Part III of our electric mines series: Collaboration key to innovation at Borden

Goldcorp’s Borden mine, near Chapleau, Ont. CREDIT: SANDVIK

If you were to visit Goldcorp’s Borden gold project, currently under construction near Chapleau, Ont., you would be hard-pressed to distinguish one supplier or contractor from another, or from members of Goldcorp’s own project team.

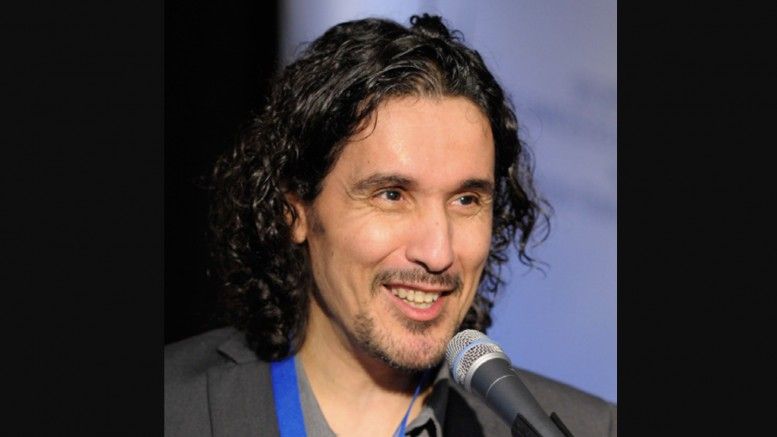

“Everybody that contributes to this project, we make sure that they become a team member so they’re not a supplier, they’re not a contractor,” says Luc Joncas, Borden project manager. “When they come to site they have all the same colour of coverall, same hats. We make sure people understand it’s all about being on the Borden team. Some of them now feel more like Borden employees than of their own companies!”

A battery electric boom truck,

manufactured by MacLean Engineering CREDIT: MACLEAN ENGINEERING

The effort to create a single, integrated team at Borden is all part of Goldcorp’s approach to encourage collaboration and make sure its ambitious project – which will be the first-ever modern, all-electric underground mine when it enters commercial production later this year – is successful.

From the start, the company knew that success at Borden would rest on finding partners as invested in its vision for an all-electric mine as Goldcorp itself.

That’s because some of the equipment needed to electrify Borden did not exist when the miner made the commitment in November 2016. Sandvik and MacLean Engineering, both leaders in electric equipment for underground mining, were brought on as official partners to provide non-diesel machines.

Joncas contrasts the partnership at Borden with the traditional transactional relationship between miners and suppliers where both sides seek to extract value from the other.

“In our case, we’ve really committed to partnership and collaboration,” he says. “Collaboration can create win-win situations for both parties.”

For the gold miner, the win will be to get the equipment and technology it requires in the timeframe it needs – and for all the components to work together to make an economic mine.

“A lot of these things can be done, but it has to be kept simple, effective, easy to install, it has to be a way that will make us perform in a profitable manner,” Joncas says. “So our goal is not just to build an electric mine but to build a profitable electric mine – as profitable as a diesel mine.”

For Sandvik and MacLean Engineering, the partnership will undoubtedly give them an edge in a market that is only expected to grow for environmental, cost and health and safety reasons.

“Goldcorp went out a few years in advance of everybody else globally, but we see all the other majors lining up. It’s coming,” says Stuart Lister, MacLean’s vice-president of marketing and communications.

“Right now all you really see is the Borden project, and some other examples like Kirkland Lake, but I think that the early 2020s is when we’re going to see that tsunami of that transition happening,” he said, adding that coming particulate regulations in the EU will hasten BEV adoption.

The project also provides a real-life testing ground and real-time feedback to develop their emissions-free product lines, says Dale Rakochy, Sandvik’s business line manager for LHDs and haulage trucks.

“It does help when you have real customers with real applications to sort of sit on your design board or offer critiques as you’re going down that design path,” Rakochy says. “There’s nothing that matches the experience from our actual customer operators who can help us be assured that when we develop something, we’re going to have a good reliable product that offers value to our customers.”

