How to protect your investment: advice from the lawyers

There are plenty of issues that can come up and

motivate a government to change its policy.

Capital-intensive projects in foreign countries and long-term agreements in the mining industry can be subject to political risk and change that can impact investment. The protections available through investment treaties and the importance of structuring investments at the outset can help mitigate risk and protect international interests.

One of the key tools available to those involved in international mining operations is investment structuring to seek protection (and rights) under international investment treaties. Not only can investment structuring provide certain protections, but it can result in a company being able to pursue its rights with assistance from disputes funders or to utilize disputes funding so that the dispute is de-risked for subsequent corporate transactions.

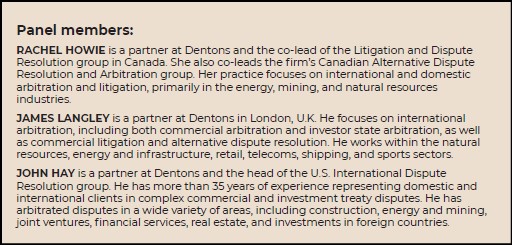

Recently, CMJ met with a panel of three lawyers from Dentons to discuss investment protection of capital-intensive projects in foreign countries, and long-term agreements in the mining industry.

Dentons’ expertise and experience in mining and natural resources goes beyond the law and extends to a deep understanding of the industry and how that should translate into legal matters. This article summarizes the key takeaways from that discussion. A detailed version of the discussion is available through a podcast on the Northern Miner website.

What is investment protection? And what do investment treaties protect?

Investment protections are protections and benefits to foreign investors under international investment agreements. They are usually multilateral or bilateral investment treaties or free-trade agreements that contain investment protections. The first investment treaties date back to the mid-fifties, but they became much more common in the 1980s.

They are intended to attract private investment in developing countries. They provide fundamental protection for investments as an alternative to local law that is inadequate to protect the investor, and they provide rules for arbitration under the treaty as an alternative to local courts.

To put it in context, there are probably over 2,300 different investment treaties in force today in the world. In addition to the procedural protection of an arbitration clause, they also have some substantive protections, such as most favoured nation treatment and national treatment, which prevents discrimination in favour of local entities when a foreign investor is making an investment. Other key protections include an obligation to provide fair and equitable treatment and a guarantee against expropriation without compensation.

Freedom to transfer funds and capital into and out of the country is also an important aspect of these treaties. The treaties also provide full protection and security against possible actions by the government. They cover investments by an investor from one country in the territory of another country. The investment is usually generally defined to include virtually any asset.

Why is investment protection important?

Investment protection protects the investor against the risk of state interference with investments. This can be a concern in mining because mining projects are long-term. They could span multiple governments and multiple elections in any given region. And even in states that are considered safer for investment, a government change because of an election or another regulatory shift that could see perhaps a new denial of a license for a critical minerals project that has obtained previous licenses, and thus a substantial amount of work and investment by the investor up to that point in time is wasted because of the possibility of regulatory and political risk and change.

If those investment agreements give the right to arbitrate disputes, they ensure that the investor is not necessarily required to act against the state in local courts where the outcome may be unpredictable or where the outcome might be political or where the courts might not be thought of as independent. Another important aspect is that these protections are additive to what can be obtained through political risk insurance from private providers or in contracts from governments or from the multilateral investment guarantee agency. The protections and benefits are outside of national laws, which mean it is very difficult, if not impossible for one state to unilaterally change the law to deny them.

Investment protections also provide foreign investors with more expansive protections if they must pursue a claim for a loss; the amount that they could claim and could be entitled to under an investment arbitration could be far higher.

At what cost?

Unlike private insurance that might have premiums to be paid, there is no cost to these protections.

That is a relatively new thing and of course a massive advantage for an investor in mining, for example. Local courts do not necessarily have an expertise in mining, but arbitration tribunals do.

To allow negotiations that oftentimes come up with a resolution, investment agreements are structured where the party bringing the claim must give a notice, and then there is usually a cooling off period before the claim proceeds. The benefit of this structure is that it might be enough to bring the parties to the table to really get a commercially fair deal.

How do states or governments commit to investment agreements?

In most cases, you seek the benefit of those agreements in countries where the regimes are not democratic to protect your investment. So how do those governments get into those agreements?

It is not an in an agreement between the individual company and the state, although that sometimes happens. It is a situation where one country has a treaty with another country where both countries are consenting to arbitration, and under that treaty, they agree that the investors from one of the countries into the other will have certain rights.

For example, Canada and Colombia have an investment treaty under which if a Canadian mining company invests in Colombia and the Colombian government does something that adversely impacts that investment, that investor has a right to bring an arbitration against Colombia. So, Colombia is bound to arbitrate.

These are bilateral investment treaties, but usually called investment protection and promotion agreements. States enter these treaties to incentivize investment from the other state. Despite exposing themselves potentially to claims from investors, they are also doing that in exchange for investment in the first place. Something that will be factored into the negotiations between the states is what protections one is prepared to offer to the other. The system can suddenly change, and one country might terminate a treaty (as was the case during NAFTA renegotiations), but eventually they may reach another agreement that satisfies all parties.

Why is this particularly relevant to the mining industry?

There is an exponential demand for critical minerals and rare earth elements that is expected to quadruple by 2030 because of EV and other green technologies. These are still capital-intensive endeavors, and they still require substantial investment at the outset. They have high production costs, they are long-term, and the investor might not see a profit for years after starting a new operation. Also, at that intersection of competing regulatory and political issues for governments are things like water and land use plans, taxation, royalties, mining permits, emissions targets, environmental areas of protection, and government interest and strategic and critical domestic supply. All of that could create a perfect storm where projects, in jurisdictions that might be politically unstable or even subject to just regular change through elections and change in government perspective, would be subject to impacts in a way that are detrimental to the investment.

Because miners doing business now need to make decisions on projects to meet demand in 2030 and beyond, it is difficult to predict where that political and regulatory perspective might be at that point in time. So, doing an investment agreement analysis and seeing what protections are or could be in place can help to protect them in the future.

You can expect all sorts of ways in which governments will seek to take a greater share of that investment. As an investor, you should never wait until something goes wrong to your investment to check whether you have treaty protection; you need to make sure you have that at the outset to avoid having to restructure your investment to take advantage of a treaty, which you generally cannot do after a dispute has arisen.

There are plenty of issues that can come up and motivate a government to change its policy. If a mining company is investing in a country that does not provide a great deal of protection through treaties, they can at the early stages of the project partner with another company, that would be the actual investor, from a country that has a better investment treaty with the host state.

How does investment protection interact with the risk around increased ESG scrutiny?

ESG has a more advanced regulatory regime in the more developed parts of the world. We are seeing provisions around ESG being introduced in treaties. It is quite a new thing. ESG in the context of mining has several different strands. One of the obvious things would be the environmental impact of the mining process itself. Then, the human rights related issues and the impact on local communities.

The G in ESG manifested itself in issues around corruption: we are seeing an increase in integrated companies operating projects out of subsidiaries or group companies. The parent company is a listed company in a jurisdiction where it is easier to bring claims. Also, when a country offers favourable benefits for investments in the renewable energy sector and then removes those or significantly reduces the benefits, the result can be a whole wave of claims against the state.

A relatively new phenomenon is the possibility that the treaty wording allows the state to bring a counterclaim against the investor in case of environmental issues for example.

So, there may be a situation where an investor has been successful in the primary claim against the state, but there is a counter claim that neutralizes the value of that. It is a growing area and will become more prominent as we see new treaties where it is easier to bring counterclaims.

Comments