Stornoway’s First Diamonds

It’s not easy to over deliver, let alone deliver according to plan. But it’s what Stornoway. Diamond has a knack for doing.

In mid-July, the company started processing ore at Quebec’s first operating diamond mine ahead of its already revised schedule.

In mid-July, the company started processing ore at Quebec’s first operating diamond mine ahead of its already revised schedule.

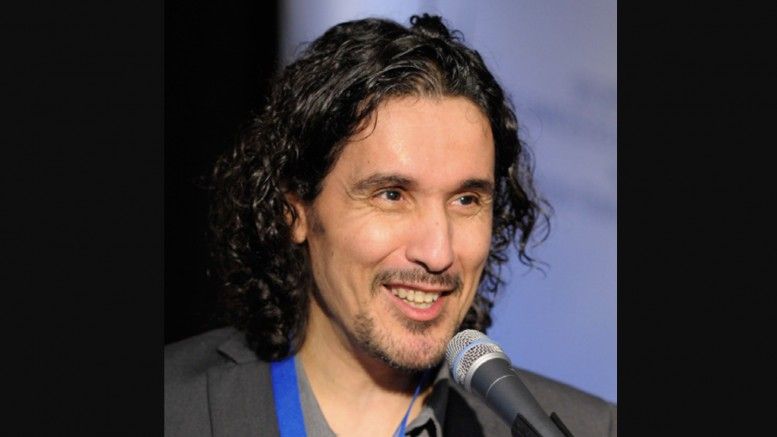

“There’s a huge amount of human capital that goes into bringing any mine into production – not just time and money. So seeing it happen, and it is happening under the best circumstances, [means] we are doing very well. We’re ahead of schedule, we’re below budget … it’s a terrific experience,” Matt Manson, the company’s president and CEO, says in a phone interview.

The Glasgow native, who became president in March 2007 and CEO in January 2009, notes Stornoway chose ore processing as the “moment to celebrate” the achievements at Renard. “It really marks the end of a 15-year journey of huge amounts of effort in exploration, development studies, permitting, financing and construction.” Ashton Mining of Canada and Soquem – the mining exploration arm of the Quebec government – found the diamond deposit in 2001. Stornoway acquired half of the project through its purchase of Ashton in 2007, and the rest from Soquem in 2011.

Despite the early bumps in sketching out Renard’s economics, Stornoway proved up the project’s potential and nailed down financial and local support. It has since exceeded its construction goals.

Despite the early bumps in sketching out Renard’s economics, Stornoway proved up the project’s potential and nailed down financial and local support. It has since exceeded its construction goals.

Back in February, the miner re-baselined its schedule for construction. It anticipated ore processing would kick off in September, with commercial production beginning by year-end 2016, roughly five months ahead of its previous plan. This revision lowered Renard’s estimated start-up capital to $775 million, from $811 million earlier.

In July, Stornoway processed 10 weeks ahead of the re-baselined target and seven months ahead of its estimate.

Buildings at the Renard mine site.

Manson attributes this to three factors.

The first is contracting and procurement.

“We’re the only mine under construction in Eastern Canada, and that’s a big construction market. We were able to expedite the process of finding preferred vendors and contractors,” he says.

Given that the company built Renard during the downturn in global mining, it benefitted from minimal lead times on equipment and material delivery. “Everything was immediately available to us,” Manson says. For example, the 2011 feasibility estimated an 18-month lead time on Caterpillar equipment, which Stornoway received in a few weeks.

Second, the company’s contractors and employees were efficient and more productive than expected, Manson says, “because we had the best teams.” Third, when Stornoway completed the original schedule as a junior looking to raise $1 billion to build a greenfield diamond mine, a lot of risks in the time line never materialized, Manson notes.

Days after closing a $946-million financing, Stornoway started construction at Renard on July 10, 2014.

In March 2016, the company updated the mine plan, extending Renard’s life by three years to 14 years. The extension came from a 25% increase in reserves.

Based on open pit and underground reserves of 22.3 million carats (from 33.4 million tonnes grading 0.67 carat per tonne), Renard should produce 1.8 million carats a year during the first decade.

Life-of-mine operating costs should average $56.20 per tonne, or $84.37 per carat.

Meanwhile, Stornoway will focus on reaching commercial production. While the executive does not expect to re-forecast Renard’s year-end target, analysts project that commercial production should start two to three months ahead of plan.

As of July 13, the miner had stockpiled 1 million tonnes of ore to support the ramp up. Michael Parkin, an analyst at Desjardins Capital Markets, points out that the re-baselined schedule expected the stockpile would reach 800,000 tonnes in September. Higher stockpiles show mining from the pits is “going well,” he writes.

Stornoway will source ore for 2016 production from the Renard 2 and Renard 3 pits, and supplement this with the stockpile if needed.

The operation should process 2.2 million tonnes a year, or 6,000 tonnes per day, before expanding to 2.5 million tonnes a year, or 7,000 tonnes per day in 2018. This would coincide with underground mining at R2.

The plant should hit full production – described as 2.2 million tonnes a year at 78% plant use – within nine months, or by March 2017.

“We are comfortable with the project to date,” Parkin says. The “biggest remaining risk” is reconciling the resource to see how the grade and average value per carat compares to the block model, he adds.

“We’re not going to declare success on this project until we’ve gone through the ramp up and the resource is reconciled correctly.” He adds that the latter would take several months.

The March 2016 reserve includes four kimberlites: Renard 2, Renard 3, Renard 4 and Renard 65. At the time, the weighted average price of the reserve was $209 (US$155) per carat.

Stornoway intends to sell all of Renard’s diamond production by tender sale in Antwerp. First sales should occur in January 2017.

Along with being ahead of schedule, the company has received nearly $83 million in proceeds, after 97.5% of its warrant holders exercised their 90¢ warrants to buy 91.9 million shares before the July 8 expiry date.

“We have a lot more cash on the balance sheet than we expected to have,” Manson says. “That gives us a lot of financial flexibility as to what we do with the cash flow when it starts.”

This Special Report was provided by Salma Tarikh, a staff writer with CMJ`s sister publication The Northern Miner.

Comments