Almost Ready

As a child growing up in the Cape Breton coal-mining community of Glace Bay, John Morgan attended Warden United Church and, to this day, he remembers the stained glass windows and the coal miners depicted alongside the usual religious imagery.

He lived in a neighbourhood known as Number Two, a reference to the closest pit head, and four other nearby residential areas were so named as well. “A lot of our culture is tied to the mining industry,” says Morgan, a 46-year-old lawyer and mayor of Cape Breton Regional Municipality. “It’s part of who we are.” Or, perhaps that should be: who we were.

DEVCO – the federally owned Cape Breton Development Corporation-closed the region’s last underground mine in 2001, nearly four centuries after French colonists from the lonely military outpost of Louisbourg first extracted hard, black fuel from deposits at or near the surface. The death of the industry has been a source of some considerable duress–both emotional and economic-for local residents. “The company gave us the announcement on May 16, 2001,” recalls Bob Burchell, Canadian representative for the United Mine Workers of America. “It was my birthday. It was a sad day for Cape Breton.”

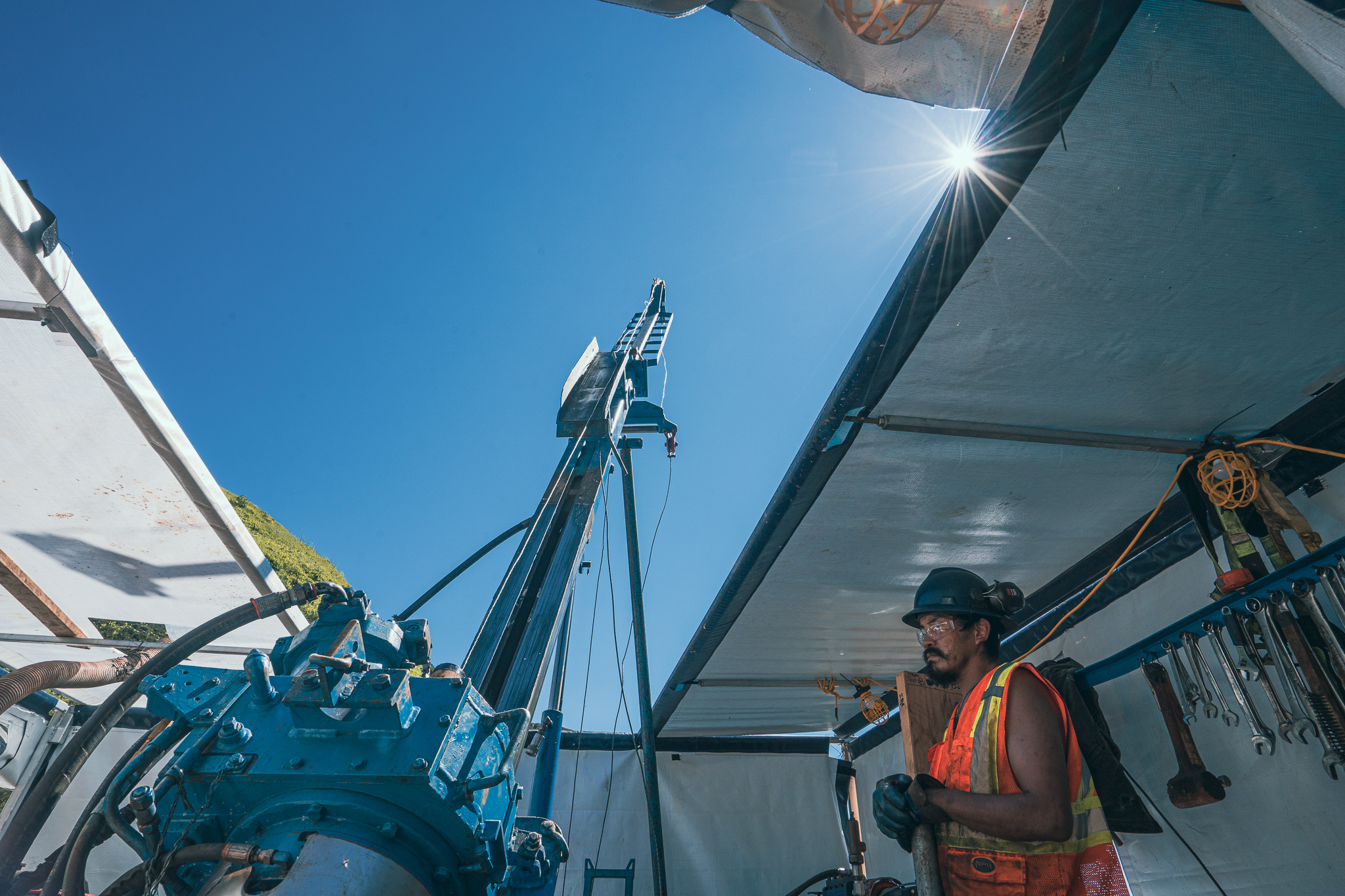

But these days, Cape Bretoners are keeping fingers crossed and hopes high that a revival is just around the corner. Since 2006, the Swiss-based, global mining giant Xstrata and its local partner, Erdene Resource Development Corp. of Halifax, have put some $30 million into the development of the Donkin coal resource block, which is the region’s last, large untouched deposit. The two companies are currently at work on a pre-feasibility study and have said that their objective is to build an underground mine capable of producing 2.75 million tonnes per year of export-grade coking coal. It would initially create 200 jobs, but with spin-offs could generate employment for up to 1,000 people.

