Norway plans to open its water to deep sea mining

The Norwegian Parliament is considering opening its territorial waters for commercial seabed mining. The vote on whether exploration and mineral extraction will be allowed or not will take place in Jan. 2024. If approved by parliament, Norway could become the first nation to undertake deep sea mining on a commercial scale.

The proposed plan follows similar principles to opening offshore areas to oil and gas exploration. From the overall area, smaller zones, or blocks, would be offered to companies to explore and extract.

Walter Sognnes, CEO of Norway’s Loke Minerals, estimates that if the vote is passed, licenses could be issued within six months, and exploration could begin in the spring of 2024 or 2025. Loke Minerals plans to mine polymetallic nodules in the Clarion Clipperton Zone, and possibly from the Norwegian continental shelf if exploration is given the green light. Sognnes estimates there are four or five Norwegian exploration companies which are hoping to participate in the industry.

Norway is one of the world’s wealthiest nations because of its oil and gas deposits but wants to turn from using fossil fuels to greener energy and technological alternatives. The Norwegian government believes that deep sea mining could help Europe reduce its dependence on China for the supply of critical minerals needed to build electric vehicle batteries, wind turbines, and solar panels.

Deep sea mining supporters believe that harvesting minerals from the deep sea instead of land is cheaper and has less of an environmental impact, and that it is needed to meet the increasing demand of mineral growth. The demand for copper and rare earth metals is predicted to grow by 40% by 2030, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). The agency also expects that demand for nickel, cobalt, and lithium will increase by 60%, 70%, and 90%, respectively.

“We need minerals to succeed with the green transition,” said Petroleum and Energy Minister, Terje Aasland, adding that mining the seabed could be an “important source of minerals”. Mineral deposits on the Norwegian continental shelf include polymetallic nodules, manganese crusts, and massive sulphide deposits located by thermal vents.

“Of the metals found on the seabed in the study area, magnesium, niobium, cobalt, and rare earth minerals are found on the European Commission’s list of critical minerals,” said a statement by the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD).

It is estimated that resources in the continental shelf include 38 million tonnes of copper, nearly twice the amount mined each year. Manganese crusts contain approximately 24 million tonnes of magnesium, 3.1 million tonnes of cobalt, and 1.7 million tonnes of cerium, a rare earth element used in alloys. The crusts may also contain neodymium, yttrium and dysprosium, other rare earth elements. In addition, it is estimated that polymetallic sulphides contain 45 million tonnes of zinc. However, according to Sognnes, the sulphides are difficult to mine and may not be commercially viable.

The minerals and metals are estimated to be worth US$100 billion and create 20,000 new jobs according to an independent study by the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

“If proven to be profitable and extraction can be done sustainably, seabed mineral activities can contribute to value creation and employment in Norway while ensuring the supply of crucial metals for the global energy transition,” said Aasland.

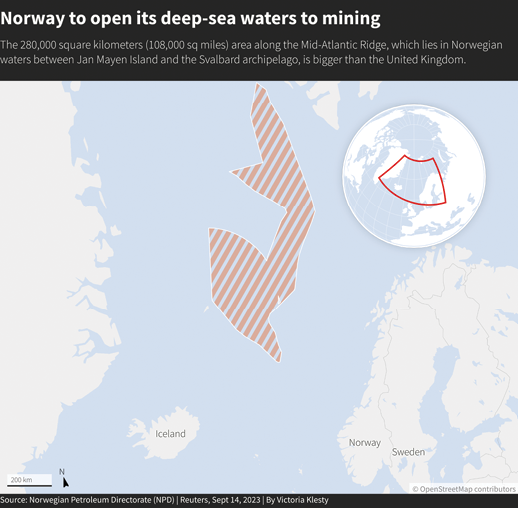

The areas which may be opened are in the Greenland Sea, Norwegian Sea, and Barents Sea. The area is approximately 280,000 km2, about the size of Ecuador. However, very little of the shelf has been mapped.

According to State Secretary, Astrid Bergmål, “Norway has a long tradition for prudent, responsible, and sustainable resource management. Due to the lack of knowledge in the deep sea, we will apply a precautionary approach through a stepwise development where the licensee will be tasked with collecting data on both the resource potential, as well as biodiversity in the area and possible environmental impacts. Extraction will only be approved if a developer can document that the proposed plan is prudent and sustainable.”

Since the government revealed their plan earlier this year, they are facing opposition from both within and outside the government. Norway’s minority government is facing opposition from its key ally in parliament, the Socialist Left (SV) party.

Lars Haltbrekken, SV’s spokesman on energy and environment, stated that a moratorium of at least ten years is necessary to better understand the environmental consequences of deep sea mining before proceeding with seabed mineral extraction.

Scientists have found unique species living around active hydrothermal vents, such as corals, tube worms, and microorganisms. Little is known about how these ecosystems work. A government-commissioned impact study said the impact would be limited to actual area where the extraction occurred, and that the impact on fisheries would be minimal.