Having that testing ground also helps to ensure machine components are up to snuff as the OEMs look to build new, non-diesel based supply chains.

“Our traditional diesel driven environment has evolved over many years and all of our suppliers have also evolved over the years as the products have evolved,” Rakochy explains. “All of a sudden, we’re changing to a very non-traditional type of a drive system and at times, there aren’t products that are readily available that lend themselves to the compactness of an underground mining machine and the challenging environment.”

In late January, Sandvik announced the acquisition of Artisan Vehicle Systems, a private U.S.-based start-up specializing in BEVs for underground mining – another sign of its commitment to non-diesel technology.

Why electric?

For Goldcorp, the Borden project presented the opportunity to build a silent, invisible mine that would cohabitate nicely with the neighbours, including nearby First Nations communities and cottagers, says John Mullally, the company’s vice-president of corporate affairs and energy regulation.

“Borden Lake is 100 or so metres away from where we’re building the infrastructure and the project is on the traditional territory of three First Nations – Chapleau Cree, Chapleau Ojibway and Brunswick House,” he says. “That meant that it was an opportunity to build a mine that was highly inclusive of the communities around us, but also focused on being silent and being very conscious of our environmental footprint. This was really the context that prompted a lot of what we have then gone out and built.”

Mullally adds that aside from suppliers, Goldcorp also counts as partners both the federal and provincial governments (it’s received grants of $5 million from each for clean technology), all three First Nations and other mining companies with which it’s shared information.

Borden won’t be a huge mine: it is expected to average 2,000 tonnes per day over a 9-year mine life (probable reserves stand at 1.2 million oz. gold in 5.9 million tonnes grading 6.34 g/t gold). Rather than building an onsite mill, ore will be trucked to the Porcupine (Dome) mill near Timmins for processing.

Still, the difference in environmental impact is significant. Goldcorp expects Borden to produce 70% less greenhouse gases than a comparable diesel mine, eliminating 7,000 tons of CO2 per year.

And for workers involved in underground development at the $250-million project, the work environment is already far quieter, cleaner, cooler and comfortable than a diesel mine.

On a recent tour of the mine hosted by MacLean, Anthony Griffiths, product manager for fleet electrification at MacLean, said the difference was immediately observed by the guests.

“Everyone couldn’t believe how quiet it was and the temperature and the quality of air,” he recalls. “I don’t know how you would put a dollar and cents figure on that workplace improvement, but it’s certainly one of those things you notice right away.”

The benefits of electrification don’t end with environment and health. The reduced ventilation requirements will save 33,000 megawatts of energy per year, and combined with 2 million litres in diesel fuel savings, are expected to reduce operating costs by $9 million a year. Goldcorp will also spend less on maintenance of its battery electric fleet.

Those lower operating costs are important as battery electric vehicles have a higher upfront capital cost than diesel. Over the full life cycle, EV manufacturers say the total cost of EV machine ownership is comparable to diesel – and that’s before factoring in reduced ventilation energy, fleet maintenance and infrastructure requirements of an all EV mine, as well as operator productivity gains. As the technology continues to develop, there are already indications that in some cases, BEVs could make previously uneconomic orebodies profitable to develop, Griffiths says.

“In a couple of circumstances we’ve been approached by companies where the orebody was not economic with diesel equipment because of the depth of the orebody or the ambient rock temperature,” he says. “They’re now saying with battery powered equipment, we can do this.”

Equipment challenges

Goldcorp chose Sandvik and MacLean as its partners at Borden because of existing relationships with the suppliers, the size and type of equipment they offer, and their flexibility.

In terms of battery technology, Goldcorp also preferred opportunity charging through on-board chargers, as opposed to having to swap out batteries on mobile equipment, something both suppliers delivered.

The two OEMs also work together at Borden, including providing maintenance to any machine that needs attention, even if it’s not their design.

“One project, one team is the mantra up there, so as a supplier, our maintenance person is there to provide whatever maintenance is needed on that shift on any given day,” says MacLean’s Lister.

