WILLIAMS LAKE, B.C. – Two very different scenes played out on opposite sides of the building hosting the public hearing on the proposed New Prosperity mine in the hours before the hearing got started.

On one side, the City of Williams Lake put on a barbeque for project proponent Taseko Mines (TSX: TKO). Wearing blue scarves to show their allegiance, supporters chatted with each other and the media about what the huge copper-gold mine would mean for the small town. Taseko executives, representatives from the city's business community, and employees from Taseko's nearby Gibraltar mine spoke of cautious optimism, quiet but strong support, and crucial economic benefits.

In the park on the other side of the building, chiefs and members of a dozen First Nations drummed and sang, before a roster of speakers railed against the proposed mine. They spoke of the irreparable devastation the mine would bring to an area heavy with spiritual and cultural significance. They spoke of poisoned salmon, displaced grizzlies, disrespect for established First Nations' rights, even of "cultural genocide".

Then the two sides met.

Carrying placards with messages like, "Chilcotin gold is more valuable in the ground" and "Our fish = Our wealth", the anti-mine group slowly and deliberately made its way into the quiet auditorium. Taseko's team was arrayed on one side of the stage. The panelists for the hearing sat centre stage, facing the auditorium seats, their staff seated on the other side.

When everyone was in place, the protestors started drumming and singing. Their demonstration and blessing lasted almost 10 minutes. When it was done, protest leader Cecil Grinder shook hands with everyone on the stage, including those from Taseko.

The appearance of calm mutual respect belied tensions that have been building for 17 years.

New Prosperity is a new take on a proposed open pit mine that the federal government turned down in 2010. That result came 15 years after Taseko started advancing the property towards a development decision.

There's a small lake adjacent to the deposit, known as Fish Lake or Teztan Biny. Since the planned pit ran almost to the edge of the lake, Taseko originally planned to drain Fish Lake to ensure pit stability.

Taseko knew draining the lake would be contentious but still thought its proposal was reasonable. Teztan Biny is small, covering 110 hectares and averaging 3.5 metres in depth. There are 13,000 lakes of similar size in the Caribou region and the company planned to create a new lake on the other side of the tailings facility in recompense.

Building an open pit mine necessitates adverse environmental impacts. In Canada, those impacts are green lighted if the benefits expected to flow from the mine outweigh the damage. Prosperity at that time was expected to create 2,000 direct and indirect jobs in a region struggling with mill closures, unemployment, business and consumer bankruptcies, and a population exodus.

But Teztan Biny is important, too. Local First Nations say they have fished the lake and hunted and gathered in the area for generations. They also argue that the area holds spiritual significance as a gathering place in times of turmoil and that the mine, however developed, would poison vital fish habitats downstream.

The provincial government decided the benefits did outweigh the impacts and approved the proposal. The federal government disagreed, blocking development of the $815-million mine. In announcing the decision Jim Prentice, then federal Environment Minister, said the review panel report was "…scathing in its comments about the impact on the environment … It was, I would say, probably the most condemning report that I have seen."

Nevertheless the feds left the door open, saying said the government was not opposed to the idea of mining the deposit if another plan could be developed that mitigated the impacts on Fish Lake.

That is what Taseko did. The New Prosperity proposal outlines an open pit mine that saves Fish Lake by spending an additional $300 million to develop a pit that remains stable despite its proximity to the body of water.

In his opening address to the review panel, Taseko senior vice-president of operations, John McManus, pointed out that his company has done what it was asked to do.

"The government of Canada made it clear that it was not opposed to the mining of the Prosperity ore and that we could submit a new project proposal that addressed the factors that gave rise to the finding of significant adverse environmental impacts," McManus said. "That is exactly what Taseko has done."

McManus also highlighted the magnitude of Taseko's efforts.

"The significant and very extensive redesign of the project represents, in Taseko's submission, one of the most profound accommodations of aboriginal rights ever undertaken through the regulatory process," he said.

