Seeing the Light

Earlier this summer, 15 mine rescuers in three teams responded instantly to the call from the 1,000-m level at Vale’s Stobie nickel mine in Ontario. They were at the accident scene within 80 minutes but, sadly, not in time to save two miners crushed when a run of muck tore loose in the Number 7 ore pass. The would-be rescuers were from a pool of some 60 people Vale has trained in accident response, but when the tragedy struck, their very best team was hours away, completing in a provincial mine rescue event at nearby Marathon. It was a bittersweet time for the elite Vale rescue squad, as two days later they came away overall champions. That weekend, fellow competitors and spectators wore black ribbons in sympathy for the two lives lost.

Tragedy in the mine workplace is always a possibility, and sometimes, as at Stobie, a reality. But it is far less so today than in decades past, as the efforts of lawmakers, labour and corporations turned the tide on decades of safety neglect, and better science and technology improved everyone’s chances of success should disaster strike.

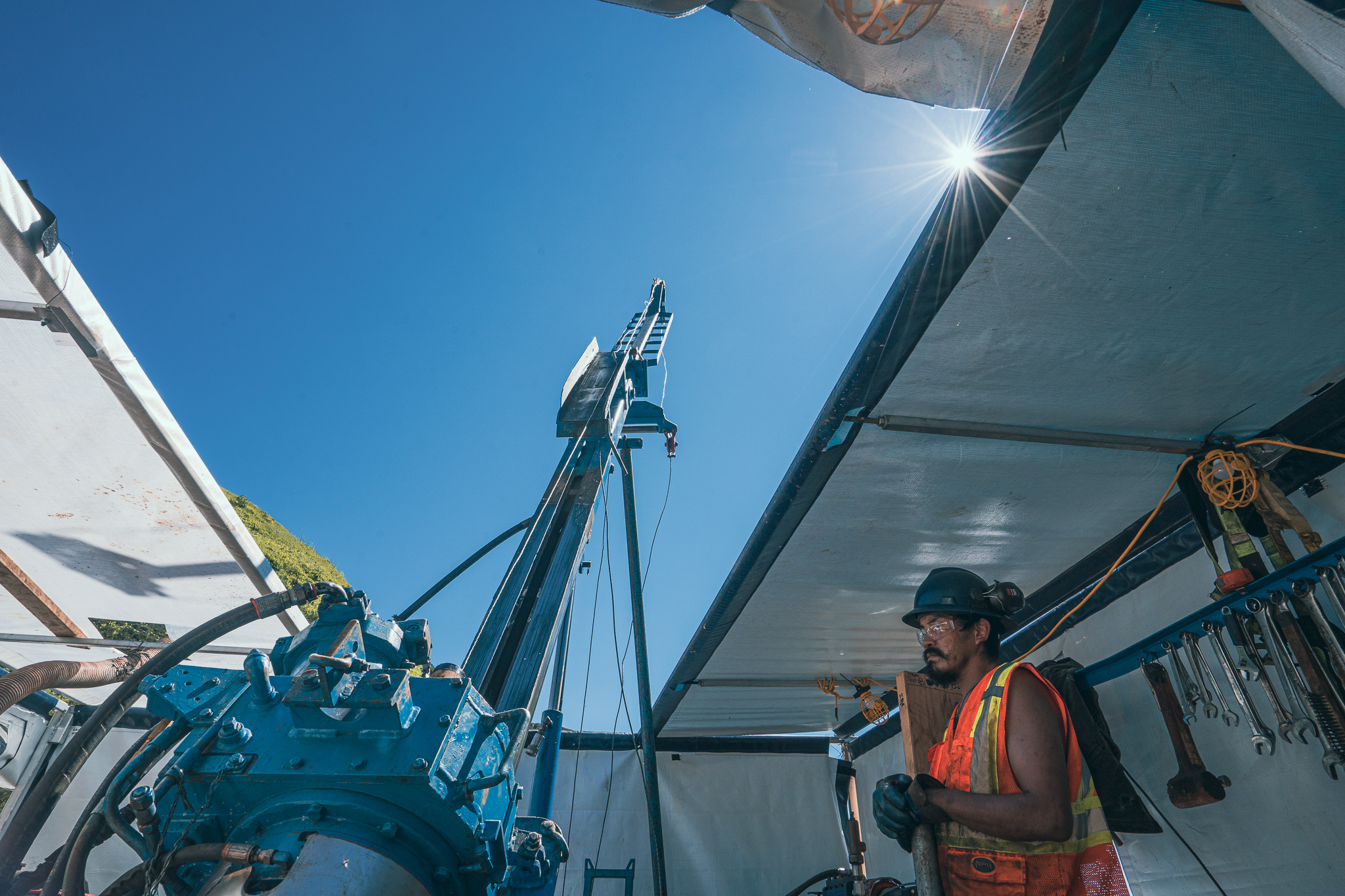

If it does, trapped and injured miners know that their own rescue teams – often the men (and sometimes women) they work with every day – are ready to risk their own lives to get them out. And it’s the same all across the country as dozens of other Drägermen, as they are known after their German-made breathing apparatus, will be on standby should a rescue campaign stretch into days, or even weeks.

It was Ontario’s Hollinger Mine fire in 1928 and its 28 lost souls that was the catalyst for a provincial Royal Commission and a call for the Department of Mines to set up a mine rescue organization. Every province has since followed suit (but there is no national oversight body in Canada).

Mines call for volunteers among their workers to serve as rescuers, and spend considerable time and money training and drilling them. For mine managers and directors, it’s not really an option; committing resources to build a rescue team gives them some assurance, corporately and morally, that they’re prepared to help save lives and property.

Competitions like the one in Marathon actually play a big role in a team’s readiness and performance. They’re a source of intense rivalry among neighbouring mines. Coming home with a trophy is a big moral boost for the workers, and badge of corporate honour.