MacLean introduced its first battery electric vehicle, a BEV version of its popular scissor bolter, at MineExpo 2016. Since that time, the company has converted its complete line of 3 Series (8-ft.-wide) mobile underground mining equipment to battery power, from ground support to ore flow/secondary reduction and utility vehicles.

Sandvik is providing larger equipment to Borden, including 14-tonne load-haul dump (LHD) machines, jumbo drills and 40-tonne production trucks.

The company already has a battery electric jumbo drill and a tethered electric 14-tonne LHD – both in use at Borden. But it’s still working on a solution for the production trucks.

With the exception of the production truck, development at the mine, which passed the 360-metre-level late last year, has all been done with non-diesel equipment.

“The only exception is the trucking – that’s diesel and it’s only due to the fact that we did not find the right technology for our case,” Joncas says.

Despite recent advances in battery chemistry, the energy density in batteries is not yet sufficient for a fully loaded 40-tonne truck to haul material uphill out of the mine, he explains.

The production truck, which weighs about 40 tonnes and carries a payload of another 40 tonnes, has to climb 600 metres of ramp to get to the surface.

“Imagine the energy required in a battery to bring that mass of 80 tonnes from 600 metres below surface up to surface and repeat that five to ten times a shift,” Joncas says. “We’re asking too much from a battery truck right now.”

However, Goldcorp and Sandvik are working together to find a solution, says Goldcorp’s Mullally, with the delivery of the 40-tonne truck expected in the third quarter of 2020.

“Right now, we’re still running with Sandvik diesel trucks,” he says. “We continue to work iteratively with them around designing the model that’s going to work for us,” he says.

The other piece of equipment that’s been challenging is the 14-tonne LHD. Sandvik doesn’t yet offer a BEV loader in that size (it has one that is 6.7 tonnes), but it does have a tethered electric LHD. Tethered machines offer lots of power, but because they need to remain plugged in, have a trailing cable that limits their mobility.

As long as there’s only one face being developed at Borden, the mine works smoothly using tethered loaders. However, as more faces open up during production, the mine will need a loader that’s more flexible and mobile, Joncas says.

Designing an electric mine

The switch to electric from diesel affects more than just the actual machinery. It also affects the mine design and infrastructure. And that too is becoming an area of greater collaboration.

“Especially as we go down the electrification road, planning the electrical system underground will need to take into consideration how this equipment will be powered up and what kind of an energy draw will be required,” Rakochy notes.

For Canadian mines, a 600-volt electrical system is standard, but Goldcorp has made the decision to use a 1,000- volt standard at Borden, which will allow the mine to be more energy efficient and require fewer electrical substations.

While other jurisdictions in the world such as Australia and South Africa use a 1,000-volt standard, it is a departure for Canada. “I think we owe a lot of credit to Luc as the project manager who is willing to test preconceived notions or longheld assumptions – to test those by just asking, ‘Is this the best way to do that?” Mullally says.

Joncas says the decision has resulted in a faster pace of development and reduced costs.

“The substations can be placed further away from each other, so we were able to eliminate quite a few substations while driving the ramp,” he says. “We did not put any substations until 1,200 metres – that’s due to the choice of voltage, 1,000 instead of 600.”

While the suppliers don’t have direct involvement in the mine design, they are consulted on the design, especially as it relates to getting the best value out of the equipment they’re providing.

“Mining companies have really become open to including you in the mine design, the layout of the charging stations, the runs and heading sizes and all that,” Griffiths says.

Griffiths, who has 25 years of experience in the industry with MacLean Engineering, says this trend extends beyond Borden and is part of a change in the wider culture of mining.

“Before, you were given a specification for a type of machine – it had to do this and this and you competed on price and a couple of other things, but basically you knew what they wanted,” he says. “Now, the miners are willing to come to the OEMs and say ‘Can you do this? What do you think if we did do this?’ There’s a real sort of back and forth relationship going on with the development of the equipment.”

Comments