Osisko dream team sets its sights on Windfall

Sunrise at the Windfall gold project. CREDIT: OSISKO MINING

Back in 2002, John Burzynski and Sean Roosen figured they’d paid their dues.

Burzynski had just finished up as country manager for Pangea Goldfields in Tanzania where he’d worked for nine years, and Roosen had worked for 14 years on contract across sub-Saharan Africa. Both men had been drilling off pre-existing mining camps they figured still had potential for good returns.

“This is what we intended to do in Canada in places people thought were exhausted, looking for large tonnage, low grade material left behind,” Burzynski says. “Nobody was doing that until we came along.”

Enter geologist and minerals explorer Bob Wares who liked the approach.

Before long he, Burzynski and Roosen were poring over an exploratory database for Quebec, eventually settling on a 230-sq.-km section of land in the Malartic-Cadillac area. There, four old mines lay “sitting by the highway, with the east Malartic mill sitting right on top,” Burzynski says.

Sold for a dollar by Barrick Gold the year before, a dormant mining camp other companies had worked and walked away from seemed like a daunting purchase for a new company with a couple hundred thousand dollars in the treasury, Burzynski mused. Despite their reservations, the newly formed Osisko Mining Inc. relieved the bankruptcy trustee of the property for $80,000.

“We then set to work on the surrounding land package, which by this time had showed us it really had the potential to be a very large mine,” Burzynski said. “People thought we were crazy.”

Today, Malartic hosts one of the biggest gold mines in Canada. Next step, though: relocate about a third of the town of Malartic at a cost of more than $180 million. Undeterred by the financial crisis, Burzynski and Roosen then raised $1 billion to build the Canadian Malartic mine and put it into production.

‘Osisko 1, meet Osisko 2’

In 2014, a failed hostile takeover bid by Goldcorp and an eventual $4.3-billion takeover by Yamana Gold and Agnico Eagle Mines saw $3 billion go out to shareholders. This came in the form of cash and shares spread across Yamana, Agnico Eagle and the newly named Osisko Gold Royalties, which retained a 5% net smelter return (NSR) royalty on Canadian Malartic.

“Over the next three to four years we’ve grown this into one hundred and thirty Osisko Gold royalties with a $2.3 billion market cap,” Burzynski says.

“We also kept a lot of our senior engineers, gold finders and top executives and relaunched Osisko Mining Inc.”

Core from Windfall, which is closing in on 1 million metres of drilling. CREDIT: OSISKO MINING

Osisko’s new focus: a deposit 115 km east of the town of Lebel-sur-Quévillon acquired in 2015 from Eagle Hill Exploration, bearing the optimistic name Windfall and today Osisko’s flagship project. Windfall hosts an indicated resource of 2.4 million tonnes grading 7.85 g/t gold for 601,000 contained oz., and an inferred resource of 10.6 million tonnes grading 6.7 g/t gold for 2.3 million oz. gold, using a cut-off grade of 3 g/t gold. This resulted from nearly 600,000 metres of drilling completed by previous operators on the project since 1997, and 414,000 metres Osisko drilled between October 2015 and March 2018.

Osisko’s drilling program will reach the 1-million-metre mark once its resource work is completed at the end of this year, says Burzynski. Drilling is underpinned by a $100-million budget with an expected drop in spending in 2020 during the feasibility and permitting phases, prior to construction. The mine has a capex of $400 million, according to a 2018 preliminary economic assessment.

Also fresh in the mining industry’s memory is Osisko’s announcement in July of four new high-grade zones discovered at Windfall’s Lynx deposit named Triple Lynx.

“What we discovered was mineralization of an entire corridor sitting directly below the main Lynx zone,” Burzynski says. He suspects Triple Lynx houses additional mineralized zones. “It’s been the character of this deposit, much like Malartic, that it’s always given us a little bit more than we’ve anticipated.”

