Critical minerals: a panel discussion from PDAC 2022

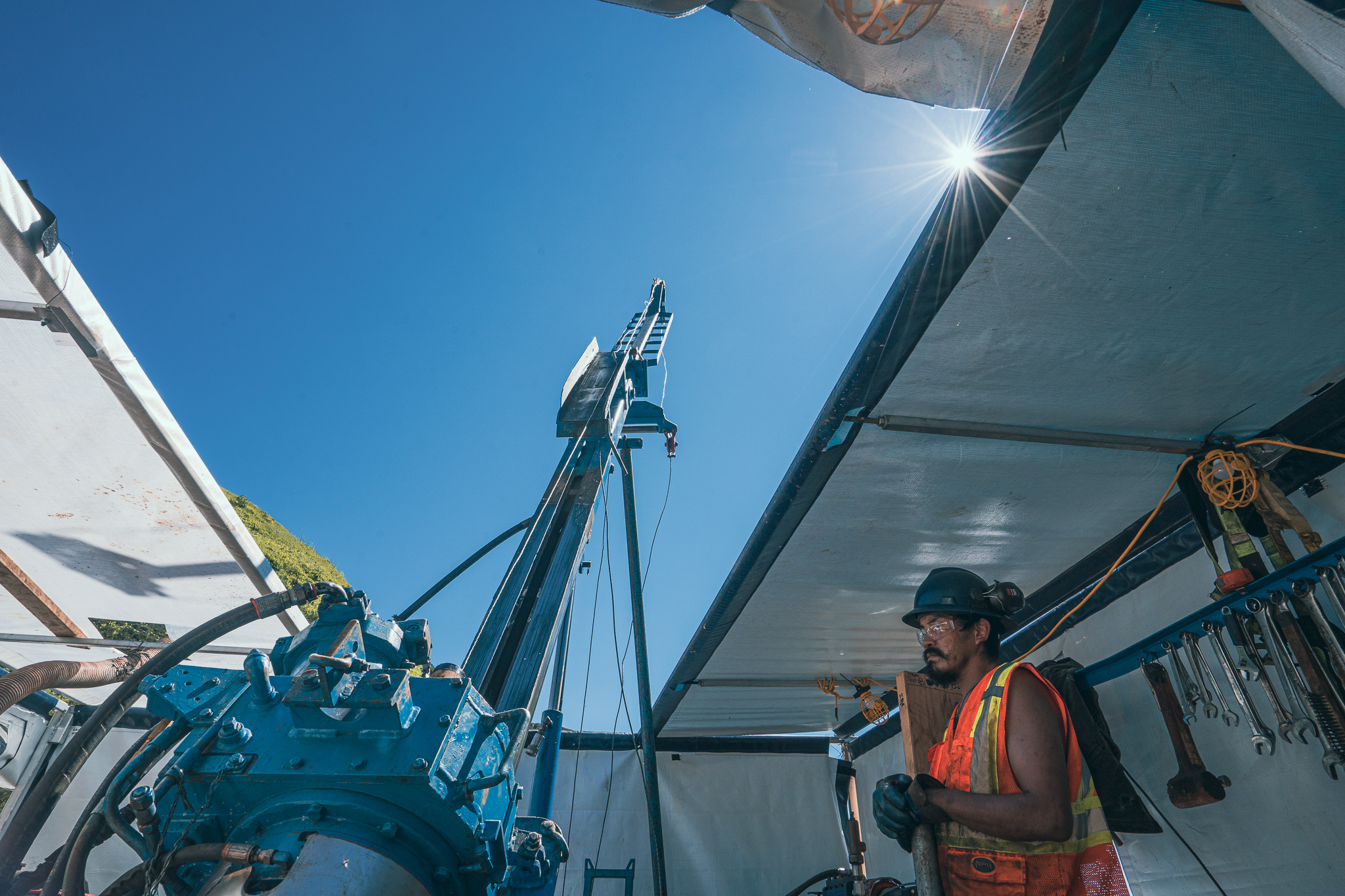

CREDIT: NOUVEAU MONDE GRAPHITE

The demand for battery materials could mean a paradigm shift for Canada’s mining and metals sector, one that could make the industrial revolution look like a lane change. There are four things we must build and do right now to be considered a serious player in the critical-minerals marketplace.

The global market for batteries is expected to grow by 20% annually for the foreseeable future – that is $300 to $400 billion in the next decade. We are in the middle of an energy and technology revolution, and the world needs what Canada has: critical minerals and raw materials, robust mining and processing expertise, and a government with a reputation for being business-friendly, fiscally sophisticated, with high standards for environmental protection, human rights, labour, and workplace safety.

Things are happening quickly in battery technology development, along with its manufacturing and distribution. There is a lot of excitement about what this opportunity represents for the industrial sector and the country. We want our share of the pie.

Yet for all its potential, Canada is late to the table. The net-zero train is pulling out of the station. There is a chance to get on board if we act now.