Officials with both Xstrata and Erdene have been tight-lipped in recent months about their progress. Indeed, the last public statements were issued in February, 2010 after a packed public meeting at a firehall in the village of Donkin, from which the project takes its name. “Xstrata Coal remains committed to the Donkin Coal Project and we will continue to liaise with key stakeholders….,” the company’s chief development officer, Jeff Gerard, said at the time. “This is a significant project for the people of Nova Scotia and the people of Cape Breton.”

The entire Donkin block is believed to occupy an area of 110 square kilometres and to contain 227 million metric tonnes of indicated coal and an additional 254 million metric tonnes of inferred coal. Xstrata and Erdene plan to exploit the Harbour seam first, which is believed to hold an indicated resource of 101 million tonnes and an inferred resource of 115 million tonnes. According to documents released by Erdene, the resources have been assessed as “high volume A bituminous, high-sulphur, medium-ash coal…”

“I believe the Donkin deposit is unrivalled globally in terms of quality, quantity and strategic location,” says Peter Akerley, president and CEO of Erdene, which holds a 25 per cent interest. “Donkin is an exceptional deposit. Its high energy and very good coking properties, along with its thickness, all add to its value.”

Given the size and quality of the deposit, the two companies are not the first to attempt to develop them. DEVCO devoted a decade–between 1977 and 1987–and spent an estimated $100 million exploring and evaluating the resource. Like most of the Cape Breton coal seams, the Donkin deposit begins beneath the mainland but extends offshore. DEVCO drove two adjacent tunnels into the Harbour seam. Each was about 7.6 metres in diameter and some 3.5 kilometres in length. Unfortunately, world demand for coal sagged before DEVCO was able to begin mining. Operations were suspended, pumps were shut off, the tunnels were sealed and groundwater slowly inundated them.

That’s where things stood until December 2004. World markets had changed drastically since the late 1980s. Demand for both thermal and metallurgical coal was on the rise-thanks in no small part to the new manufacturing might of China and other emerging economies-and the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources put out a request for proposals to lease and develop the Donkin block.

In December 2005, the Nova Scotia government announced that the successful bidder was the Donkin Coal Alliance, a consortium of four companies that has since been whittled down to Xstrata and Erdene through a number of corporate mergers and acquisitions. By June 2006, the Nova Scotia Cabinet had approved the application and work proposal submitted by the alliance and had granted an exploration license.

The first order of business was to de-water and rehabilitate the DEVCO tunnels-a costly and time-consuming process. While that was being done, Xstrata engineers and geologists conducted a comprehensive review of data, that had been compiled by DEVCO and was based on some 20 holes drilled from the surface into the subsea deposit. The company also took a bulk sample from the face of the Harbour seam and conducted horizontal and directional drilling at the face.

Initial mine models, including an annual production target of four million tonnes, were based on the assumption that Nova Scotia Power would be the major customer. In late 2009, however, the utility informed the company that Donkin coal contains too much mercury and sulphur to meet current environmental requirements and could not be burned in its thermal generating plants. That forced the partners to change direction. They went back to the drawing board and in February 2010 announced a new plan to develop a mine based solely on coking coal for export markets. Anticipated yearly production was trimmed back to 2.75 million tonnes.

Akerley notes that Donkin’s location on the eastern tip of Cape Breton provides a significant competitive advantage over mines in Wyoming and the Appalachians, which are already sending coal hundreds of miles by rail to the East Coast for shipment to overseas customers. Donkin coal can be loaded onto barges at the mine site and transferred to ocean-going vessels anchored a few kilometres offshore.

“It’s an ideal situation that I believe exists nowhere else on earth,” he says. “Nowhere else do you get this size of deposit, this quality, the infrastructure and this depth of water all in combination.”

The barge-to-ship plan will require a Federal Environmental Assessment to ensure that it poses no threat to offshore fisheries, among other things. It has also put frowns on the faces of port authorities in nearby Sydney. They were hoping that Xstrata might build a railway and ship the coal some 35 kilometres to their deepwater harbour, where it could be loaded onto vessels.

Nevertheless, the project has been welcome news in a depressed region where the official unemployment rate fluctuates between 13 and 15 per cent, where the labor participation rate is well below 50 per cent and where dozens of displaced miners have had to head west to find work in the Alberta oilsands or the diamond mines of the Northwest Territories.

“The opening of this mine would give us hope,” says Mayor Morgan. “These are typically good paying jobs in a community that is struggling, and has been for a long time.”

¿

Comments