Better Outcomes Through Sustainable Landfill Design

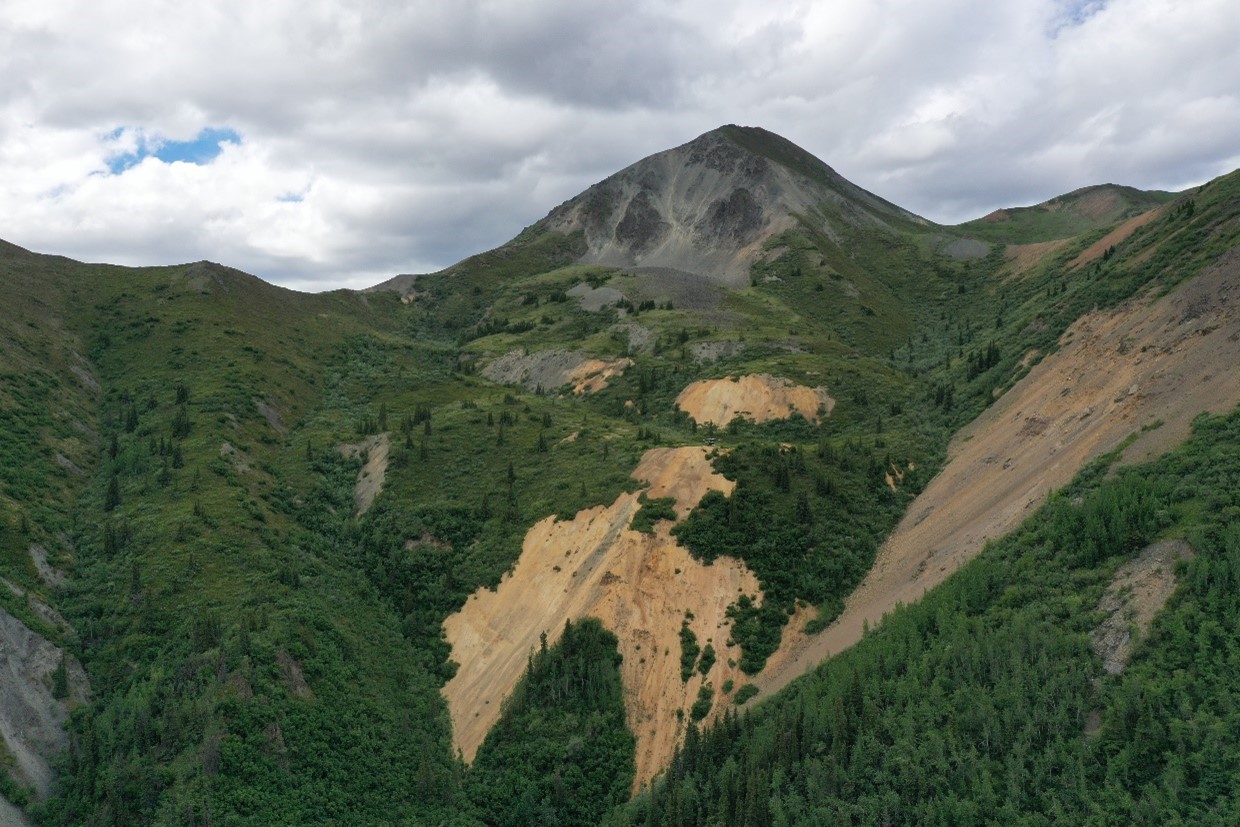

Even from a plane at cruising altitude, they stand out. Piles of rock in straight rows, with wide, level tops and straight sides, often with little or no vegetation, protrude from the surrounding landscape – clearly, a mine waste dump. Possibly from a long-closed mine, such waste facilities form a lasting legacy of mining in many parts of the world.

However, the plane may also be flying over other mine waste dumps, which are much less likely to be noticed. Designed with size and slope characteristics that match those of the surrounding topography, these “geomorphic” landforms blend right in.

Compared to their straight-line “structural” counterparts, geomorphic landforms look like natural hills. They generally have several small peaks instead of a level top so water has little chance to collect, and sides that are steeper near the top, less towards the bottom. The best landform designs are often those based on studies of nearby topography, matching the curves and slopes found in nature.

