Quick Turnaround

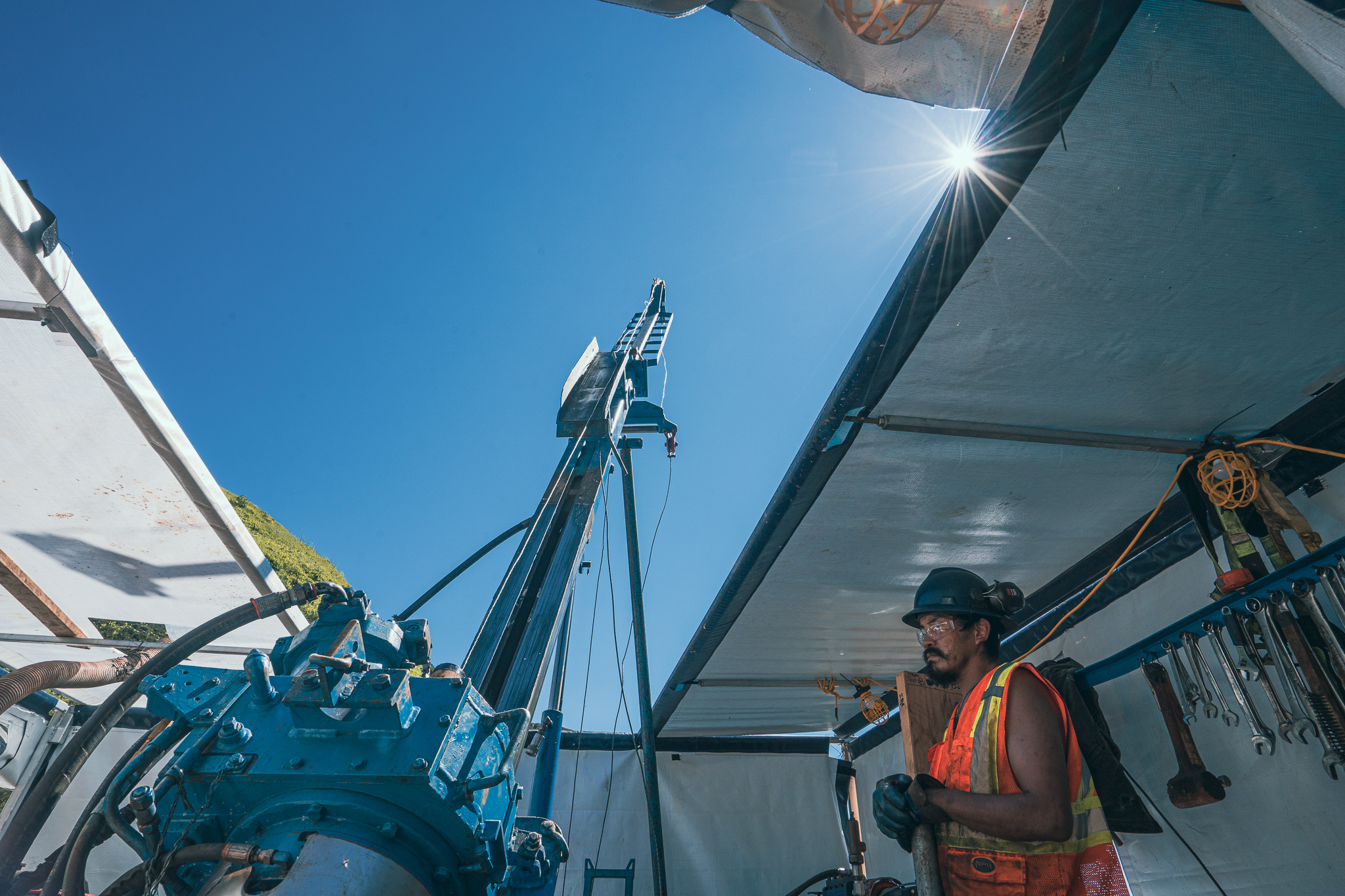

The Sudbury region is known worldwide for its massive mining operations, but rarely is there anything written or said about the “other” high-level technologies that are required to keep the mines in production and profitable.

Modern tunneling, boring and blasting techniques are always well documented, but when it comes to laboratories and testing, information is often scarce because many companies consider it to be “privileged and confidential” in nature.

One company, however, that doesn’t mind telling the world what it’s doing “in the labs,” so to speak, is Xstrata, because it is proud of the new process support plant it designed to process a wide range of ores for testing.

The Xstrata Process Support (XPS) plant crushes and screens up to 150 kg/hr (330 lb/hr) of ore, compared with about 100 kg/day (220 lb/day) for the company’s former manually operated facility.

“As far as we know, there is nothing else like it,” says an XPS Process Mineralogy Manager, Dominic Fragomeni. “The combination of mid-scale equipment and automated conveying and screening equipment increases productivity, improves safety by reducing repetitive strain and ensures test sample integrity and homogeneity.”

A new double-deck circular vibratory screen plays a key role in automating the flow of material through the facility by separating on-size crushed ore having maximum particle sizes down to 1.7 mm (10 mesh) from oversized fragments that require further processing. The screen disassembles rapidly for thorough cleaning, to prevent cross-contamination between batches.

Assessing the commercial viability of mineral deposits

The new crushing and blending plant is one of several lab-scale testwork units at XPS. The Sudbury facility also contains pilot equipment to test flotation, extraction and smelting strategies as well as scanning electron microscopes (QEMSCAN) and Electron Microprobe to analyze mineral compositions and modal mineralogy.