CREDIT: GREENPEACE

Haldis Tjeldflaat Helle, Greenpeace’s deep mining campaigner in Norway states, “In the area, we found a great variety of life forms including small, specialized microorganisms which provide the basis for corals, which again is spawning grounds for fish, octopuses, and other mobile marine species. These are key food sources for whales, seals, and marine birds. Deep sea mining directly threatens the species on the seabed, but also has the potential to heavily impact the food sources of many organisms who live across the water column. It will also further increase the sound pollution of the ocean, which has grave impacts on vulnerable species such as whales who rely on sound and echolocation to communicate, navigate, and hunt.”

“We still know too little about the ecosystems in the deep sea, how they interact with other ecosystems, and what kind of technology which will be utilized to mine the deep sea,” says Helle.

According to Helle, Norway’s plans have met resistance from marine and environmental science institutions in Norway, including the Norwegian Environmental Agency, the Institute for Marine Research, the University of Bergen, the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and the Norwegian Institute for Polar Research. In addition, Norwegian fishing organizations are concerned about the effect on fisheries.

Susanna Fuller, of Oceans North, states, “I am surprised that Norway has done this. They are thinking we must get off oil, what else do we have that can keep us prosperous. Norway is one of the lead countries in the Ocean panel, and to be one of the first developed countries opening the European Economic Zone (EEZ) is a little bit surprising.”

Denmark said Norway’s environmental study for the area opening was not good enough, while Iceland questioned Norway’s exclusive exploration rights for seabed minerals near the Arctic Svalbard archipelago.

Currently, 22 governments are calling for a moratorium to gather more information on the industry’s potential environmental impact. Canada has banned deep sea mining in both its territorial and international waters.

Nearly 800 scientists, 36 large companies including BMW, Google, Samsung, Volkswagen, Volvo, and Philips, 37 financial institutions, the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, fishing groups, Indigenous Peoples, youth, and local communities have urged the International Seabed Authority (ISA) to halt the industry.

Scientists warn that it would result in an irreversible loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services and species extinctions. Companies including Samsung and BMW have also pledged to avoid using minerals mined from the deep sea.

The ISA which regulates deep international waters recently held meetings in Jamaica with its 168 member states to continue discussions on drafting a deep sea mining code. The ISA’s July session did not allow commercial-scale deep sea mining to begin.

A Canadian company, The Metals Company (TMC), triggered a two-year legal loophole when it applied for a mining license in 2021. The loophole allows companies to apply for provisional mining licenses even if a mining code has not been drafted. Member states have agreed to draft and adopt a mining code by 2025.

The ISA has issued more than 30 exploration licenses. China holds five, and 22 countries have been issued licenses. Much of the exploration is focused in an area known as the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone, which spans 4.5 million km2 between Hawaii and Mexico at depths from 4,000 to 6,000 metres. No provisional mining licenses have been issued to date.

One of the industry’s staunchest opponents is the Netherlands based Deep Sea Conservation Coalition (DSCC). Duncan Currie, the DSCC’s legal advisor, commented that “Adoption of the mining code would inevitably lead to irrevocable mining contracts which would be in place for many decades. The proposed mining code would effectively allow deep sea miners to write their own rules, while independent and transparent scientific evidence is missing. There is not even a scientific committee in place.”

Loke Minerals, a Norwegian deep sea exploration company, hopes to harvest the polymetallic nodules from the seabed floor in the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ), and possibly in Norwegian waters, in the future. They purchased Lockheed Martin’s deep sea mining division in March 2023, and acquired its two U.K. licenses in the CCZ. Approximately 31 licenses have been granted to 17 countries.

Norway is one of the only countries in the world to have its own legislation regulating the industry in its territorial waters. Its Seabed Minerals Act was introduced in 2019.

The Norway Seabed Minerals Act provides regulations on “exploration for and extraction of mineral deposits on the Continental Shelf in accordance with societal objectives, in such a manner that safeguards considerations such as value creation, environment, safety, other business activity, as well as other interests. This Act does not apply to scientific research on seabed mineral deposits.”

The Act applies to mineral deposits in Norway’s internal waters, Norway’s territorial waters and on the Norwegian Continental Shelf. Territorial waters refer to the sea area from the baselines out to twelve nautical miles. Internal waters are the sea areas within the baselines.

A license approved by the government will be required before companies begin any scientific research, exploration, or mineral extractions. Before any new areas are opened, the ministry will conduct an impact assessment and give stakeholders three months to submit statements. Impact assessments indicate the effects a potential opening could have for the environment, business, economic and social factors.

Written applications for survey licences designate the geographical area, which surveys will be conducted, which mineral deposits will be examined, and timeline. Survey licences may be granted for up to five years.

Extraction licences give the licensee the exclusive right to conduct surveys and extraction of all mineral deposits in the area covered by the licence. An extraction licence may be granted for up to ten years and extended up to 20 years.

Catherine Hercus is a freelance mining writer.

Comments