Risk management considerations when expanding abroad

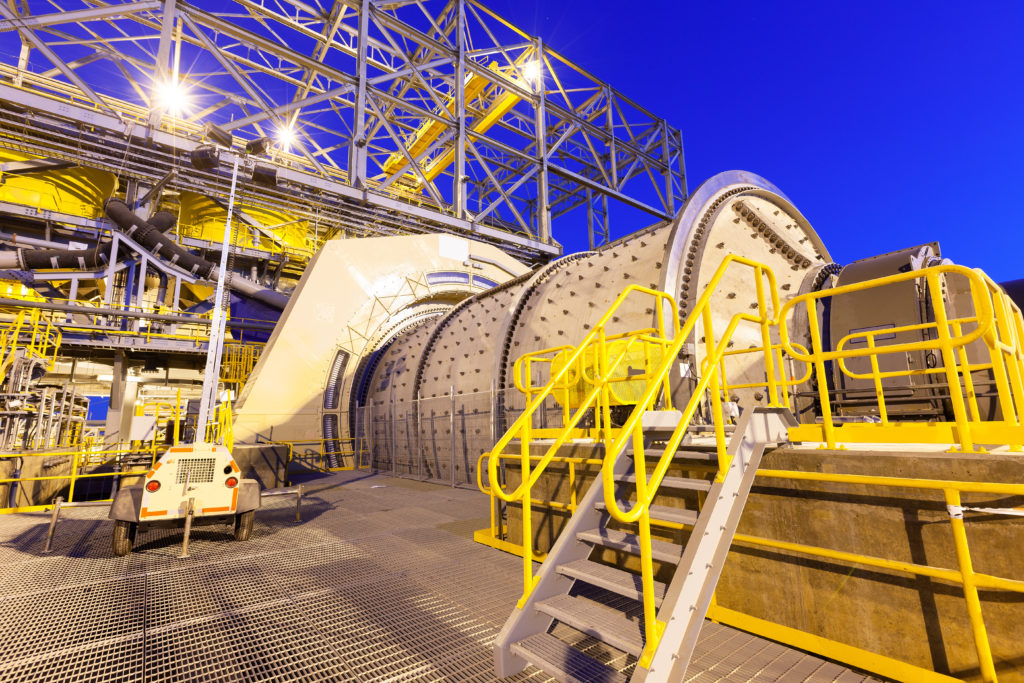

With the global distribution of minerals and the associated opportunities, miners need to go to where these resources and opportunities are available. That frequently involves entering joint ventures, licences, and other agreements in new jurisdictions. What steps can companies take to consider managing risk when evaluating and proceeding with international opportunities? In this article, we set out some considerations that miners ought to keep in mind to protect their business.

Investment structuring

Investment structuring involves setting up one’s business arrangements in another country (the host state) to leverage investment protections provided in bilateral or multilateral treaties. While these treaties refer to protecting “investors,” what they are actually protecting, depending on the nuances of any particular treaty, can include a public or private company, or a subsidiary of such a company, an investment fund, an individual entrepreneur, a shareholder or any entity that meets the particular definition of “investor.”

The protections offered to the “investor,” again depending on the specific wording of a treaty, usually include the following:

- National treatment: an obligation to treat the foreign investor no worse than a local investor in like circumstances.

- Most favoured nation treatment: a requirement to treat the foreign investor no worse than foreign investors from another state getting preferential treatment from the host state in like circumstances.

- An obligation to provide a base level or minimum standard of treatment.

- A requirement to provide full protection and security against acts of the government and private parties.

- A prohibition against expropriation without reasonable compensation.

In many cases, these treaties can also address tax protections to ensure tax stability for the investors entering the country, considering mining often involves long-term investments.