“The whole premise is to check their capacity without having a real emergency,” says Peter Bengts, Chief Inspector of Mines for the NWT and Nunavut Workers’ Safety and Compensation Commission, which has organized the northern event since 1997 after inheriting the event from the Territorial Mines Accident Prevention Association.

Mining towns across Canada host these trials every year, and North of 60 Yellowknife hosted the pan-territorial Mine Rescue Competition. Six teams from five mines in all three territories squared off to see who was best at fighting fires, staging rope rescues and solving mock underground disasters in a timber-and-burlap mock mine. (The winner: BHP Billiton’s Ekati team, for the eighth time in the past 12 years.)

Earlier this year, Saskatchewan’s Mosaic potash mine successfully put its rescue readiness to the real test. At 3 a.m. on January 30, a fire 800 metres below surface put the lives of 70 miners and contractors in peril. Teams of mine rescuers, working in rotation, extinguished the fire and led everyone to safety, without injury, in 24 hours. They survived in well provisioned, air-tight underground refuge stations, had continuous voice communication with the surface, and knew their rescuers were on the way.

That was a textbook rescue. It barely registered on media screens, because it ended as it should have: quickly and with no loss of life.

But no mine rescue story can beat the astonishing saga that began August 5, 2010, under Chile’s Atacama Desert, when a rockfall trapped 33 men at the San Jose copper-gold mine.

Some 17 days later, when desperate rescuers drilled into their underground tomb and retrieved the tattered note that read, “We are fine in the refuge, all 33 of us,” the world’s mining network, including Canada’s, pooled their best brains and machines in a fevered race to drill a shaft wide enough, with pinpoint accuracy, to enable an almost impossible rescue.

Then, 69 days after it began, an estimated billion television watchers around the world cheered as, one by one, the men emerged unscathed from a Jules Vern-like escape capsule named “Phoenix” into the light and the deep embrace of a wife, or child, and the country’s president.

While the Chilean rescue is really a story of modern technology brilliantly applied, the reality of mine rescue is far less dramatic. So across Canada and around the world, small teams of volunteer heroes will keep on training, knowing that if they’re put to the test, they too can lead their friends back into the light.

Comments