However, a significant and profound accommodation is not what First Nations see when they look at the New Prosperity plan. Speaking at the pre-hearing rally, Grand Chief Stewart Phillip said the new proposal is worse than the original and that Taseko knows as much because the original plan included a similar idea – dubbed Option 2 – that Taseko said at the time was infeasible and created more potential for environmental harm.

"Nothing has changed – this proposal is just as bogus, just as ugly, just as bad as the first time around," Phillip said. "I remember being in the hearing room when Taseko officials themselves described this particular option as being more destructive and devastating than the first option they were proposing. Now they're put a lot of makeup on it and they're saying this would not devastate and destroy Teztan Biny, but we know differently. The science is clear. This proposal would kill Teztan Biny and would destroy the environment around it and completely obliterate the indigenous people's land. We are all here to say one thing: there is absolutely no way we are going to allow this proposal to be approved."

Taseko has responses to those comments. First, Option 2 was infeasible at the time because metal prices then did not support spending the additional $300 million needed to save Fish Lake. They now do. Second, saving the lake creates the potential for harm to come to it, while draining the lake eliminates that potential by eliminating the lake. That is why Option 2 was described as creating the potential for additional harm.

At the rally, however, First Nations and other Prosperity protestors from near and far were not interested in discussing such details. The only topic of import to them was the destruction a New Prosperity mine would bring to the Fish Lake area, which sits 125 km west of Williams Lake.

"We unequivocally reject the New Prosperity mine proposal," said Chief Percy Guichon of the Tsi Deldel Nation south of Williams Lake. "We cannot accept this mine in our territory because of the devastating long term impacts that it would have on our culture, on our ability to practice our traditions in that sacred area."

Guichon continued, saying that Taseko has "never engaged in meaningful consultation" with First Nations but has only tried to "divide and conquer" in its "pursuit of the almighty dollar".

Language of that sort led to heated verbal clashes in the previous Prosperity hearing. This time around, supporters of the New Prosperity project tried to remain calm as the hearing approached, but anxiety over false claims and outside influences was apparent.

"It's been incredibly frustrating because people are basing their decisions not in fact and science but in emotion," said Jason Ryll, president of the Williams Lake Chamber of Commerce. "The misinformation is frustrating. And I think that unfortunately it seems to be a project that professional protestors are rallying behind for their own benefit, not for the benefit of the people they are supposedly representing."

Ryll believes Ne

w Prosperity is "critical" to the long term stability of growth of Williams Lake and the surrounding region, where the population is in decline because of a lack of employment. Ervin Charleyboy agrees. Charleyboy was chief of the Tsi Deldel for 20 years until 2010 and led the charge against the original Prosperity proposal.

After Taseko redesigned the project to save Fish Lake, Charleyboy changed his stance. He now thinks the economic opportunities outweigh the environmental damage – and he thinks local First Nations have been fueled to fight the mine by environmental activists who do not have his people's best interests at heart.

"There's no jobs here – a lot of our young people live from welfare cheque to welfare cheque," Charleyboy said. "It's no way for people to live. And where are our people going to be if it's a no? All these environmentalists who are challenging this proposal, if they win we are the ones that are going to be suffering the consequences, still living welfare cheque to welfare cheque and seeing no future for our kids."

Like Ryll, Charleyboy is frustrated by the misinformation he hears regularly from the anti-Prosperity camp.

