply window, and any development needs costly, year-long inventories.

“If you could have a year-round road you’d be reducing your capital costs and your operating cost dramatically,” Fronk said, but was not able to put a dollar amount to what it could save.

Likewise for energy: to offset diesel for its planned 50 megawatt demand, Seabridge is looking at both wind and the Snare River system to the south, already tapped as the main source of hydro for Yellowknife.

“If you could bring in a hydro source, compared to the amount invested in a diesel plant, it would have huge impact on the economics, more so than a year-round road would have,” he said.

Seabridge’s good fortune does not include finding diamonds on its claim. “They’re in the granites where we are not looking,” says Fronk. But he still speculates on how luck played a role in the FAT’s original discovery when Noranda originally went into the area looking for base metals in the 1970s.

“How many other examples are there of going out to get one thing, and finding another? In this business, you gotta be lucky, you really do.”

Comments