Structural landforms are almost certain to fail over time. They erode, possibly causing sedimentation and ARD to flow into watercourses. Many members of the public are starting to question whether the companies that earned revenue from the mine will be in position to continue to manage these sites, and prevent environmental damage long term. Or, will taxpayers need to put resources towards maintenance and repair in the case of failure at a mine waste facility?

Financial sources are increasingly conscious of the environmental and social effects of the companies in which they invest. A company that is unable to meet their criteria may face a higher cost of capital and fewer sources to choose from.

Just as is the case when a consumer quietly decides to boycott a particular store or manufacturer, financial sources may just decide to take their money elsewhere if they feel that a company’s actions may not be in line with the social and environmental expectations of their shareholders.

An increasing focus on landforms

Many of the issues that have dogged the resource extraction sector have to do with closure, whether it is the oil sands in Alberta or downstream risks from sub-aqueous tailings storage facilities from hard-rock mining. Mine waste dumps are starting to attract greater attention.

Some of this has to do with the ease with which images and text can be spread worldwide – any non-governmental organization can take video or still images of a mine waste dump and, with a mouse click, send those images globally.

Mine landforms are big, often towering over the surrounding landscape and vegetation, and are easy to show in a photograph. At least to a non-technical eye, the straight lines and setbacks of the structural landforms are unappealing partly because they are so unlike what is found in nature. Add to this the inherent long-term maintenance required of structural landforms and their likelihood of accelerated erosion, and the result may well be a well-positioned image of a company’s mine waste facility in an environmental advocacy group’s mailing or YouTube video.

With the rise of concern about the future of Planet Earth, members of the public are asking more questions about what legacy the current generation is leaving for future generations, who may have had nothing to do with a nearby mine but must live with its long-term consequences.

Reputational risk goes well beyond the implications for a mining company’s stock price and its ability to raise financing. Regulators and governments are paying greater attention to the needs of people who are affected by the landforms left behind by mining companies. This includes the implications for communities that depend on tourism, including back-country hiking, skiing and hunting.

We also see a wider definition of “productive” when it comes to mine site reclamation. If the land can be moved without delay onward to its next use such as natural habitat, forestry or tourism, this can promote good relations between the mining company and governments at all levels.

Mining companies that have a reputation for good environmental and social stewardship are more likely to get approval for their plans for a new mine or an expansion of an existing mine. If a project can get green-lighted quickly rather than being dragged through months or years of review and community consultation, it can start earning revenue and produce a return on equity sooner.

Supporting walk-away closure with landforms that function like natural systems

Part of the answer to the mining sector’s need for a positive image comes in the design of the landforms it leaves behind.

Structural landforms may be popular with mine planners because they are easy to design, build and may attract minor cost savings. However, as the science behind geomorphic design becomes better established, and as its principles see more application among miners, this cost difference is changing.

Although structural landforms meet current regulations in many jurisdictions, the regulatory scene is also shifting in favor of geomorphic design.

Our conversations with regulators indicate that they are well aware of the benefits of geomorphic landforms for delivering sustainable disposal of mine waste. Many regulators say that partly because changes in the regulations can be a very slow process, they are willing to work with mining companies that are interested in providing a better outcome through more sustainable practice, including the use of geomorphic design.

As well as better understanding of how mimicking Mother Nature’s designs in landforms can improve mine waste sustainability, there is also research being done on the design of artificial watercourses with sinuosity that is like that of natural streams and rivers. Like the curving lines of geomorphic landscapes, the bends in geomorphic streams help slow the flow of water and reduce erosion.

Research in universities and elsewhere also focuses on sustainable vegetation – plants that grow quickly to anchor soil in place, but with a focus on choosing plants that will not all mature at the same time, so that more natural vegetation progression is possible.

While the idea of producing landforms, watercourses and vegetation that are like those found in nature close to the mine site may carry some additional cost, the benefits are becoming clearer. Companies that build their expertise in this area, and that build their landforms right from the start in a more natural way, will find their decisions to be a source of competitive advantage.

This article is based on a workshop that the author will be facilitating at the Mine Closure 2011 conference (www.mineclosure2011.com), to be held 18-21 September in Lake Louise, Alberta, Canada.

Anil Beersing is a Principal and Senior Water Resources Engineer in the Calgary, AB office of Golder Associates Ltd.; tel 1+403.299.5600; abeersing@golder.com.

Comments