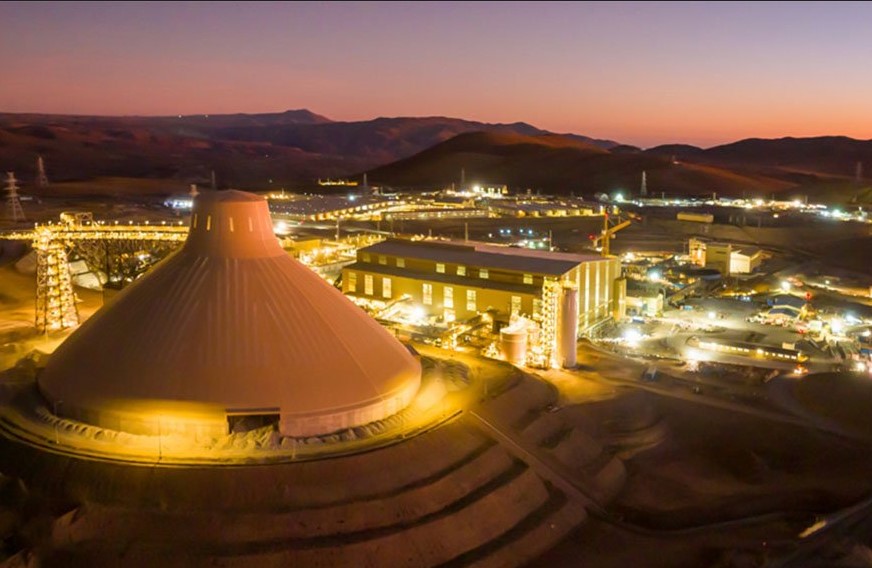

"Everybody says it's going to ruin our salmon and all that, but look at the Gibraltar mine," he said, referring to Taseko's operational copper-gold mine 60 km north of Williams Lake. "It's been there since 1973 and everything in that area runs into the Fraser. Same with the Mount Polley mine and the Highland Valley copper mine – all these mines have been there for years and everything flows into the Fraser and nobody's died eating salmon yet.

"The chiefs are being fed wrong information about mining," Charleyboy continued. "These big city environmentalists like the Sierra Club, they don't know what life is like in the Chilcotin. Young people are crying out for jobs and this would be great for them, but by protesting all these things, the whole world is passing us by."

Underneath the fight over New Prosperity, however, lies a much bigger battle: the war over aboriginal land rights. That fight underpins the New Prosperity proposal both theoretically and practically, as the project happens to sit on lands involved in the most significant aboriginal land claims court case in Canada.

The Williams case, as it became known, pitted the Tsilhqot'in First Nation against the Crown in a battle for title to a 4,380 km2 package of land in the Caribou Plateau. Faced with proposed forestry activities, the Tsilhqot'in argued for their right to full title to the land based on their long time presence in and use of the area.

In 2007 Justice David Vickers of the BC Supreme Court in his decision found the Tsilhqot'in have a right to hunt and trap fish and birds and trade furs throughout the 4,380-km2 area, which includes the Prosperity project. Justice Vickers said he could not declare aboriginal title to the entire area but he came close, saying he would have found for Tsilhqot'in title to part of the land package if that option had been presented. (Prosperity is outside of that smaller area.)

The case remains the only time a court has granted rights over a parcel of land to a particular First Nation. The BC Court of Appeal upheld the landmark decision; it is now before the Supreme Court of Canada. That court will grapple with the central issue around indigenous rights in Canada: What land rights do First Nations hold today over the lands they controlled before the Crown asserted sovereignty?

Before that question has been answered, Taseko wants to build a mine on the very lands the Tsilhqot'in believe they own.

It means the foundation of the Prosperity debate – whose land is it anyway? – is incredibly fraught. And since the New Prosperity panel is charged with considering all mine impacts, including those to First Nations, the hearings cannot sidestep this contentious and unresolved issue. In fact, the question of title could highjack the proceedings.

Indeed, in his opening remarks to the panel Chief Russell Myers Ross of the Yunesit'in First Nation spoke first to the question of title.

"There is no time in our history when we've actually had a settler government that has acted as though it indeed needed our consent to come into our lands, so this is a matter of justice," Meyers said. "It's important that we envision what we want out of this, which is to have a nation-to-nation relationship that's respected, that we're seen as a nation that has land and deserves respect."

The outcome for Taseko and the New Prosperity proposal remains very unclear. What is clear, however, is that the panelists will hear about much more than groundwater seepage and grizzly bear impacts over the next month and that the decision – which Prime Minister Stephen Harper will make, based on the panelists' report – will carry significance that reaches far beyond Taseko.

To read more Northern Miner articles, click here

Comments