Getting a handle on remote mine costs

It is becoming harder and harder to find the next mine. While the benefits of hunting for deposits in developed areas are clear, explorers are being forced to go into more difficult areas to find the next big discovery. Companies must understand that finding a deposit is just the beginning and that a thorough understanding of costs is essential. By developing cost models, an evaluator can determine where to best spend precious dollars and make the all-important go or no-go decisions.

In Canada, this means that companies are looking to develop new mines in the harsh conditions of the North.

Fortunately, Canada has a strong history of mining in the North from previous operations such as Cantung, Polaris, Pine Point and Faro to current producers such as Diavik, Meadowbank, Ekati and Minto, where building and operating mines in harsh conditions is just another day at the office.

To get a sense of what companies are working on, we searched the Mining Intelligence database to see which projects had reported moving beyond advanced exploration. Of the 111 Canadian developing projects in the database, 34 of them were located in remote areas which either have no infrastructure available or will require additional infrastructure.

The biggest hurdle that any new project has going forward is economic.

The figure below illustrates these projects by stage of development. Clearly, projects in remote locations are going to become more and more important as Canada develops new mines.

Evaluating the cost of building and operating mines in remote environments is critical to understanding the economics.

CostMine, a division of Mining Intelligence, has been evaluating projects and collecting data on supplies, equipment, labour and other key costs since 1983.

In this article, we wanted to see what difference location would make if all of the other parameters at a theoretical gold mine were the same. We used the same resources, grade, mining method, processing method and deposit type for each model. The only difference between the two models was location. By comparing the models, we could examine the differences between operating in a developed region where infrastructure is already in place, to operating in a remote region where roads, power, supplies and a local workforce do not exist.

The theoretical mine models in this article do not attempt to evaluate any current mine and are only used to illustrate the challenges.

Both models are open pit gold mines with an associated mill. They are assumed to be located in Ontario, one in a remote location and one with ready access to infrastructure. Our remote mine example will have a fly-in, fly-out camp, a winter generators and an airstrip. We have assumed that both mines will have the same operating parameters for the open pit mine and the mill.

All of the costs listed are in Canadian dollars, with the exception of the commodity prices which are in US dollars.

Gold Project – Open Pit Mine with Mill

For these models, we considered the differences between the cost of equipment, supplies, labour, power generation, infrastructure and capital required. We used our Mining Intelligence Evaluate software to calculate the capital and operating costs. The inputs for capital and operating costs were drawn from Mining Cost Service and the 2018 Canadian Mine Salaries, Wages and Benefits report, published by CostMine.

Items such as electric power can be three to four times higher at a remote mine versus a mine with access to a grid. Diesel fuel, explosives and lubricants can be 50% to 60% higher and labour can range from 20% to 40% higher at remote locations. In addition, camp and remote location facilities can increase the labour force by 15-25%.

In our models, we included all of the major equipment, supplies and labour costs common at this type of mine. To illustrate some of the differences, the table below lists some of our assumptions for a sample of key costs.

The cost of getting equipment, people and supplies to remote regions is, by far, the biggest challenge faced by miners.

In addition, the risks associated with changing markets for consumables cannot be understated. Cost estimates need to take into consideration changes in prices and market conditions and should be reviewed and revised as more information is available at each stage of the project. Just as resources are refined and improved, so should costs.

Below is a summary of the capital costs for both models. In our example, the remote mine model represents a 16% higher capital cost than the model in a developed area.

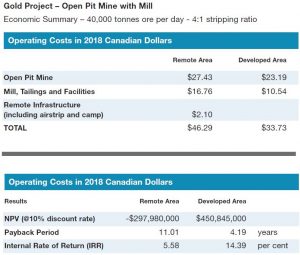

However, the real difference occurs at the operating cost level. As shown below, the operating costs at the remote example are 37% higher than a mine in a developed area.

Once we estimated the capital and operating costs for each scenario, we were able to calculate the net present value (NPV) at a 10% discount rate, payback

The table below illustrates the impact that operating in harsh conditions has on the economics of the project. In many cases, the economics could be improved by changing the mine design or method to improve grade or the processing technology to a different method to save both capital and operating costs.

In conclusion, the high cost of operating mines in remote areas of northern Canada has a direct impact on profitability simply based on location. Using economic modelling to understand these impacts will help explorers determine the minimum viability of a project. Cost estimating at the advanced exploration stage can help target the best projects, determine cut-off grade and assist in the overall strategy of obtaining financing.

In conclusion, the high cost of operating mines in remote areas of northern Canada has a direct impact on profitability simply based on location. Using economic modelling to understand these impacts will help explorers determine the minimum viability of a project. Cost estimating at the advanced exploration stage can help target the best projects, determine cut-off grade and assist in the overall strategy of obtaining financing.

Sam Blakely is a cost analyst and project geologist with CostMine, a division of Mining Intelligence (www.costs.infomine.com). He can be reached at sblakely@infomine.com. Jennifer Leinart is President of InfoMine USA, Inc., the CostMine division and a cost analyst. She can be reached at jleinart@infomine.com.

Comments