XPS once provided these services solely for its corporate parent, Xstrata Plc, but now operates as an independent subsidiary, providing technical services to the wider minerals processing industry.

Almost 50% of XPS projects are now external to Xstrata and this is growing.

The Process Mineralogy group evaluates samples from mineral discoveries to assess composition, physical properties, ore chemistry and response to extraction methods. This determines profit potential.

“For example, if 90 per cent of a deposit’s nickel is deported in the mineral pentlandite, it may be economically viable,” says Fragomeni, “but if significant amounts occur in pyrrhotite, it may not be viable because it is in a solid solution and therefore has little potential for upgrading into a concentrate.”

Although assays offer clues to processing strategies, every discovery has unique mineralogy. Before spending tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars on new extraction facilities, many companies are now testing ore samples at laboratory or on a pilot-plant scale to optimize their processes, and that’s where XPS Process Mineralogy’s new crushing and blending pilot plant provides the replicate sample charges for those tests.

Sample requirements range from 50 kg (110 lb) of material for laboratory testing to 10 metric tons (12 tons) or more for an extensive development program.

Mineralogy may vary significantly within a single mineral discovery. Geologists capture those differences by drilling for samples at different sites. XPS then crushes the drill core samples to a size determined by the testwork program, screens, blends and splits the material into homogenous samples that represent the mineralogy of the deposit or resource. This approach is also applied to distinct zones or variability samples within the resource.

Conveyors, Screening and Automated Material Movement

“In the past, most laboratories would produce samples manually. Someone would feed the ore into the crusher, then take the crushed ore in a pail and dump it into our original 102 cm (40 in.) diameter single deck screen. The fines would go into a pail and the oversize would go back into the crusher. We would keep going until all the material had been crushed down to the specified product size.

“Producing a 100 kg (220 lb) charge would take a worker a full day. One metric ton would require two full-time employees to work for two weeks. We then had to blend all of the screened material to ensure uniformity of each production run to ensure that all charges are homogenous,” says Fragomeni.

The automated line turns those days into hours, reducing the time needed to prepare a 200 kg (440 lb) sample from two days to 3-4 hrs, and producing multiple tons of samples in weeks rather than months.

The process begins with a remotely controlled platform that hoists pails of ore and dumps them into a hopper. The hopper feeds the ore into an 20 cm x 25 cm (8 in. x 10 in.) primary jaw crusher that handles ore fragments up to 15 cm (6 in.) in diameter.

Crushed ore is conveyed to the new 76 cm (30 in.) double-deck screener, a standard Vibroscreen® separator from Kason Corp., and sifted first by the upper deck. This large-aperture, heavy-duty upper “scalping” screen of stainless steel wire removes the largest, most abrasive fragments, thereby protecting the finer-mesh lower screen from damage while contributing significantly to the machine’s capacity. Material passing through the upper screen falls onto the lower screen, which removes all particles greater than the aperture size of any given screen installed.

XPS can change both screens to meet customer requirements. It typically uses a (4 mesh) upper scalping screen and a (10 mesh) lower cut screen. Some customers prefer different sizes.

“We work with one client who specifies a (3 mesh) cut screen and another who specifies a (6 mesh). We’ll do whatever the customer requires,” said Fragomeni.

Oversize particles exit both screens at their peripheries through discharge spouts and are transported back to the crusher for pulverizing, while on-size particles are loaded into drums awaiting blending.

Fabricated of 304 stainless steel, the screen is able to withstand constant vibration of abrasive particles. Vibration induced by a 746 kW imbalanced-weight gyratory motor mounted directly beneath the screening chamber promotes rapid passage of on-size particles through apertures in the screen, while moving oversize particles along a predefined path to the discharge chute at each screen’s periphery.

“The circular screen,” says Fragomeni, “handles as much as we can throw at it, and could probably handle the additional volume if we expanded the plant.”

A conveyor system receives the fines from the circular screen. A conveyor removes oversized material so it can be re-crushed, sifted, combined with the fines from the first screening and placed in drums. The drums are blended in one of two new high-efficiency, high-volume blenders capable of mixing multiple drums in a single operation, significantly reducing blending time when compared with the smaller blenders Xstrata operated in the past. Barrels of blended material are then discharged into two spinning rifflers, which divide the samples into smaller representative and replicate batches. The mixing and riffling process is so consistent, it produces test charges with relative standard deviations less than 2-5 per cent in their base metal content.

Cleanable equipment prevents cross-contamination

While screening performance is vital, so is cleanability. “We run one batch after another through the unit and we cannot tolerate any cross-contamination,” said Fragomeni.

XPS designed the plant so workers could clean it completely in three to four hours. The Kason screen is among the fastest machines to clean. According to Fragomeni, “You just undo a few clamps, take out the screen and vac

uum the top.This gives workers more time to spend on harder-to-clean equipment such as crushers and blenders.”

XPS was familiar with the screen before specifying the new 76 cm (30 in.) unit for its new plant. “We operated an older, 30 inch single deck vibrating screener in our bench-scale lab. It’s a standard product in mineral processing, but we needed a dual deck model for the automated crushing plant,” said Fragomeni.

“Our new facility is a break with the past. Because we have automated the crushing and sorting of minerals without sacrificing cleanability, our crushing plant is larger and faster, and we can produce large amounts of high-quality, replicate samples at competitive prices, which is often the most important part of a testwork program.”

Comments