B.C., Tahltan Nation ink landmark consent-based agreement

On June 6, 2022, the Tahltan Nation and the Province of British Columbia entered into the first consent-based decision-making agreement negotiated under B.C.’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act. The landmark agreement provides an important precedent for government, industry, and First Nations as federal and provincial governments adopt and implement legislation incorporating consent-based decision-making in the project assessment and approval process.

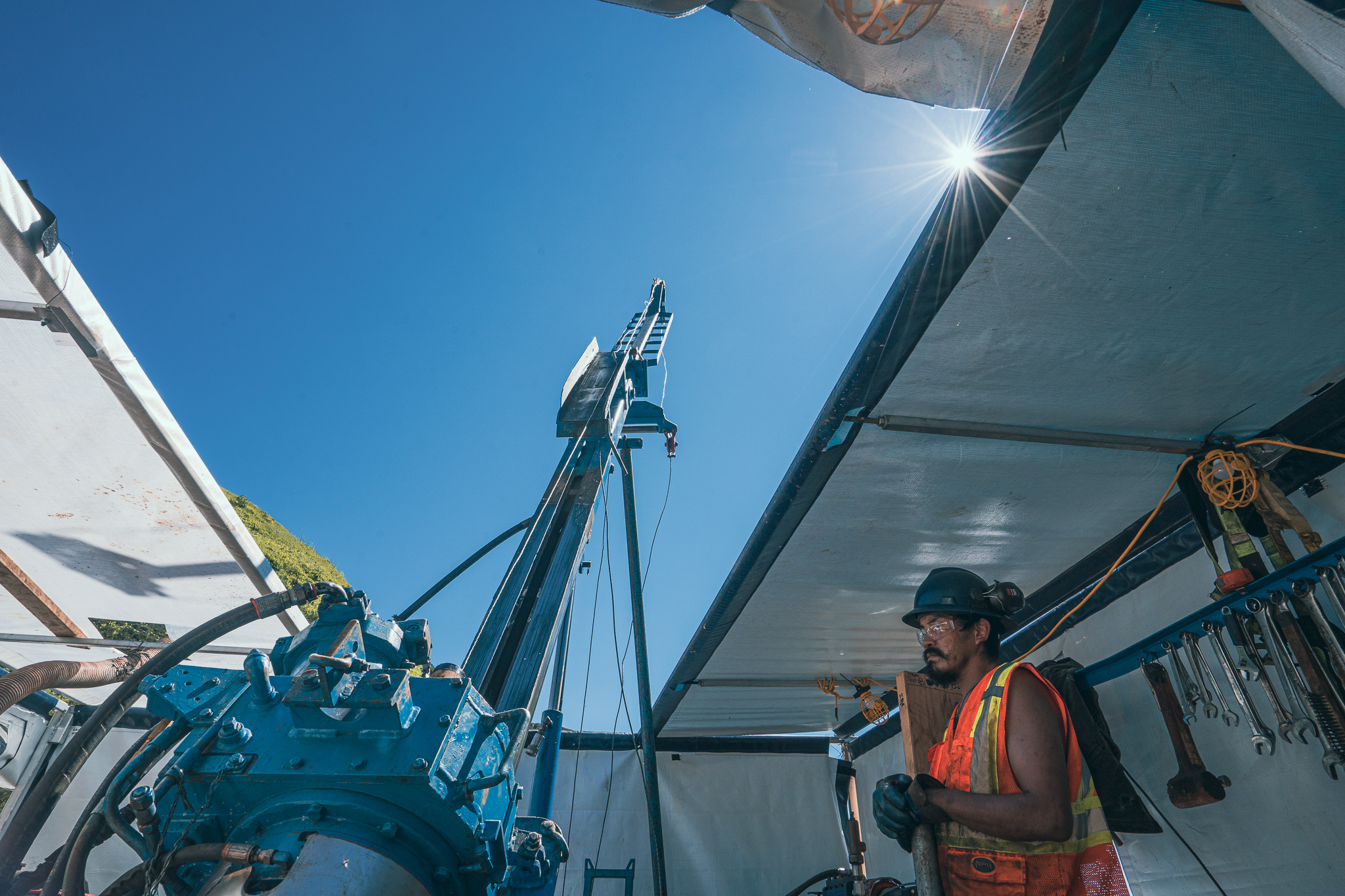

The agreement covers environmental assessment for the Eskay Creek revitalization project. The project involves reopening the historic Eskay Creek gold and silver mine that is located on Tahltan Territory, and which ceased operations in 2008. The project remains subject to reviews under both provincial and federal environmental and impact assessment regimes, with the agreement modifying the provincial process to allow for greater collaboration between the province and Tahltan central government (TCG).

UNDRIP, consent, and the duty to consult

The Declaration Act (which authorizes the agreement) was assented to on Nov. 28, 2019, making B.C. the first province to adopt the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) into law. UNDRIP is a non-binding international instrument that enunciates “the minimum standards for the survival, dignity, and well-being of the indigenous peoples of the world.”

Canada was one of four nations that voted against UNDRIP when it was first adopted by the United Nations in 2007. Among the Government of Canada’s concerns was a lack of clarity regarding an article requiring consultation to obtain “free, prior, and informed consent” (or FPIC) from Indigenous groups before making certain decisions that may affect their traditional territories. There was, and remains, a fear amongst some that FPIC provides a form of “veto” on government decision-making that would be inconsistent with Canadian law.

Pursuant to section 35 of Canada’s Constitution Act, 1982, government decision-makers owe Indigenous groups a duty to consult prior to making decisions that have the potential to adversely affect a proven or credibly asserted Aboriginal or Treaty right. The duty to consult requires that governments engage Indigenous communities in good faith with a view to understanding their concerns and, where appropriate, accommodating them by taking steps to avoid irreparable harm or minimize adverse