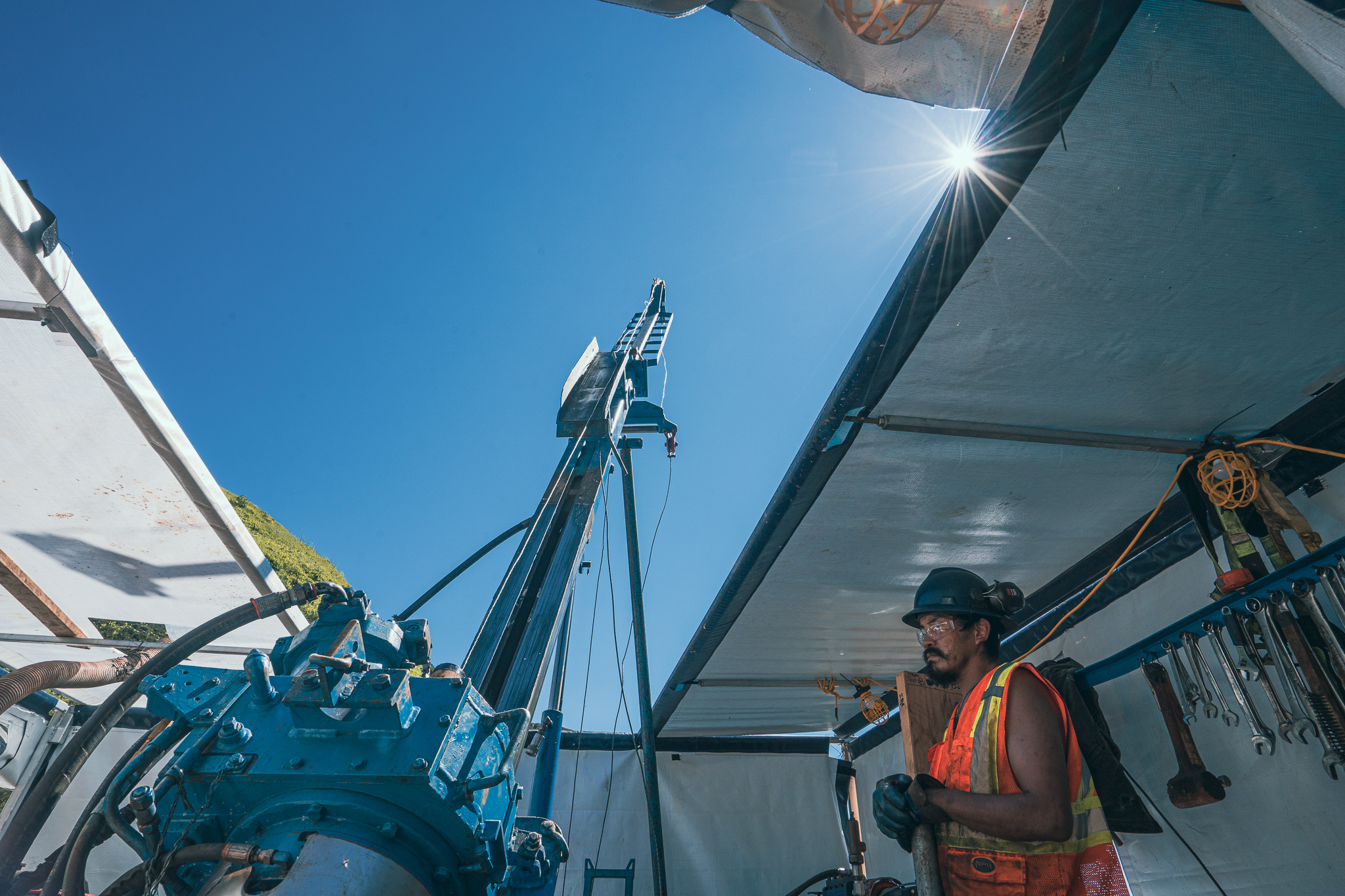

Overseeing the 23 drills currently in operation (two underground) is Windfall project manager Louis Grenier. “Mainly, we’re focusing on Triple Lynx, working on the northeast extension and on one of the deepest sections of the Lynx.” It’s also one of the most challenging jobs at Windfall, says Grenier.

“You have to keep in mind that behind the 23 drilling operations is a large crew.

We have people in long-term planning who look at the resource and where we have to be in the next two to three months.” A second, shorter-term planning crew is responsible for day-to-day relationships inside the drilling crews.

“In early 2017 we also employed three different companies who know the project is pretty large. We’re doing directional drilling at a depth of 2,000 metres and we’re confident each company has the capacity and experience to do that.”

