Deep sea mining faces a sea of opposition

The Metals Company (TMC), a local British Columbia company, plans to mine polymetallic nodules from the seabed floor. Unfortunately, their plans for deep sea mining are facing a sea of opposition. Not only is the company facing local and worldwide opposition from governments, Indigenous, and ecological groups, but they are also battling financial issues.

Their three exploration contracts are located off the island of Nauru, the Kingdom of Tonga, and the Republic of Kiribati in the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ) between Hawaii and Mexico. Approximately 30 companies have been issued exploration contracts to mine in this area. This zone in the Pacific Ocean contains the largest known deposit of battery-grade metals.

What makes the area so attractive according to Dr. John Wiltshire, the director emeritus of the Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory, is that “nodules need a flat zone, low sediment, good plankton growth, and the area to remain stable for the best concentration. Nodules are found on 15% of the bottom zone worldwide.”

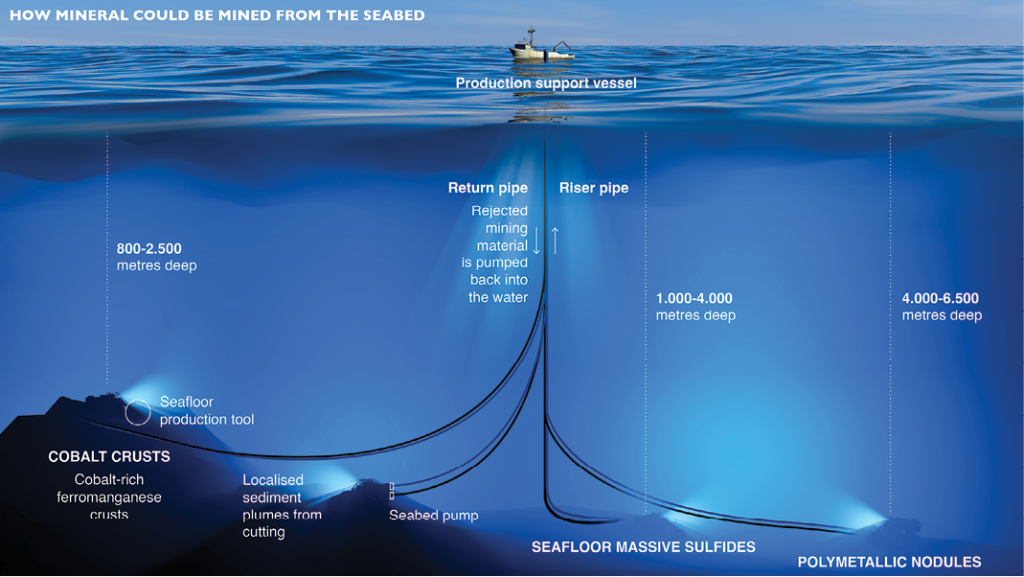

Polymetallic nodules look like potatoes and contain minerals including cobalt, copper, manganese, and nickel which are used in electric vehicle (EV) batteries and other clean energy technologies. Unlike cobalt crusts or seafloor massive sulphides, which require cutting hard rock, nodules are harvested with a vacuum- like collector which lifts them up from the abyssal seafloor. From there, they travel up a riser system to the production vessel on the surface. On the vessel, the nodules are dewatered, and they are then transferred to an onshore processing facility.

It takes approximately 12 minutes to lift the nodules off the seabed floor and transport them to the surface with the riser. While a nodule can be in production in less than 30 days, it can take up to six months to be processed and a product produced. The operation includes an adaptive management system containing marine hardware and cloud-based artificial intelligence.

“In the face of increasing demand for metals, we feel it is important to supplement metal supplies in a way that inflicts the least impact on the planet and people. EVs and renewable energy are a key part of the solution, but scaling these technologies will require hundreds of millions of tonnes of new metals. Polymetallic nodules represent the cleanest source of battery- grade metals on the planet and the best path forward. Our process reduces CO2 water use by 90%, and there are no tailings,” says TMC’s CEO and chairman Gerard Barron.

According to TMC’s website, “One nodule contains high grades of four key metals, meaning that four times less ore needs to be processed to obtain the same amount of metal. Nodules also contain no toxic levels of heavy elements, and the entirety of a nodule can be used, making near-zero solid waste production possible. Over 90% of the entrained sediment is expected to be separated from the nodules inside the collector and discharged behind it, with most sediment settling back to the seafloor within a few hundred meters.”

Some of the obstacles according to Wiltshire are that “they are mining 6.1 km down. The machine needs to work all the time and not jam. Hurricanes can happen. Companies can do it if they can do it in a profitable and ecologically sound way. Land-based mining does not have the same problems.”

A Belgian company named “GSR” is also planning to harvest polymetallic nodules in the CCZ. However, during a test in 2021, their nodule collection device became detached from the hose connecting it to the surface vessel. The device sank to the ocean floor and was later recovered and reattached four days later.

“There are lots of hurdles to make it profitable. To mine it successfully, the mine needs a steady reliable supply that they can count on. No major car company is looking to do deep sea mining, for example Tesla,” says Wiltshire.