effects. Often, regulatory approval processes play an important role in government’s discharging the duty to consult, as those processes may satisfy government’s obligations through participatory rights in regulatory hearings. However, Canadian courts long held that the duty to consult and accommodate does not provide Indigenous groups with a formal decision-making or veto power. Accordingly, some policymakers and legal experts were concerned that FPIC may alter Canadian law.

In 2016, a new federal government expressed full support for UNDRIP and adopted the act in 2021. Despite referencing FPIC in its provisions, the UNDRIP Act does not necessarily grant Indigenous communities and groups a veto over resource and infrastructure projects. The UNDRIP Act establishes the goal of obtaining consent following consultation – and the parameters for this consultation to be meaningful – rather than requiring consent before a project can proceed.

In contrast, British Columbia’s Declaration Act provides a means by which obtaining an Indigenous FPIC can be made mandatory. Section 7 of the Declaration Act allows the province to negotiate agreements with Indigenous governing bodies that require their consent before a decision is made. As further specified in section 7 of B.C.’s Environmental Assessment Act, a reviewable project subject to such an agreement cannot proceed without the Indigenous nation’s consent. Accordingly, by operation of these laws, such agreements may grant a veto power to Indigenous communities and groups that they would not possess under Canadian constitutional law.

The consent-based decision-making agreement

The consent-based decision-making framework outlined in the agreement modifies the standard British Columbia environmental assessment process in several important ways.

Seeking consensus

The agreement establishes a collaboration team composed of the TCG lands director and the B.C. environmental assessment office (EAO) project lead, as well as any individuals they designate, to seek consensus and promote collaboration between the province and TCG. This includes

> determining the informational and assessment requirements necessary to support the parties’ decision-making (s. 7.19)

> assessing the EAO’s draft environmental assessment report and draft environmental assessment certificate, including any conditions (s. 7.44).

The collaboration team, alongside the technical advisory committee, will also assist the parties in collaboratively reviewing the proponent’s application (s. 7.27).