For those looking to enter a new venture in another country, the protections offered by these treaties, of which there are thousands in force around the world, provide tools to manage political and regulatory risk. Beyond substantive protections, investment treaties also offer procedural protections that can be appealing, such as the ability to bring a claim directly against the host state through international arbitration if a substantive protection is violated. This process removes the claim from that host country’s local judicial system, placing it under international law to be addressed by a tribunal experienced in handling such disputes. Failing to address structuring to take advantage of available treaties at the outset may prohibit a miner from later taking advantage of a treaty.

Contractual protections

In addition to the protections offered by treaties, miners and host states may establish, through private contracts, stabilization clauses that address potential changes in the host state’s law throughout the project’s duration.

The three primary types of stabilization clauses are

- “freezing clauses,” which exclude the investment from the application of new laws, whether pertaining to any new legislation or limited to specific regulatory areas;

- “equilibrium clauses,” which aim to compensate for losses incurred because of the changes in host state law; and

- “hybrid clauses,” which combine elements of both types. Ultimately, these clauses establish legally protectable expectations for investors that may entitle them to seek compensation.

If well designed, these clauses can facilitate large-scale and long-term project investments. However, it is important to clarify that the existence of these clauses does not prevent the host state from enacting new legislation; instead, they aim to ensure that any changes in the legal framework are applied in a way that is fair, rational and non-discriminatory toward specific investors. To achieve this, the contractual framework must be aligned with the host’s legal landscape, considering potential changes in areas such as environmental standards, social licensing, or other relevant regulations. This approach helps protect the investor’s legitimate expectations, reducing the risks of adverse impacts or discriminatory treatment. Additionally, special attention must be paid to the host state’s risk profile, particularly regarding the political risks of expropriation or nationalization, political instability, social and environmental, international sanctions, corruption, or the existence of an inadequate judicial system or weak rule of law. To mitigate these risks, miners may seek political risk insurance from either private companies or public providers, such as export credit agencies or multilateral credit institutions. Furthermore, to address contingencies such as inflation, price fluctuations, or supply chain disruptions, projects may be structured through a streaming agreement to pre-allocate these risks.

The existence of stabilization clauses does not prevent the host state

from enacting new legislation.

Mining activity is exposed to several factors that escape investor control and can substantially alter mining operations. Therefore, miners should consider, where beneficial under governing laws, incorporating strong and broad force majeure clauses as an effective risk allocation tool. These provisions can serve as an excuse for the party’s non-performance of its contractual obligations because of reasons outside its reasonable control. Hardship provisions may also be helpful to open the possibility of a renegotiation of the terms of the agreement if the contractual equilibrium is altered in such a way that the performance of the contract becomes ruinous for one of the parties. Where contracts address several phases of a mining development such as exploration, exploitation, and closure of the mine, it is also important that the contract address the transition to each one of the phases, considering all the requirements that these transitions may involve (i.e., governmental approvals or permitting). Other provisions that are relevant and required to be addressed by the investors involve liability clauses, any insurance requirements, and termination for convenience or early termination clauses.

In summary, it is crucial for miners to consider adapting the contractual and corporate structure of the project to the local framework and the risk profile of the host state, as well as considering the broader global context.

Ricardo Balestra is a partner in Dentons, based in Buenos Aires. He specializes in the areas of corporate law and energy with more than 15 years of experience in international transactions with a special focus on Latin America.

María del Mar Heredia is a partner at Dentons, based in Quito. She is the legal director of the contracts, M&A, energy, mining, and oil areas at the firm.

Rachel Howie is a partner at Dentons, based in Calgary. She is the co-leader of the litigation and dispute resolution group in Canada, and national alternative dispute resolution and arbitration group.

Sergio Kosik is a senior associate at Dentons, based in Buenos Aires. He oversees diverse client matters, leading a team of junior and semi-senior lawyers focused on addressing the day-to-day legal intricacies faced by multinational companies operating in Argentina.

Michael R. Rattagan is a founding partner of Dentons’ Argentinean office. He co-leads the M&A and natural resources and energy groups in Buenos Aires and has 30 years of experience in advising international companies on commercial, corporate and contractual matters, acquisitions, oil and gas, mining and energy.

Comments