At this year’s PDAC conference, I was invited to join a panel discussion as part of the Capital Markets program. The topic was “A battery file push to net-zero industry: Call to action!” There was a good exchange of visions, positions, analysis, and advice from industry, government, special interest, and investors. All agreed the opportunity is immense, but the margin for error is very slim.

Here are four things we need to start doing today and the challenges we must face if we ever hope to maximize the opportunities the battery age is giving us.

ONE: Infrastructure. If we build it, will they come?

The overarching challenge is that we have two revolutions happening at the same time. One is the effects of climate change, pushing us to “go electric” at full tilt. Two is the magnitude of what must be conceptualized, built, and developed to make it happen. Both are heavily dependent on metals and mining, and on having the sector step-up in ways it never had to before.

Critical metals is a new industry for Canada, and it is requiring our sector to become something very different. Gold, iron ore, copper; crushing, grinding, flotation – we know those things well. Today, a traditional project to mine gold, for example, is a 7-to-10-year timeline.

Launching a new project to locate, mine, and process critical metals is effectively two major projects at the same time. The construction of the mine itself is often in a remote location. That means having infrastructure, transportation, and adequate living conditions long before shovels hit the ground. The second part is the process transformation that is needed for critical metals. We do not yet have the tools to build an industry like that. Taken together, the mine construction and unfamiliar processing methods translate into a lot of risk, like project inflation, delays we cannot anticipate, and cost overruns we cannot control. Not to mention the likelihood of a few failures because we are dealing with high-risk, new-process technology implementations and trying to adjust to unpredictable market shifts in supply and demand.

As mining consultants and engineers, we are constantly being asked to evaluate new processes and technologies for our clients. We see unique things that have never been built or done before. The problem is, when everything is new – and the net-zero industry is still a neophyte – we have no way to estimate what it really costs to produce the product. We cannot tell when the operation will begin to recoup the massive amounts of investment capital it will need and maybe even show a profit – something our clients are particularly interested in.

There are the ancillary costs we cannot anticipate. Waste products and their disposal. Transportation logistics. Canada prides itself on being a world leader when it comes to environmental protection and waste recycling. Managing the downstream, post-production issues could constitute an entire industry unto itself.

We agree that developing a critical-minerals industry could be an amazing opportunity. But our inexperience, our lack of local expertise, and especially the need to move so quickly all underscore the need for caution. Developing a new critical-metals sector will mean walking a very fine line between what government says we need and what the mining industry can realistically do.

The overarching risk is that the money spent on exploration today may not help in five years. Other options may materialize for cleaner energy and battery technologies that are less expensive or disruptive.

There is a lot of risk when you try to do new things. But we need to bring every tool we have to the game and invent a lot of new ones. Because we need to stop burning fossil fuels.

TWO: A workforce with the right skills

There is no substitute for knowledge and experience. In mining, processing, and distributing critical minerals for battery production, the world’s pool of technical expertise is small and largely concentrated in China. Now, we have clients who are comfortable mining and processing lithium to produce concentrates. But these concentrates are then sent to China, where they have the knowledge and technology to convert them into batteries. That is the part of the process where the most value is added, and that is part of the process where Canada lacks the most presence.

We have only a small portion of the expertise it takes, first to build the mines and the processing facilities, then to operate, fix, and maintain them. What is more, we compete with the rest of the world for people with the requisite skills. We like to think people want to come to Canada, but the remoteness of our mining regions is not always an inducement for experts who can work anywhere. And the COVID-19 epidemic has added another layer of complexity to recruiting over the past two or three years.

My colleagues on the panel at PDAC all agreed that the critical-metals industry is a rare and great opportunity. They also agreed that there will continue to be skills challenges.

The next divide is between government and industry. Their interests and goals differ. Government sees the skill shortage as an economy-wide problem, even the “most critical issue facing Canada’s industrial capacity right now.” Ottawa wants to see skills developed in various areas and says it is putting programs in place to support this. But government also wants private industry to take on the task of skills development. That can be costly. Both agree that young people are the third piece of the puzzle. Students need to be encouraged to learn different skills and choose different career paths if new industries are going to get the employees they need.

Looked at the right way, this could be a turning point for our industry. For decades, we have been working to improve everything about mining practices. We have done much to overcome its poor reputation in the last century, when the word “mining” was synonymous with environmental damage, sub-optimal safety standards, and disregard for Indigenous communities in the areas of its operations.

Today, young people need a reason to start seeing mining in a new way: as a problem-solver in the climate change challenge. Critical minerals are making a slew of new products and industries possible. Students, especially in the STEM fields, are excited to be a part of how the future is evolving. That enthusiasm is creating a lot of interest in minerals, batteries, and cleaner, more efficient sources of energy.