Still, getting additional staff across most industries is hard, Grenier says. Osisko’s hope is that prospective employees will be intrigued by Windfall’s scope and its potential rewards. “Human resources is really, really important. We try to get them when they’re really young, train them and retain them as we go forward.”

More good news

Something Osisko had been anticipating came in early August with a private placement of $34.5 million led by Canaccord Genuity – critical for the additional drilling needed to define the Triple Lynx’s high grade mineralization. That includes one hole that intercepted 12 metres grading 47 g/t gold, “which is tremendous for a discovery hole,” says Burzynski.

Much depends on commodity prices, of course. “I’m an eternal optimist in terms of the price of gold. Gold is higher than it’s ever been in Canadian dollars so most Canadian producers are seeing the best margins they’ve ever seen.”

Osisko plans to finish the resource work and feasibility at Windfall by this time next year, and complete the usual 12-month permitting and 12-month construction cycles. Then, Burzynski says, “we could be pouring gold by mid-2022.

At that point I would expect the price of gold to be where it is or higher.” (Gold was at US$1,512.90 per oz., or $2,017.20, in early September.)

Someone else buoyed up by the good news is José Vizquerra Benavides, former senior vice-president of Osisko Mining, now president and CEO of O3 Mining, a $99.9-million spinoff company overseeing all ancillary properties outside the Windfall camp. Among these are Ontario’s Garrison mine, the Marban property west of the town of Val-d’Or and the James Bay portfolio formerly of Virginia Mines – all, says Benavides, overshadowed by Windfall’s success.

“Originally when we decided to buy all these companies and projects, we didn’t know which one was going to be the best one,” Benavides says. “But when we realized Windfall is a world class deposit we decided not to continue doing work in the other properties.”

Well-capitalized with up to $25 million in cash and marketable securities, O3’s shift is now entirely towards ancillary properties Quebec, notably Alexandria Minerals’ key in Val-d’Or land package acquired in August.

“We essentially have the entire eastern side of Val-d’Or,” Benavides says. “The centre part is mostly Alexandria Minerals’ (projects) while on the western part we have Marban.

What excites Benavides most, however, is the Airport zone south of Val-d’Or, which Alexandria explored and tested in 2015 because of similarities to high grade gold-quartz veins in the nearby Triangle Zone, now being advanced by Eldorado Gold, and on which Osisko Gold Royalties has a 2% NSR royalty. “That is an exceptional area,” Benavides says.

“We’re actually looking into a brown field at the Airport Zone, rather than starting from zero. Between the companies we have acquired to date from Marban to Alexandria, $72 million has already been invested in the ground.”

More key than tech expertise: wisdom

Much of the equipment smarts Osisko acquired in Windfall will be applied in the Airport zone. Of particular assistance: a handheld Vanta X-ray fluorescence energy dispersive spectrometer, or XRF analyzer. The portable XRF provides a comprehensive overview of mineral characteristics without undergoing a full slate of laboratory assays, Grenier explained.

“You point it to the core, wait thirty seconds and you get a full range of major elements,” differentiating, he says, between the different lithologies, including porphyry dykes, felsic volcanics and intermediate-mafic rocks. “With all this information on hand you’re able to make the right descriptions and the right decisions.”

Much of the credit for this belongs to John Burzynski, Benavides says. “John never stops reading and because of this is on top of every single new technology in the world. He is a strategist and technically impeccable.” Osisko’s CEO “is not afraid to try something new, to give us different ways to explore and a chance to try them in the field,” he adds.

“And if any of us has a new idea, we can share it with him. We don’t have to argue much; if we have a strong argument to begin with, he’s willing to try it.”

What is Burzynski doing when he’s not focused on mineral exploration? “More mineral exploration,” he chuckles.

That’s only partially true. In 2017, Burzynski led the extraction of a piece of Canadian history from the bottom of Lake Ontario. In 1959, the Avro Arrow was the first jet fighter designed and built in Canada – then promptly dumped by Ottawa in favour of the Bomarc missile program and an American jet fighter, the McDonnell F-101 Voodoo.

“It was a traumatic experience for the Canadian psyche. We pulled up one of the test models that is now on display at the Canadian Aviation and Space Museum. That’s us: explorers by day, explorers by night.”

Comments