Unique TCG assessment

In addition to the right to participate in the provincial environmental assessment process alongside other interested parties, TCG will conduct an independent “Tahltan risk assessment” and prepare a “Tahltan risk assessment report” to inform its decision on whether to consent to the project (s. 7.1). This report

will set out TCG’s conclusions with respect to whether the project is likely to cause significant residual and/or cumulative

effects to “Tahltan values” (s. 7.39). Tahltan values are identified

by TCG and may include archaeological sites, environmentally or culturally sensitive areas, wildlife, fish, plants, rivers, waterbodies, or other features important to Tahltan (s. 1.1).

Final decision

Once the EAO’s effects assessment is complete, TCG will decide whether to provide FPIC to the project (s. 8.2), which is required for the project to proceed (s. 4.3). While the minister can request that TCG reconsider its decision (s. 9.1), such a request does not fetter TCG’s discretion in reaching its final decision (s. 9.5). In other words, it is within TCG’s authority to say “no” to the project, and for that decision to be final and binding subject to reconsideration, judicial review, or dispute resolution.

Judicial review

The agreement specifically contemplates judicial review proceedings, with both TCG’s final decision and the province’s official decision being open to judicial review (ss. 12.1, 12.4). This means that TCG’s power to veto the project is constrained by standard administrative law principles and the TCG decision cannot be arbitrary, unreasonable, or the process procedurally unfair. The agreement further requires that both the province and Tahltan participate in any judicial review proceedings related to the project.

Dispute resolution

Where the agreement requires that the parties achieve consensus, and they are unable to do so, the collaboration team will refer the issue to a separate body of TCG and government officials (the senior officials table) (ss. 6.2, 10.1). If the senior officials table is unable to resolve the issue in a timely manner, they can refer the issue to a dispute resolution facilitator (s. 10.3).

The proponent’s role

The collaboration team and the parties are required to engage with the proponent in developing the process order (s. 7.21), reviewing the application (s. 7.31), and discussing the EAO’s draft environmental assessment report, the draft environmental assessment certificate, and the draft Tahltan risk assessment report (s. 7.45). However, the proponent is not part of the collaboration team or the dispute resolution process discussed above.

Implications

This agreement exemplifies a novel approach to project assessment and decision-making that others will likely seek to replicate across Canada, particularly for projects on the traditional territory of a single Indigenous group. Agreements between governments and Indigenous communities or groups that enable shared environmental assessment – and in some cases even require consent – are likely to become increasingly common.

The agreement demonstrates how consent agreements can integrate FPIC into the project approval process. While the government of British Columbia has stated that this agreement is “not a veto power but is rather the opportunity for consent to be provided,” it certainly appears to be a veto power of sorts. Tahltan decision-makers can say no, which is precisely what British Columbia’s environmental act allows under s. 7(b) and the Agreement confirms in sections 4.3 (“consent is required”) and 4.7 (which describes a “prohibition on the project proceeding without the consent of the Tahltan central government”).

Consent agreements can result in several benefits for project proponents, governments, and Indigenous groups, including advancing reconciliation and promoting collaboration, as well as attracting investment that accords to the highest of environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards. Consent agreements may also provide increased certainty and stability in terms of the process required for ultimate project approval. A consent-based process is arguably more transparent than a bilateral consultation process between government and an Indigenous community, in which the proponent may not have an active role.

On the other hand, a consent-based process may negatively impact timing to obtain a regulatory approval and may increase the likelihood that the project in question is rejected (based on the Indigenous group refusing to give consent), which could add a layer of uncertainty to some projects and deter private capital from investing in resource and infrastructure projects in Canada. The government of British Columbia hopes that later project permitting will proceed more quickly with the agreement in place due to robust Tahltan involvement early in the process, but the impact of such agreements on project timelines and investor confidence remains to be seen.

MAUREEN KILLORAN is is national co-chair, Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP. MARTIN IGNASIAK is a partner, regulatory, environmental, indigenous and land, Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP. SANDER DUNCANSO is a partner, regulatory, environmental, indigenous and land, Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP. SEAN SUTHERLAND is an associate, litigation, Osler, Hoskin & Harcourt LLP, and ASHLEY LIGHT is a law student, McGill University

Comments