We are reaching out to develop stronger relationships with universities, hoping to attract people by sponsoring engineering projects, providing mentors and even internship possibilities. It is gratifying to see young people’s interest in mining and metals grow when we stress the positive things these products are helping our clients do, the solutions to serious problems they are helping them to find. They are excited to be associated with a company that is contributing to improving the environment.

Another consideration is that professional services, like those my company provides to the mining and metals sector, is a regulated industry. Mining professionals, their education, competencies, and responsibilities must be properly certified and are carefully controlled by professional and government licensing bodies. In some cases, it can take five years and more to become certified as qualified in a particular field. This adds still another layer of backlog that requires industry-wide consideration and time – which we do not have – to address properly.

THREE: An open chequebook

Major projects, like weaning the world off carbon-based power, cost a lot. Historically, when Canada built its transcontinental railway, its major highways or its automobile industry, the forces driving the projects had big buy-in from those who had the funds to support it. For what it will cost to scale-up a critical-minerals industry, the funding options are limited. There are the three orders of government and their strong credit ratings, and the big pension funds, which have traditionally been sources of mining financing. But this transformation is at a level that will require more than that.

Canada’s strong environmental protection, labour, and health-and-safety laws could shortlist us as a desirable partner for countries pledging to conduct their businesses in sustainable, UN SDG-affirming ways. Again, the challenge is in the newness. Companies and countries often must decide between what is best for their immediate survival and what may service them long-term. No one wants to spend more capital than they have to. Canada’s first-world policies place it at a disadvantage, at least for the foreseeable future, because of the cost of doing business here is high compared to those places with less stringent regulations.

Right now, there are several worthwhile, shovel-ready projects that could help take us in the right direction. They are left stranded because the companies cannot attract investors. Financial support from the federal or provincial government would go a long way to de-risking these projects, showing a vote of confidence that would encourage private investment.

The Quebec Plan for the Development of Critical and Strategic Minerals focuses on specific elements that have direct application to the battery industry. The province says it wants to move rapidly to support the right development proposals and has earmarked billions for that purpose. The federal government claims to favour a “partnership orientation,” saying it is willing to adjust its posture to make funds available in the right way; i.e., one that is right for Canada overall. It is optimistic about the level of interest other countries have in securing access to a safe, secure supply chain for critical minerals.

FOUR: Partnerships and collaboration

Monumental tasks need monumental resources and strategic thinking. Clean Energy Canada says the country needs to double the size of its electrical grid over the next 15 years. The needs of the mining and metals sector must be considered in this growth plan. Doing so efficiently and with any degree of reliability is next to impossible when we cannot predict how much electricity is needed, where or when.

The government of Canada says some of the most credible mineral resources are on Indigenous lands or close to them. For miners, the chance to improve relationships with native peoples is a mission for the age. The provinces need to be involved enthusiastically, having more opportunities to work in partnership with indigenous communities, building local industries with bright economic prospects.

Finally, we need to continue creating good communication and opportunities for industry partners to come together and collaborate. There is plenty to do. Working together increases the probability that we will move forward together in technology development, in community-building and in providing good employment prospects as well as successful businesses and investments for our stakeholders.

The call to action

At PDAC, the panel wrapped up discussion of the critical-metals-industry potential with each participant describing the progress they expected to see from the industry, first by 2025 and then by 2035. Few were optimistic for substantial advancements in the next three years, although all implied there were plans in the works.

By 2035, the prospects are much better. Government, industry, environmental advocacy groups, and investors recognize the need to do whatever we can to accelerate investment in critical-mineral production for the good of the country and the health of the mining and metals sector.

Let us start with a national battery strategy for the country and the industry that we can all support. Let us be willing to change how we have always done things for the possibility of doing them even better. Finally, let us continue to fuel enthusiasm, especially among bright, optimistic young people who are considering career choices, for what we in the metals and mining industry have always done: find exciting new solutions that make the world a better place.

Colin Hardie is national director, mines and metals and chair of the board of directors at BBA Inc.

3 Comments

Tim Kong

Don’t worry, be happy, Canada is a resources country, Canada has the Natural Graphite resources, US is innovative and has the technology and financial resources in the EV revolution. We simply export lithium and graphite to US.

Tim Kong

There are no Canada invented gasoline powered vehicles in Canada, there will not be Canada invented lithium batteries nor Electric Vehicles in Canada, they will all be American-made. Canada is a Natural Resources country, the EV revolution in US will induce economic prosperity in Canada’s mining industry without the risk and without uncertainties, it will create more jobs besides the traditional production of precious metals and base metals.

Tim Kong

There is already a graphite processing plant owned by Eagle Graphite located west of Nelson and north of Castlegar in southern BC, 1.5 Km west of Aben Resources’s Slocan Graphite project, the plant can produce 4000 tonnes of graphite annually. The facility is strategically located close to the US city of Spokane, Washington and the Canadian port of Vancouver, British Columbia, Eagle Graphite offers efficient and economical shipping of high grade material to destinations worldwide.