Much of the opposition to deep sea mining is because of the possible ecological effects. “Regarding ecology, there is no such thing as zero-impact. We are using science-based evidence. Greenpeace and OPP exaggerate the potential for ecological disaster. The sediment plume is a significant risk, it may travel thousands of miles and rise two metres above the sea floor. A study is coming out on this soon,” says Barron.

Jeffrey Donald, head of onshore development at TMC says, “Opponents are formidable. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are prone to hyperbole. We take environmental science very seriously. We have environmental scientists working on this, who have gathered reams of data.”

According to Sarah King, head of oceans and plastics campaign at Greenpeace, “Deep sea mining is unnecessary. The industry has done a good job of greenwashing the positive aspects and benefits. Deep sea mining is not required for the transition to a green future. A small number of companies are set to profit from devastating impacts on ecosystems and Indigenous Peoples.”

Last March, a petition with over 1,000 signatures from 34 countries and 56 Indigenous groups was delivered to the International Seabed Authority (ISA). The petition called for a ban on the industry.

“We are calling for an immediate ban on deep sea mining because we need drastic changes in the way we manage our oceans. The threat of deep sea mining is huge. So, our measures to protect the ocean and the life within it must also be huge. My people have lived in and around the ocean for generations. It is who we are. We are the ocean, and we must act now,” said signatory Solomon Kaho’ohalahala, Hawaiian Indigenous speaker and activist.

Germany, New Zealand, and Switzerland have called for a moratorium, while France supports an outright ban. However, Norway recently indicated that it would offer permits for mining the seabed in their national waters.

Canada has announced a moratorium on deep sea mining in both national and international waters.

A joint press release on Feb. 9th from Jonathan Wilkinson, Minister of Natural Resources, and Joyce Murray, Minister of Fisheries, Oceans, and the Canadian Coast Guard, states Canada’s position:

“Canada does not presently have a domestic legal framework that would permit seabed mining, and, in the absence of a rigorous regulatory structure, will not authorize seabed mining in areas under its jurisdiction. The government of Canada has not taken part in the exploration of mineral resources in areas beyond national jurisdiction.”

“Seabed mining should only take place if effective protection of the marine environment is provided through a rigorous regulatory structure, applying precautionary and ecosystem-based approaches, using science-based and transparent management, and ensuring effective compliance with a robust inspection mechanism.”

A scientific paper published in the Current Biology journal estimates that approximately 5,500 new species of life live in the CCZ, and up to 92% have never been seen before.

Wiltshire says, “The problem in the deep sea is that we do not know exactly what we are going to affect. Hopefully, we are not going to wipe out the only thing that can cure a rare type of cancer. The problem is what life forms are there, how many are there, and are they located anywhere else in the world? How big is the area that will be mined? What is the impact? Are the species only in that area?”

One of the main things holding up deep sea mining is the lack of regulations for the industry. The ISA held talks in Jamaica from July 10 to 28 on creating a mining code. In July 2021, Nauru, TMC’s sponsoring state, triggered a loophole which required the ISA to establish regulations by July 9, 2023. This two-year rule required the ISA to “consider and provisionally approve” applications two years after they are submitted.

While theoretically TMC could start mining after the July 9 deadline without a mining code in place, Barron says, “We have the legal right to submit an application after July 9, but will not commence until the mining code is adopted.”

Investors appear to be losing their appetite for investing in the controversy plagued industry. TMC’s stock has lost more than 90% of its value on the Nasdaq exchange since going public in 2021, according to The Wall Street Journal. Stocks have plunged from $12.10 when it was first listed to approximately 80 cents.

In May this year, shipping giant, AP Moller-Maersk, sold most of its shares in the company. It now holds less than 2.3% of the company’s stocks, down from 9% in 2021, and plans to sell its remaining shares. Maersk signed an agreement with TMC five years ago to provide shipping services, receiving payment in shares. In 2022, a TMC representative said that Maersk did not have a vessel suitable for TMC’s mining operations.

In March, Lockheed Martin sold its shares in U.K. Seabed Resources to Norway’s Loke Marine Minerals.

Norwegian financial services company, Storebrand, has excluded four mining companies, including TMC, because of their new nature policy which furthers their commitment to “halting and reversing the loss of biodiversity.”

In their 2022 fourth quarter Sustainable Investment Review, they stated, “With immediate effect, Storebrand has excluded four companies in the mining industry. Storebrand will no longer invest in companies with mining operations that conduct marine or riverine tailings disposal, companies involved in deep sea mining, and companies that derive 5% of their revenues from drilling in Arctic areas that are considered especially vulnerable and valuable.”

Nautilus Minerals, a Canadian deep sea exploration and mining company founded in 1997, planned to mine a seafloor massive sulphide deposit off the coast of Papua New Guinea. Their Solwara-1 was the first deep sea mining project, but they went bankrupt in Oct. 2019. Prime Minister James Marape said that the country had “burnt almost PGK 300 million (approximately $120 million CDN) on a total failure.” Marape supported the establishment of a 10-year moratorium on deep sea mining projects worldwide. Papua New Guinea Minister of State-Owned Enterprises, Sasindaran Muthuvel, considered the country’s debt from the project “money sunk into the ocean.”

There has been interest in seabed mining since the 1970s. Time will tell whether it will become a viable option for battery minerals or if the industry will be hampered by the opposition arrayed against it.

Catherine Hercus is a freelance mining writer.

Comments